What price will a museum pay to hold onto a contested artwork? The Cleveland Museum of Art is facing this question following the seizure of one of its prized Roman antiquities.

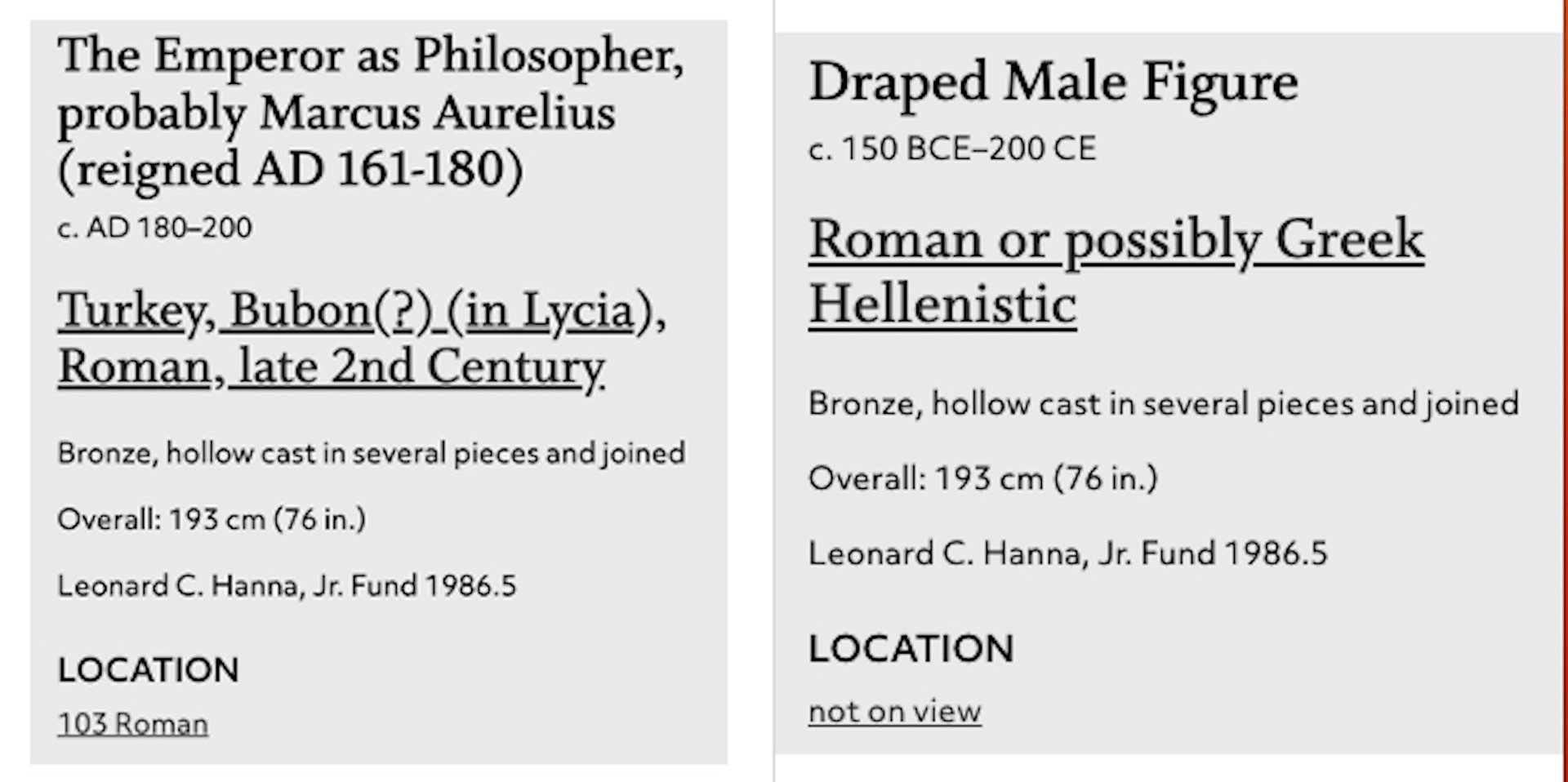

The work in question is a spectacular, life-sized, headless bronze statue of a man wearing a toga-like garment. Featured in every “greatest hits” guide to the museum, it presided until recently over the Roman sculpture gallery, despite previous claims by the republic of Turkey that it was looted. The label called it, “The Emperor as Philosopher, probably Marcus Aurelius (reigned AD 161-180),” and dated it to just after Marcus’ death, “c. AD 180-200.” The museum’s online listing for the statue repeated this information, adding that it came from “Turkey, Bubon(?) (in Lycia)”. But in recent months, the work’s origins and provenance have come under intensifying scrutiny.

First, law enforcement officials in both the United States and Turkey renewed their interest in artworks looted from Bubon. At this ancient site in southwest Turkey, local peasants discovered a number of bronze portrait statues in the 1960s. Despite strict cultural patrimony laws, they secretly sold the bronzes to antiquities traffickers. By the time Turkish authorities arrived on the scene in 1967, all that remained were empty pedestals and a single statue, now in a nearby museum. The pedestals bear the names of 14 Roman emperors and empresses, including Marcus Aurelius. Had it been scientifically excavated rather than plundered, the site—perhaps a shrine honouring the imperial family—would have been one of the most important archaeological discoveries of the 20th century.

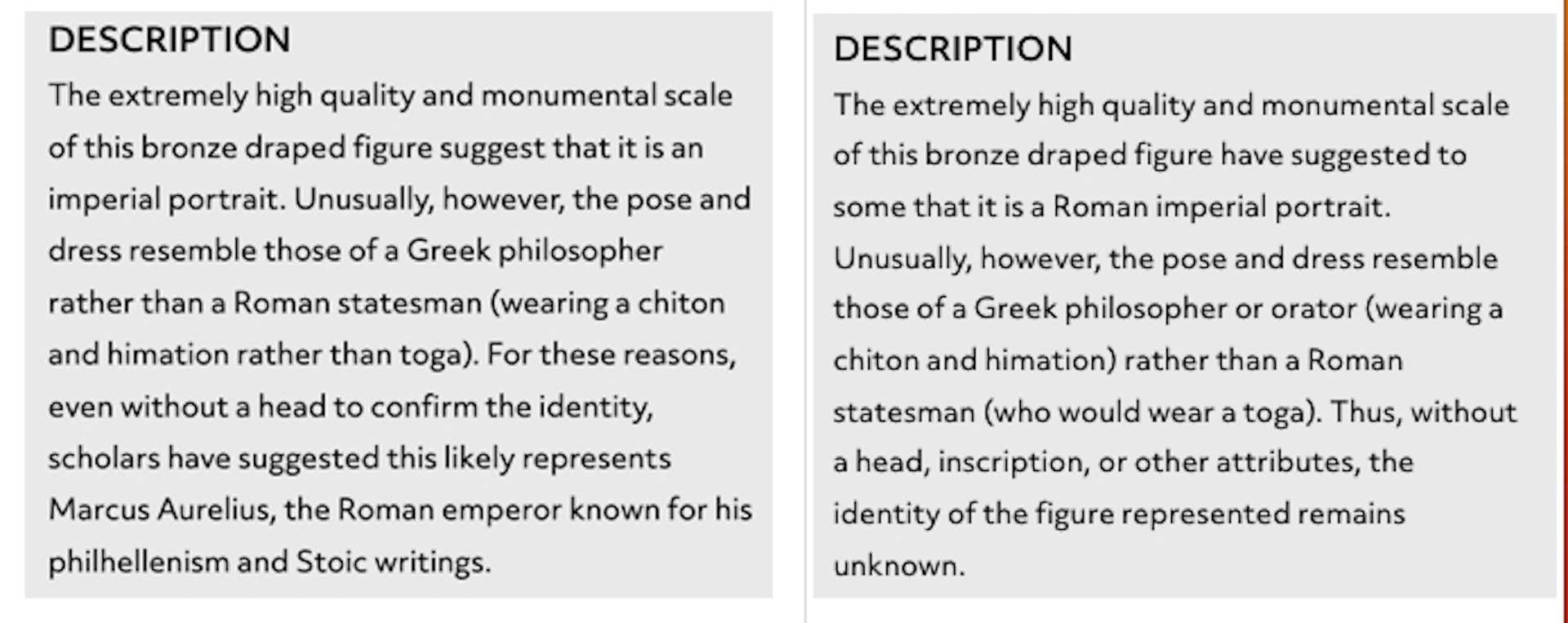

Information listed on the Cleveland Museum of Art website until recently (left) and currently (right) regarding the seized bronze Screenshots by the author

Unusual numbers of high-quality Roman imperial statues and portrait heads began appearing on the international art market in the mid-1960s. Dealers whispered the story of these extremely rare bronzes’ discovery in southwest Turkey. Between the 1970s and 90s, Turkish and American scholars attempted to reconstruct the dispersed Bubon group. Recently, the Antiquities Trafficking Unit of the Manhattan District Attorney’s office, in partnership with Turkish authorities, renewed the investigation, building on that earlier work. Since November 2022, four other Bubon bronzes have been seized from public and private American collections, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Fordham Museum of Greek, Etruscan and Roman Art. These are being returned to Turkey.

Last spring, Cleveland’s statue of Marcus Aurelius was taken off view. The museum purchased this work in 1986 from the same dealer, Charles Lipson, who sold three of the four pieces that were recently seized. It, too, has always been associated with Bubon. Indeed, for the statue’s 1987 debut, the museum displayed photographs of other Bubon statues and an additional Bubon portrait, borrowed from another museum. The gallery labels and press release discussed the group as a whole and its likely origins at a provincial shrine in Turkey honouring the Roman imperial family. The museum’s curator even travelled to Bubon and published a scholarly article examining this context.

Descriptions of the seized bronze on the Cleveland Museum of Art website until recently (left) and currently (right) Screenshots by the author

The most recent developments, however, negate that context. Not only did the museum remove the statue from view and the Manhattan District Attorney issue a warrant for its seizure; the statue’s online listing has been rewritten. The references to Bubon, to Turkey and even to Marcus Aurelius have been deleted. It is now simply called a “Draped Male Figure”. There is no information about where it came from. Its hypothesised date is no longer the period after Marcus’s death. Instead, the museum throws up its hands, claiming it could have been made at any point over a 350-year span, between “150 BCE and 200 CE”. It could be “Roman or possibly Greek Hellenistic”. Although the museum has not removed an embedded video titled “Imperial Portrait?” that discusses Marcus Aurelius, this more specific information is directly contradicted by the new written description of the statue, which states that, “Without a head, inscription or other attributes, the identity of the figure represented remains unknown.” In fact, an inscription to Marcus Aurelius at Bubon has been known since 1993.

It is clear that these erasures are a defensive response by the museum to moves by the Manhattan District Attorney. The museum’s chosen strategy is to pretend to have no idea what this statue is, despite decades of scholarship and public education to the contrary. In doing so, it is tacitly admitting that it would rather erase knowledge about a major work of ancient art than have to return it to the country from which it was stolen. This stance represents a serious compromise of the museum’s ethics and integrity, and is certain to erode public trust. This is a devil’s bargain indeed.

The Cleveland Museum of Art’s response

“The Cleveland Museum of Art takes provenance issues very seriously and reviews claims to objects in the collection carefully and responsibly. As a matter of policy, the CMA does not discuss publicly whether a claim has been made. The CMA believes that public discussion before a resolution is reached detracts from the free and open dialogue between the relevant parties that leads to the best result for all concerned.”

- Elizabeth Marlowe is a professor of art history and museum studies at Colgate University