The so-called “Great Wealth Transfer” from the baby boomer generation is increasingly visible on the art market, but will there always be demand to match their post-war taste?

At the latest count, by the research firm Cerulli Associates, Americans can expect to inherit $73 trillion over the next 25 years, with 42% of the transfers to come from the wealthiest 1.5% of households. These own the most stocks, property and—it is safe to assume—art. Individual collections have bolstered the art market in the past few years, many from owners who have recently died. From last month's mammoth New York sales came 16 works from the collection of the media heir S.I. Newhouse, estimated at more than $144m; 220 works valued at $270m-plus, from the collector Gerald Fineberg; $40m from Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen—who boosted last year’s auction results by $1.6bn—and 33 works estimated at $120m from the record producer Mo Ostin.

Much like an ageing collector, the air is getting thinner on top

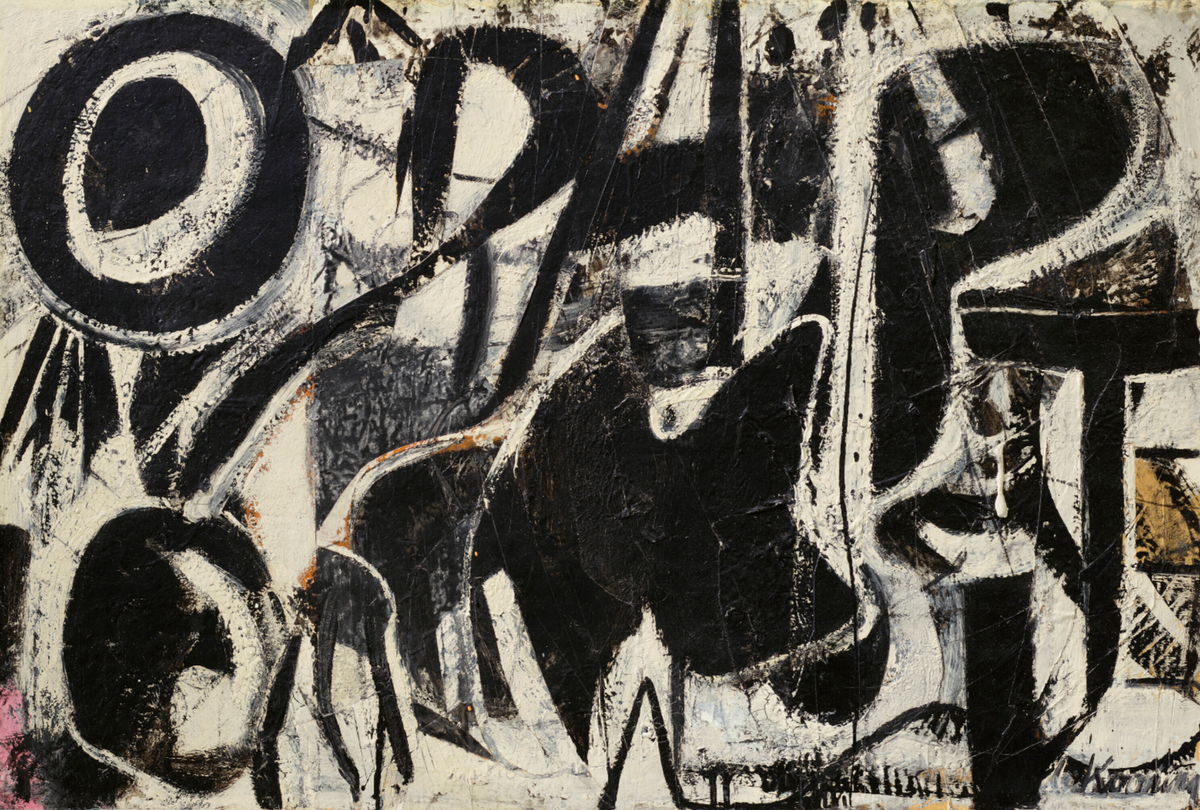

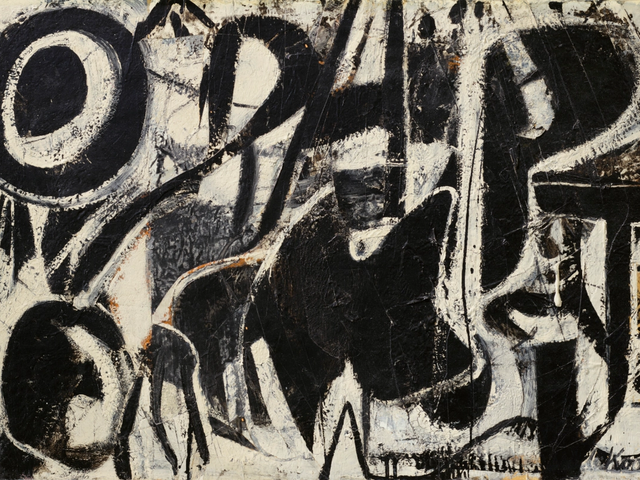

Many of the highlights come courtesy of 20th-century grandees we have seen a lot of recently: think Willem de Kooning, Picasso, Gerhard Richter and René Magritte. So far, so good. We have come to learn that art is a supply-driven market that seems to defy economic logic. In the multi-million zone, collectors will keep buying those “important” works with fulsome estimates, whatever the backdrop.

But, much like an ageing collector, the air is getting thinner on top. One concern, which the advisory business Cadell is flagging to clients, is that just as the boomer generation dies out, so does its taste. A recent report by Sotheby’s and ArtTactic finds that boomers (born between 1946 and 1964) accounted for 40% of bids on $1m-plus art in 2022, down from 48% in 2018. Cadell says that if this trend continues, the numbers would halve again over the next 10 years.

Change of taste tack

Younger collectors are a growing proportion in the $1m-plus zone, and their inheritances will keep rolling in, but the question is what will they want to buy? One reason for selling the art in the first place is that collectors’ children and grandchildren think differently to the preceding generations. An example that stood out from the latest Art Basel and UBS report is that dealers’ share of sales of video art, for long a stubbornly slow market, grew substantially last year—from 1% to 5%. The market is unlikely to shake off its love of paintings any time soon, but a change of tack is plausible as the definition of art keeps expanding. It isn’t so long ago that Old Masters were the top of the taste tree.

A shift is already underway—art by dead, white men feels increasingly irrelevant and unwanted. The auction houses are at pains to show the diversity in their collections on the block this month, notably Fineberg’s, but it’s an uphill battle given the pool of work available. At some point there won’t be enough 20th-century women or artists of colour to bridge the gap. In the meantime, expect more and more boomer collections to come onto the market, before the air gets even thinner.