You’re waiting for an Uber. Maybe you’re leaving a dinner in Basel or a party on Miami Beach.

The app spins ... it is “looking".

Finally: "12 mins".

"12 mins"?

Like China’s social credit system, Uber takes into account vast amounts of data when matching a rider with a driver. The algorithm isn’t public but just knowing everything Uber knows about us, it’s not unlikely there is both a public and private rider score that impacts rider experience.

What if the art world worked the same way? Are you sure it doesn't?

While the art world is a world of big money—$65.1 billion according to the 2022 Art Basel and UBS Global Art Market Report—at its heart it is a reputation economy. There are blacklists in service of protecting artists and blacklists in service of petty feuds. There is imperfect and asymmetric information regarding which galleries, collectors, and artists don’t follow through on payments. There are “open secrets". There are many rumours. Technology is changing both how the art world takes account and how it is held accountable. Here are three trends and technologies to keep an eye on.

1) Ghost collectors & glass doors

Ghosting, which has been made popular by dating apps, describes the practice of ending all communication and contact with another person without any apparent warning or justification and ignoring any subsequent attempts to communicate. According to the Harvard Business Review, ghosting in professional contexts is on the rise in other industries as well. The spineless behaviour can seem more or less safe in a world where data is not centralised but galleries, institutions, and even artists are now using database software like Art Logic and the less art-centric HubSpot that keep track of customer information, artwork databases, digital marketing return on investment (ROI), and sales processes.

What Uber has that the art world lacks is a near monopoly creating a centralised data collection that is fully owned. As the art world gets more technical we can expect that better systems will be in place with the potential to understand trends. What should an artist or employee do when they aren’t paid by a gallery? Glassdoor is a website where current and former employees anonymously review companies. Many major galleries are on it, with ratings and reviews for management that give a less-than-friendly portrait that will be unlikely to dissuade collectors but might convince entry-level employees the cachet isn't worth it.

2) Crypto

Cryptocurrency is being used to pay for physical artwork as well as NFTs. In a previous article, I mentioned how the UAE’s tax-free capital gains has helped make it home to many crypto collectors. More than a year ago the Dubai-based gallery Galloire became the region’s first gallery to be able legally to accept crypto as payment. According to the founder Edward Gallagher, “Part of the core of Galloire as a gallery and art platform is to break down the barriers between digital and physical: In the sense of art mediums yes, but in every way, including how we can see art and exhibitions, but also how one can pay for art.” At first I was sceptical that it would be embraced. Transacting the crypto exposes galleries and artists to the huge exchange fluctuations. But it turns out that 20% of purchases at the gallery are occurring in crypto instead of fiat currency. The gallery understands the risks but sees it as an important part of welcoming new collectors, “We want the art collector audience to grow and so we want people to acquire art however they want,” Gallagher says. Other technologies that limit the operational drama involved in paying and getting paid are Stripe, Square, and the foreign exchange-friendly bank Revolut.

3) Arcual

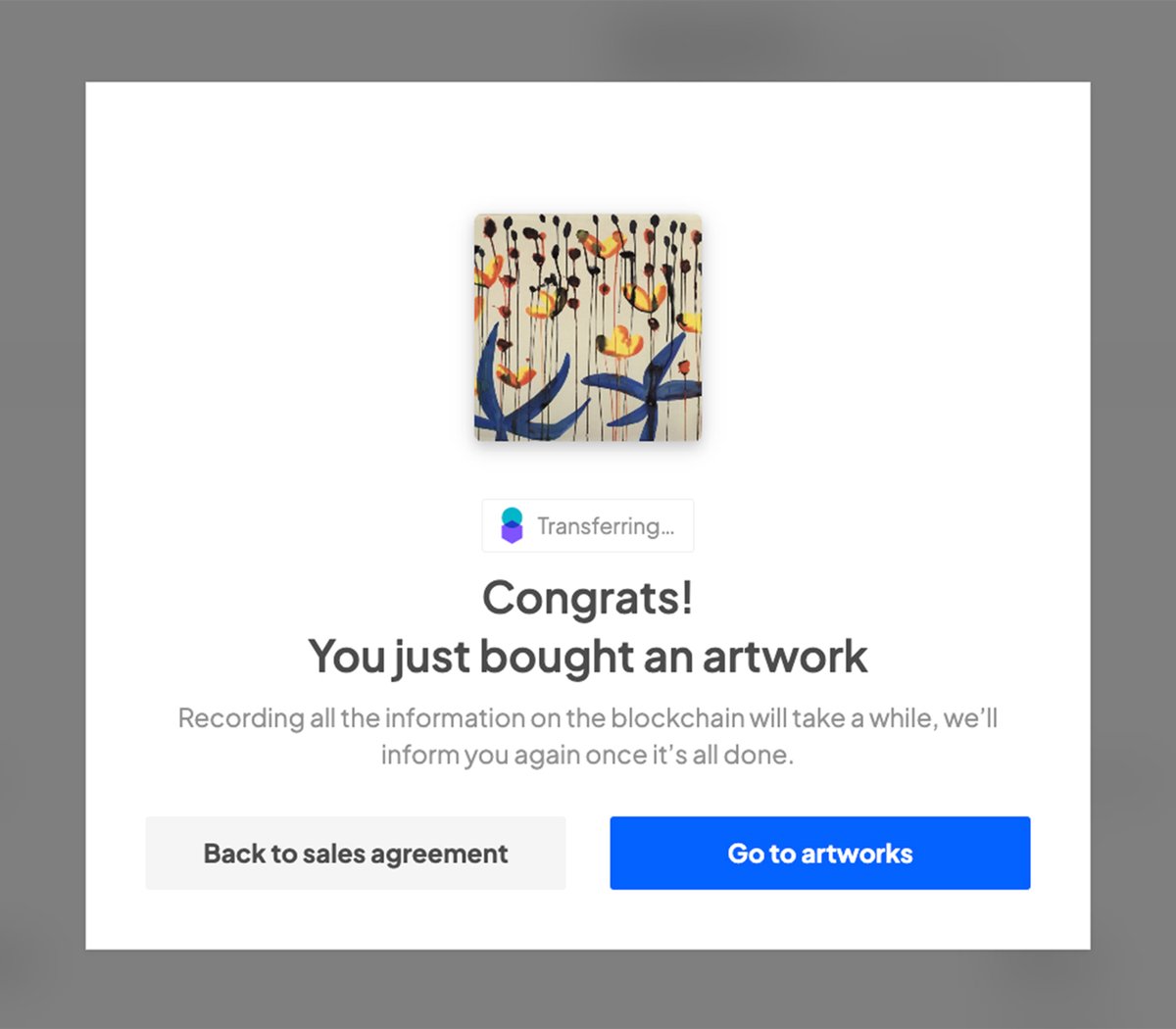

When there is structure and reliable technology and systems in some parts of the art world it allows for more freedom, creativity, and humanity in others. One interesting emerging solution is Arcual, a system that supports royalty-sharing, efficient payments, and digital records of authenticity. Launched at Art Basel in Miami Beach last year, it has serious art-world backers with the LUMA Foundation and MCH Group, the parent company of Art Basel. The software uses blockchain technology, but not crypto, to remove drama and transaction time from payment collection and dispersal. At the moment galleries are invited by the platform and initiate consignment agreements for artworks that need to be approved by the artist. The agreement is registered on Arcual’s permissioned blockchain which has a focus on data privacy, and that information remains private between the gallery and the artist. When the gallery sells a work, the collector approves a sales agreement allowing them to proceed with payment via debit, credit card or bank transfer payments in the agreed currency. Once the collector has successfully paid the sales agreement the artwork’s new ownership is put in the official, unchangeable record. The gallery and the artist are both paid out simultaneously according to terms they had both when they created the consignment agreement. The platform suggests other future possibilities from normalised resale royalties to more complicated revenue splits from artwork sales.