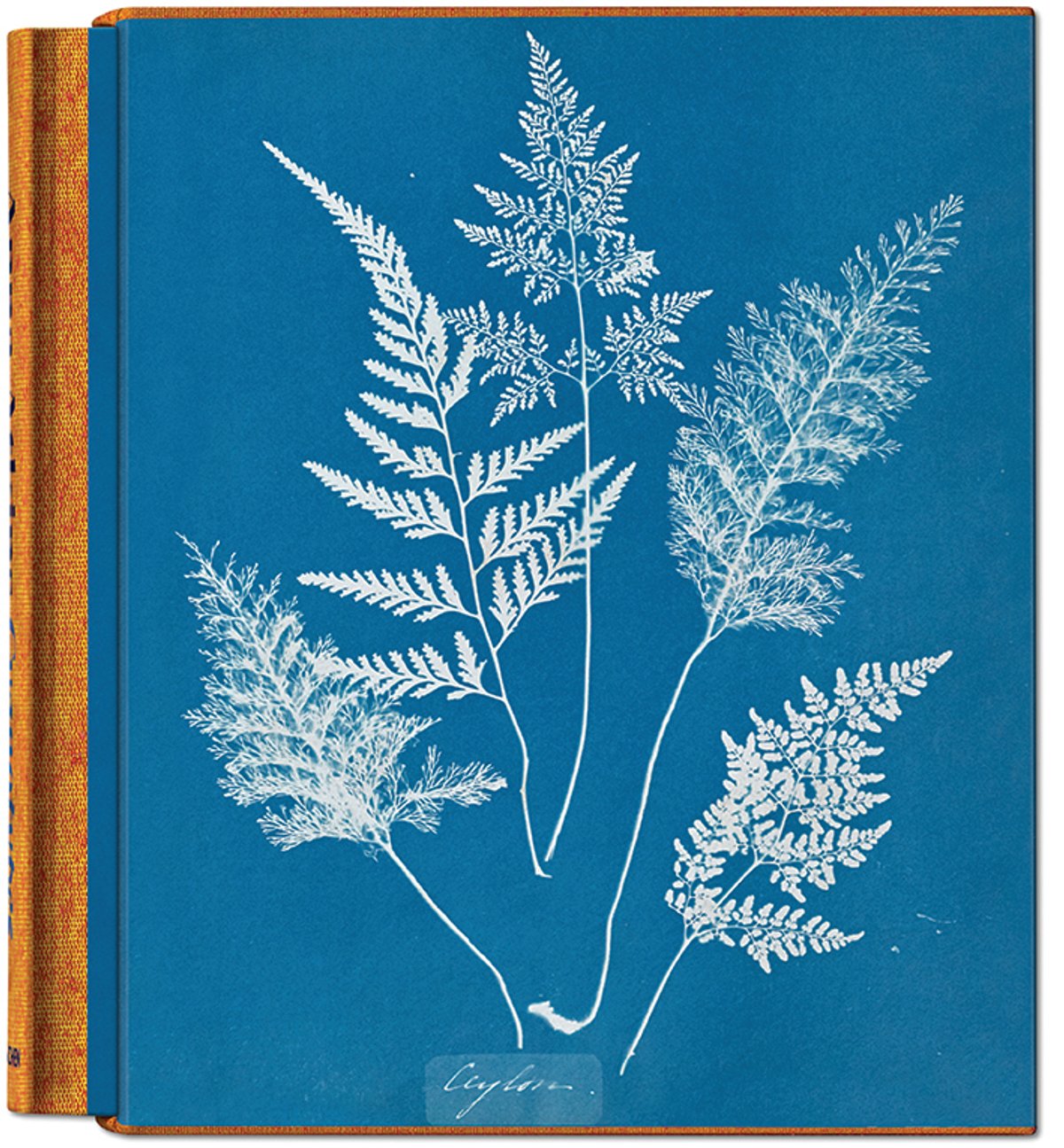

British Algae (1843-53) by Anna Atkins is thought to be the first book to be illustrated using photographic images. The English botanist (1799-1871) produced her collection using the cyanotype technique, which she became aware of through her father’s friendship with its inventor, John Herschel. Later this month, Taschen is publishing a facsimile of British Algae alongside Atkins’s other book, Cyanotypes of British and Foreign Ferns (1853). Below is an extract from an accompanying essay by Peter Walther, detailing Atkins’s development of the book.

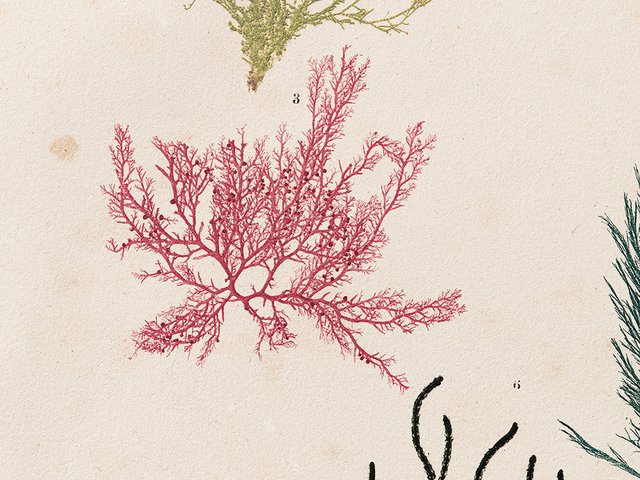

Anna Atkins herself had collected and dried most of the plants included in British Algae. At harvest time, the algae were immediately rinsed in water, then taken home where she used dissecting forceps and camelhair brushes to remove extraneous matter, before finally pressing and drying them. Since the backs of many of Atkins’ images are pale blue in colour, we can assume that she did not always sensitize the paper with a brush or sponge. Instead, she immersed it in chemical solutions. To create a cyanotype, Atkins placed the plants on to the suitably prepared paper set into a copy frame, which she then covered with a glass plate so as to guarantee the closest possible contact with the support surface. The result was a lavishly detailed outline image. Areas only partly permeable to light appeared brighter in the image than those fully exposed, while denser algae were less distinctly visible.

Alongside the specimen, a label showing the name of the plant was placed on the paper. The label indicating the plant’s name was first dipped in oil to make it transparent, so that when exposed to the light only the script remained.

Depending on the weather and the intensity of the sun the copy frames were left [...] for between five and 15 minutes. After a time, the paper would turn to a yellowish green colour which, after the sheets were rinsed in water, turned to a more or less intense blue.

Delesseria sinuosa from Atkins's British Algae, Part V (1845) © TASCHEN / New York Public Library

Anna Atkins gave her cyanotypes serial numbers. Even when she examined the plant numerous times, there were some noticeable differences between specimens belonging to the same series. Before each exposure, the algae were rearranged on the prepared paper. Sometimes they appeared in reverse in the image, but at other times they seemed to have moved only a short distance. The intensity of the blue varied from one species to another. October 1843 saw the publication of around 15 copies of the first volume of British Algae, which she dedicated to her father. In a foreword, Atkins reflected on the reasons why she had produced the book. “The difficulty of making accurate drawings, so minute as many of the Algae and Confervae, has induced me to avail myself of Sir John Herschel’s beautiful process of the Cyanotype, to obtain impressions of the plants themselves, which I have much pleasure in offering to my botanical friends.”

The first editions of the album were sent to the Royal Society, Herschel, [Henry Fox] Talbot, the minerology and photo pioneer Robert Hunt and the book collector Thomas Phillips. The British Museum, the Linnean Society of London and the botanical gardens in London and Edinburgh were similarly honoured. [...] In the subsequent years leading up to the spring of 1849, a total of ten volumes, each containing twelve prints, [were sewn] together by hand. The recipients were responsible for collating and binding the sections together.

• Anna Atkins: Cyanotypes, Peter Walther, Taschen, 660pp, £100 (hb)