A film about the life of British documentary photographer Patricia ‘Tish’ Murtha is due to open the film festival Sheffield DocFest on 14 June.

The film, titled Tish and directed by Paul Sng, is a celebration of “a working class artist whose work was tragically overlooked while she was alive,” says Annabel Grundy, Sheffield DocFest’s managing director, in a statement.

Murtha died in hospital after suddenly falling ill at home in South Shields in 2013. Today, she is recognised as one of the most significant photographers of her generation.

But the conditions of Murtha’s life counted against her, conspiring to ensure she was never given the recognition her work deserved. "She was an outsider in the art world,” Sng tells The Art Newspaper.

“Back then, the arts were dominated by middle-class people, as they still are now,” Sng says. “Tish didn't choose to be an unknown artist, but she was not supported by gatekeepers in the photography world.”

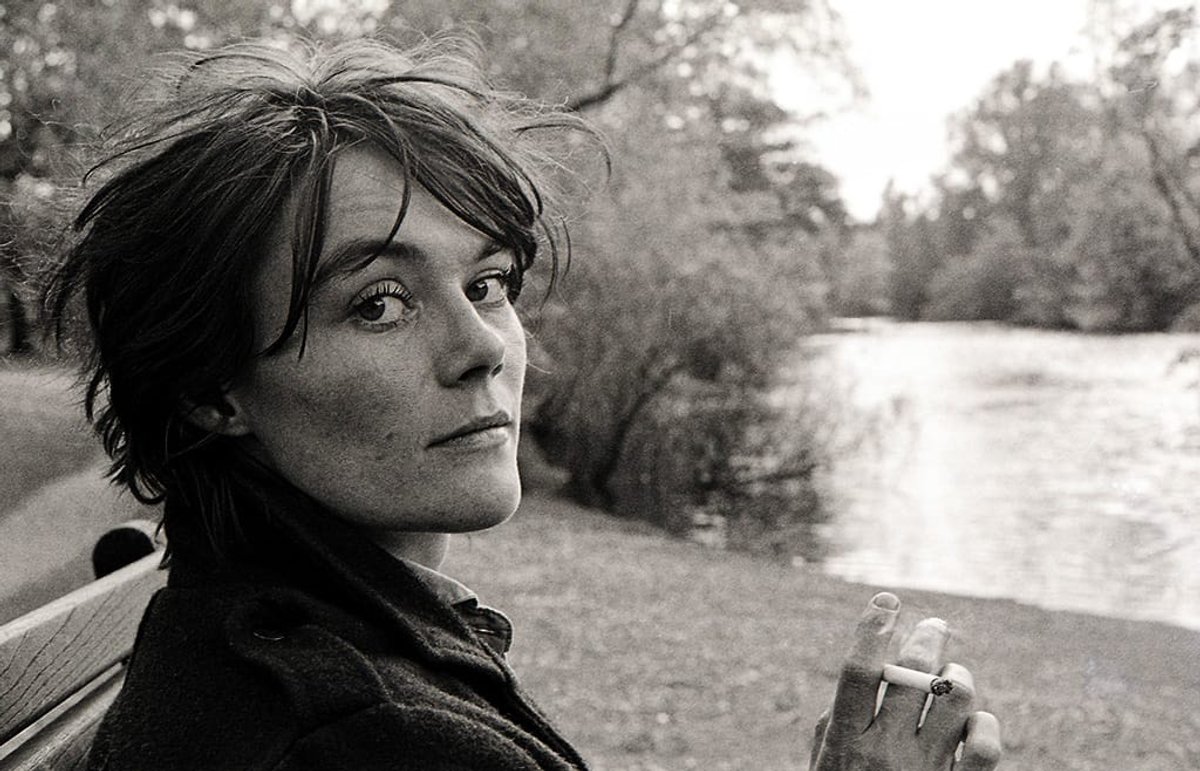

© Tish Murtha, courtesy Ella Murtha

Those gatekeepers missed out on a unique artist. “She had a female gaze, and she represented women as having agency,” Sng says. “You didn’t see this in the work of some of her male peers.”

Murtha was born in 1956, one of ten siblings, in the northern coastal town of South Shields. Her family then moved to Elswick, a deprived part of Newcastle. Murtha spent time in care during her childhood. Her early photography is testament to the kind of poverty she had to overcome.

Her career began in 1976, when she took a short course in photography at Bath Lane College of Art in Newcastle at age 20. Her lecturer, Mick Henry, convinced Murtha to apply to the Documentary Photography course in Newport, Wales, run by the Magnum photographer David Hurn. It was, at the time, the only recognised full-time photography course in the UK. Murtha could not afford it, so Henry managed to secure a grant from the local council to support her studies.

In Wales, Hurn helped Murtha hone her prodigal talent—her first unified series, Newport Pub, comprised images taken from inside the smoke-filled boozers of Newport, the result of hours upon hours of close observation and careful engagement.

"She was the perfect student," says Hurn in an interview with The Art Newspaper. "She absorbed everything we said. She was passionate. She was really exceptional."

Hurn, himself one of the UK's most respected photographers, quickly realised Murtha's talent. "She quickly befriended an elderly couple on the street she lived on in Newport," Hurn remembers. "She presented a very tender, very beautiful series of portraits of them. I loved them. I realised I would never be able to make photos like that."

Hurn became a mentor; he agreed to be Murtha’s guarantor so she was able to buy an Olympus OM-1 camera on credit. She paid for the camera in instalments by working in a nightclub. Almost all of her work was created with it.

"She clearly had very little money, and so would work all hours of the evening to get by," Hurn says. "But she was always hard at work on her photography during the day. She would always be on time. She was staggeringly hard-working."

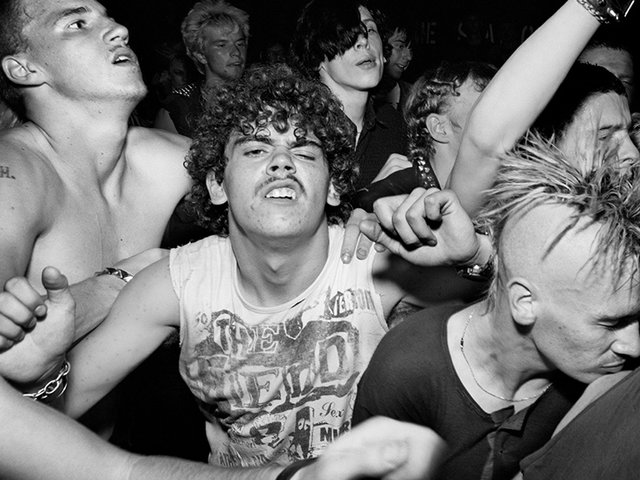

© Tish Murtha, courtesy Ella Murtha

After graduating, Murtha briefly moved back to Newcastle. There, she created the two bodies of work she is perhaps best known for today. Elswick Kids, a documentary series of children at play on the streets she grew up in, was itself an implicit mediation of her own childhood.Youth Unemployment, meanwhile, was an explicitly political series about the generation of people who, she felt, were denied the chance to make a living for themselves under Margaret Thatcher’s government.

Simon Bainbridge, the head of content for Magnum Photo Agency, says Murtha approached her subjects on a level of mutual understanding.

"Looking at her pictures now, the poverty is shocking," Bainbridge says in an interview. "These kids had very little in material terms. But they had an imaginary life, which played out on the streets with their friends. Murtha saw that. And she saw their lives as worth recording—in part, because she was looking from the inside."

The work led to Murtha being employed as a community photographer by Side Gallery, the Newcastle photography gallery which opened in 1968 and closed this month due to lack of funding.

In the early 1980s, Murtha decided to move to London, perhaps realising she needed to be closer to the established photography industry if she were to turn image-making into a career. There, she began to collaborate with the ageing master Bill Brandt, who was himself once a student of Man Ray and was regarded as one of the most revered photographers of the century. Together, Brandt and Murtha worked on London By Night—a portraiture-based series commissioned by The Photography’s Gallery in Soho and exploring, with rare empathy, the experiences of women working in sex work in the nearby streets.

The series was made possible through Murtha’s friendship with Karen Leslie, a Canadian woman who worked as a dancer in a Soho club. The pair lived together in a flat in Russell Square and, through Leslie, Murtha was able to meet women who worked in Soho’s sex industry, many of whom became her friends.

“Tish's approach was collaborative; she made work with people, not merely about them,” Sng says. “In London By Night, she avoided a voyeuristic lens by earning the trust of the people she photographed.”

The series received acclaim, undoubtably in part because Brandt’s name was attached to it. He died less than a year later, in 1983. Murtha, for a brief time, was considered an heir apparent; the next new voice in British documentary photography. Although, all the while, she would often admit that she found the photography scene difficult to navigate; cold, insular and political.

© Tish Murtha, courtesy Ella Murtha

“Tish was a working class woman, so she was not afforded the same opportunities as some of her contemporaries,” Sng says. “She came up against systemic barriers, but she also had a stubborn streak. She refused to compromise her principles and values in order to achieve success.”

But Hurn is rather more pointed. "Unfortunately, whenever she worked on something, she had a habit of falling out with people," he says. "I think she would have got further on in her career if she got over her inability to get on with people."

Shortly after London By Night, Murtha became pregnant, giving birth to Ella in 1984. Without a financial cushion behind her, and facing an art world insensitive to the demands that motherhood places on jobbing photographers, Murtha found her opportunities dwindle. She tried to make London work, doing commercial photography mostly for Edward Arnold Publishers. But the tragic death of her friend Karen Leslie, a victim of a hit-and-run while riding a bicycle through the streets of London, brought the chapter to a close and, in 1987, Murtha decided to return with Ella to the North East.

Murtha died on 13 March 2013, the day before turning 57, from a brain aneurysm. She died having never published a photobook in her lifetime, while her work had only been exhibited on a handful of occasions. Her work never gained as much recognition as London By Night, which she had created at the age of 27.

Tish Murtha's daughter Ella

Photo: Tish Murtha courtesy Shef DocFest/Paul Sng

Her daughter Ella, who was 28 at the time of her mother’s death, was left to put her affairs in order. Sorting through her possessions, Ella realised she was now in the possession of thousands of negatives and photographs, many of which had never been seen or organised.

The film on show at DocFest is testament to Ella’s determination to establish her mother’s legacy in the British documentary canon. Ella and Paul Sng raised funds for the film via a crowdfunding platform, making more than £45,000 from more than 850 small donations.

The film will speak to a lot of young people who aspire to be artists but worry for their future prospects, Sng says. “Funding opportunities are becoming even scarcer," he says. "People from privileged backgrounds don't face anywhere near the same challenges as working class people, who generally aren't able to dip into bank savings or borrow money from their parents to keep going. That’s a widespread concern across the arts.”

In life, Murtha felt rejected by photography. But, a decade after her death, it is clear her photography still has the capacity to speak to generation after generation of working class artists.