This month, Tate Britain will open an exhibition of the work of the photographer Don McCullin. It is a significant moment in British museums’ collecting and display of photography, because McCullin is the first living British photographer to have a career survey at any of the Tates. This year also marks the 10th anniversary of the Tate’s appointment of its first ever curator of photography—Simon Baker, who left last year, after nine years at the Tate, to become director of the Maison Européene de la Photographie in Paris.

Under Baker, leading British photographers such as McCullin and Chris Killip, who had been ignored until then by the Tate, were finally embraced by the UK’s national collection of British and international art. They had been represented in British public collections for some time, though: the Victoria and Albert Museum, which is the “national collection of the art of photography”, has more than 100 works by McCullin.

Don McCullin’s 1961 photograph Near Checkpoint Charlie, Berlin, taken at the height of the Cold War © McCullin

The Tate show symbolises a shift in photography’s significance in British museums, and not just because the Tate is correcting its historic disregard. Last year, the V&A opened phase one of its Photography Centre, an expanded permanent space for photography. Despite collecting photography since its earliest years in the mid-19th century, the museum had waited until 1998 before assigning it a dedicated space. There are vast photographic collections at the Imperial War Museums in London and Manchester, and at the National Portrait Gallery (NPG). At the NPG, in particular, there has been an increasing volume of (often extremely popular) photography exhibitions over the past decade.

A complex history lies behind photography’s now exalted status in British museums. Martin Barnes, the senior curator of photographs at the V&A for the past 22 years, says that the 1970s and 1980s were a fertile period both for the independent photography galleries as well as museums and libraries taking “a huge look back at photography’s own history and its own position”.

Arguably the most important catalyst in terms of the professional world around photography was the 1980s and particularly the 1990s, when, Barnes says, “photography got big, in a physically larger scale, and colour printing quality became much better”. Photographers were able to make photographs “that competed in scale with the new art museum building, the big personality art museums that were being constructed in that period, as well”, he says. It became “an interlinked catalyst-circuit, between the collectors, the market and the big new museum buildings, increasing the consciousness of photography’s history.”

The Tate had acquired photographic works before this point, but only very sporadically: Cindy Sherman’s photographs had begun to be collected in 1983, for instance. “Tate had obviously been both showing and collecting photography, but primarily photography that was connected with conceptual art practice, like John Baldessari or Richard Long or Hamish Fulton,” Baker told me in a 2012 interview. “The old Tate line from the 1980s was that Tate collected photographs by artists… but it didn’t collect art by photographers.”

The V&A opened the Photography Centre expanding its permanent space for photographs Courtesy of V&A

The V&A was continuing to acquire photography across the spectrum of the practice, but from the mid-1990s the Tate made a significant effort to acquire work by artists in the Düsseldorf School. It could hardly ignore them, as they were among the key artists at the heart of the boom in large-scale colour photography. Works acquired include images by Thomas Struth and Andreas Gursky, including Gursky’s Rhein II, which has since become the most expensive photograph at auction: an edition sold for $4.3m in 2011.

Still, before Baker joined, the Tate had drawn a line between these artists and photographers such as McCullin and Killip. “The decision to change was really to reflect the fact that it is really impossible to keep the kind of distinctions that had been operating between one kind of photography and another,” Baker said in that earlier interview. “That distinction is just impossible to maintain now, the way that photography is changing and contemporary art is changing. So the decision was made to collect photography fully, in as many forms and ways as possible.”

The collapse of the distinction between “art photography” and other forms is starkly illustrated by McCullin’s presence both in the Tate collection, which has 85 of his works as part of its Artist Rooms series with the National Galleries of Scotland, and the Tate Britain exhibition. Baker argues that McCullin fits easily into the canon of image making in Britain. “If you talk to him about why he photographed homelessness in London, he will very quickly talk about Hogarth and Gin Lane,” Baker says. “If you talk to him about landscape photography, he will talk to you about landscape painters he likes, and the whole tradition of landscape and the British landscape.”

Paul Strand, Young Woman and Boy (1932) ©Aperture Foundation Inc., Paul Strand Archive

Still, there is a distinction, in market terms at least, between artists better known for their work as reportage and those who have long been shown in art museums. Baker recalls an anecdote from Grayson Perry’s Reith Lectures for the BBC in 2013: “I asked Martin Parr, the very famous and brilliant photographer, if he could give me a kind of definition of… an art photo as opposed to another sort of photo,” Perry recalled. “And almost in jest, he said: ‘Well if it’s bigger than two metres and it’s priced higher than five figures.’”

Parr has a point. The auction record for Struth is $1.81m, and for Wolfgang Tillmans £605,000; for McCullin, it is £18,750. Baker says artists such as Struth and Tillmans “normalised the idea of liking the photographic image, for many museum visitors and probably also for curators and collectors, so they were able to appreciate photography a little more”. He adds: “Many photographers will find someone like Wolfgang Tillmans very challenging because they won’t understand why people find his work so much more valuable in monetary terms when it’s so anecdotal and everyday. But for sure, Wolfgang’s work has opened up the possibilities for many other artists to be visible and to be present, and I think that’s to everyone’s benefit.”

At the V&A, all forms of photography have long had a level playing field. Barnes says that with the Photography Centre project, he “wanted to go back to the basic principles of what works in the museum, which is: here is photography, it’s a materials and techniques gallery, and let’s explore how photography is made, who makes it, what it’s used for in all of its different forms”. The accessibility of photography, especially in the digital era, is crucial, making it increasingly possible “to understand how you might make a photograph”, where there is no equivalent understanding of making a painting or a tapestry.

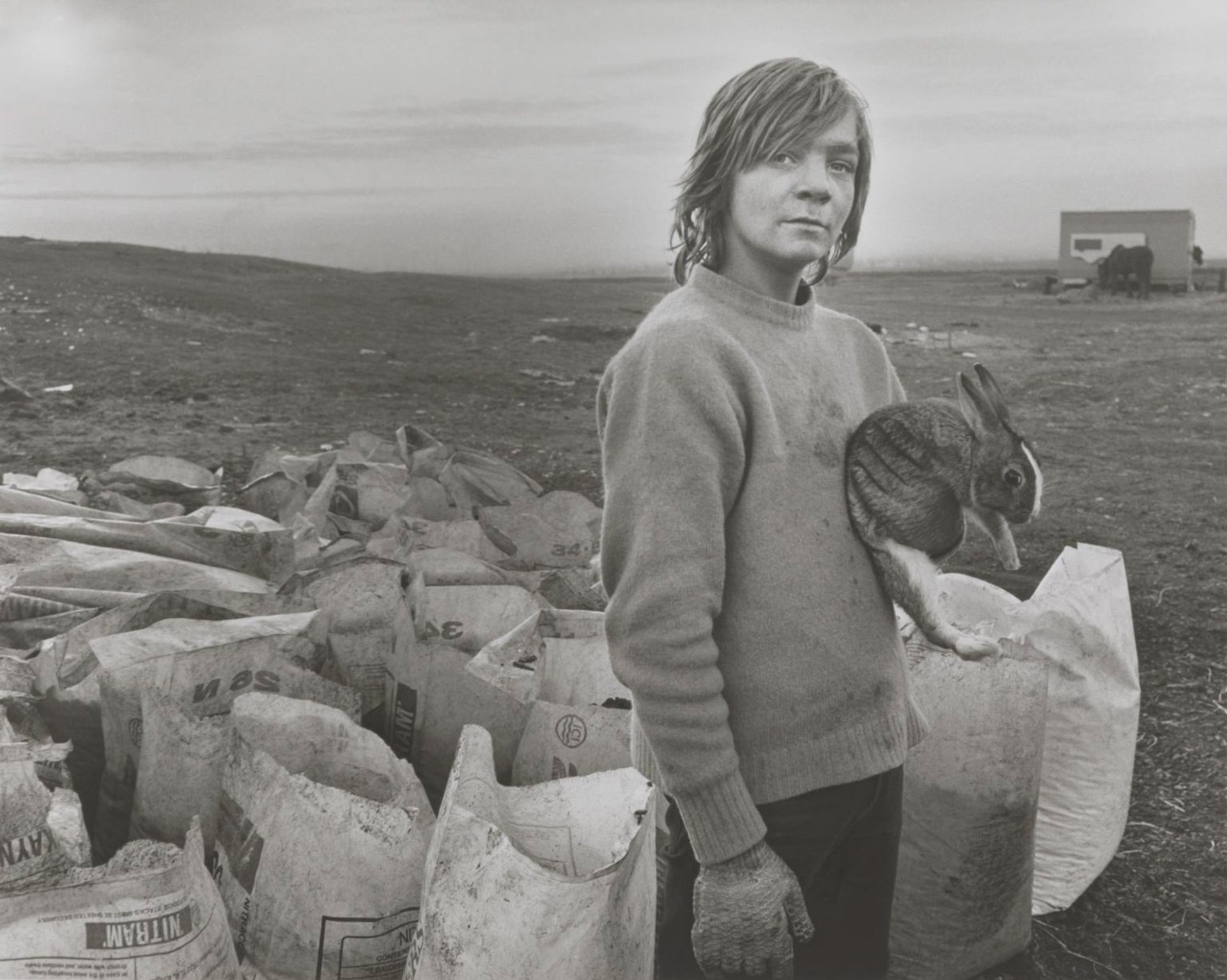

Chris Killip, Boo and his Rabbit (1984) © Chris Killip/Tate

Barnes is trying to “unpack a long history of photography, where it might help the public to understand where it came from”. For this reason he says, he would redraw the description of the V&A’s holdings as the national collection of “the cultures of photography” rather than the art of photography. “Because how it’s used and applied consciously by creative individuals is mainly what I’m interested in, in photography. But that doesn’t necessarily mean that it’s just art.”

“Just art” is the Tate’s remit, of course, so it has worked together with the V&A. “Simon [Baker] and I met often, and the Tate approach to collecting photography was very clear,” Barnes says. “Simon was always very understanding and respectful of what the V&A had already collected and didn’t want to duplicate the collection, what we already had here; and if there were photographers that we were both interested in, then we might collect complementary bodies of work, so that in the national interest there’s no sense of using public resources to duplicate caring for the same works.” Although it is an “unwritten policy”, Barnes says, “it was one that seemed to work very well”.

Has the Tate’s engagement with photography liberated the V&A’s collecting in this area? “Yes, in some ways,” Barnes says. “We didn’t feel the responsibility then to go out and collect highly expensive contemporary art photography that we didn’t already have in the collection because it was already in a national collection in the Tate, so it allowed us to focus on other things—perhaps, on the one hand, more historical material and, on the other, even more contemporary photography that the Tate wasn’t interested in acquiring.”

This is a curious detail: the V&A has long bought photographs directly from degree shows, and “supported photographers early on and shown them within the context of the history of photography in our galleries”, Barnes says.

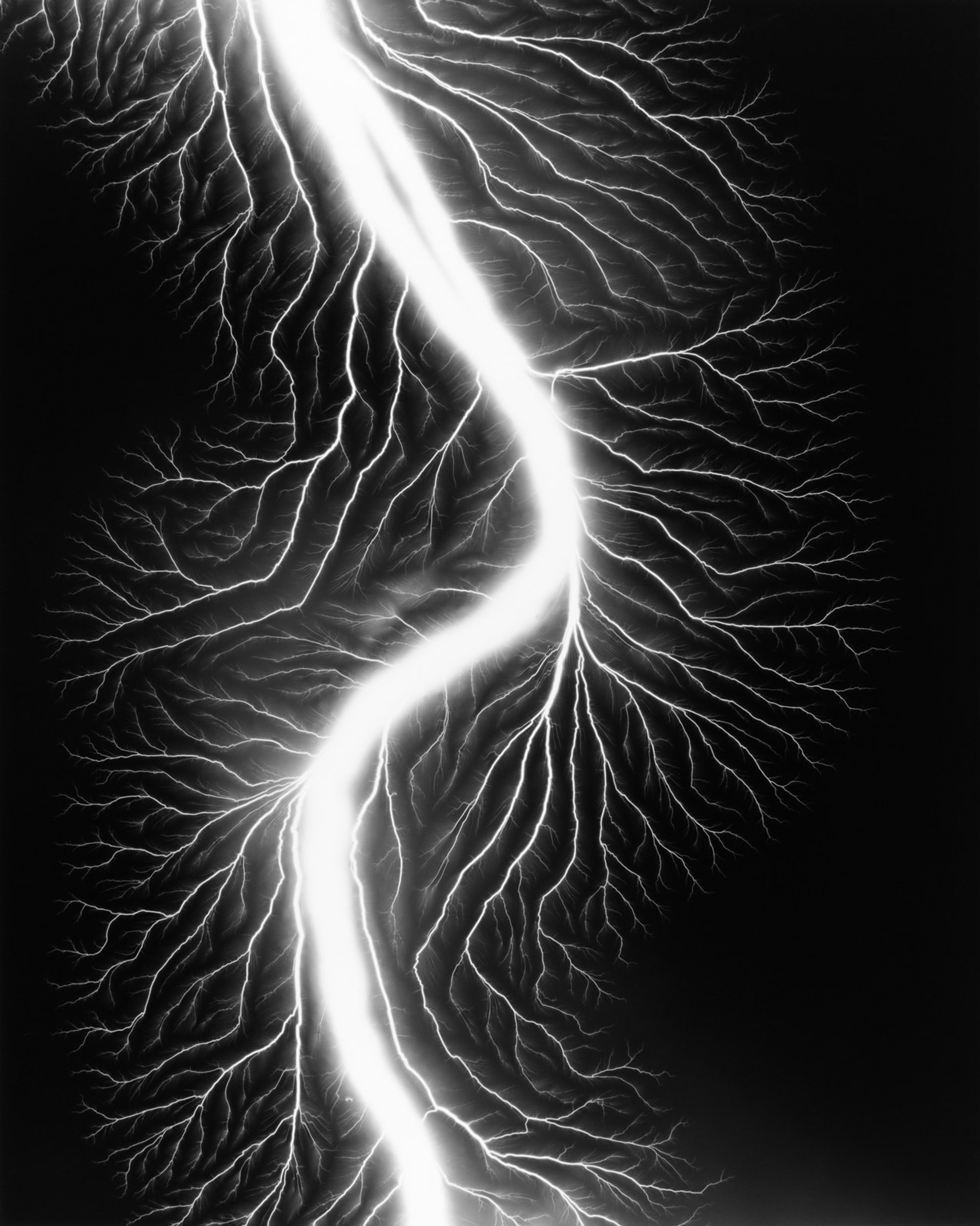

Hiroshi Sugimoto’s Lightning Fields 225 (2009) © The artist/V&A

But if McCullin’s show is a landmark event, it also shows just how far the Tate still has to go. That he is the first living British photographer to have a major career survey at the Tate is “really shocking”, Baker says. He argues that McCullin’s generation “has been very badly served by the overall ecosystem”. And while the Tate “bought a lot of work from Chris Killip and showed it at Tate Britain”, Baker says, it did not take his big touring career survey that was at the Folkswang Museum in Essen and travelled to the Museo Reina Sofía in Madrid—a selection of photographs was eventually shown at the Photographers’ Gallery when Killip was shortlisted for the Deutsche Börse prize.

“The situation for British photographers is extremely iniquitous,” Baker says, “and I can say that now I don’t work for Tate.” There has not been equivalent attention paid to photographers as to other artists, he says. “You’d have shows for mid-career painters and sculptors and all kinds of artists, regularly, but for some reason photography has never quite fitted into the vision of the directors of Tate Britain over many years. They have had group shows and they have acquired photographs, but they haven’t supported artists [until now] by giving them retrospectives and giving them their major show with a catalogue, the posters around town and all the things that come with it.”

The appointment in 2018 of Kate Bush, the former director of the Barbican Art Gallery, as the adjunct curator of photography at Tate Britain, is evidence that the gallery’s current director, Alex Farquharson, is placing greater priority on photography. Bush’s appointment bodes well, and her exhibition history is consistent with Baker’s work at the Tate. Speaking to The Art Newspaper in 2012 at the time of her Barbican exhibition Everything Was Moving, she argued for the artistic value of documentary photography. “Generally, documentary tends to be positioned in this place, which is about journalism and information,” she said, “and yet there are many great photographers whose remit is totally that of an artist—they are philosophical, they have a position in front of the world, they create fantastically beautiful compositions. But they also talk about the real—what is happening in the world.”

Martin Barnes at the V&A has a positive outlook on the future of photography in the big London museums. Their holdings are “part of a much wider collection of photographs that’s owned by the nation. It can’t possibly sit under one roof, and it benefits from its diversity in all of its locations and all of the different emphases that all those different institutions bring to it.”

• Don McCullin, Tate Britain, London, 5 February-6 May

• To read our interview with Don McCullin, see Don McCullin on why he is showing at Tate Britain even though he is ‘not an artist’

Photography in the London Collections

Victoria and Albert Museum

Number of photographs Recently doubled to 800,000 after the transfer of 400,000 images from the National Media Museum in Bradford. The V&A was the first museum to collect and show photographs.

Date range 1840s to the present.

Where to see them In the Photography Centre or in the prints and drawings room.

Staff Four curators, led by Martin Barnes, the senior curator for photographs.

Funding A photographs acquisition group, formed in 2013, aids with purchasing photographs for the collection.

Tate

Number of photographs Around 6,400. The Tate said last year that the number had “increased five-fold over the past decade”.

Date range 1860s to the present.

Where to see them In collection displays at the four Tate sites; at touring venues as part of the Artist Rooms initiative; and in the prints and drawings room at Tate Britain.

Staff Yasufumi Nakamori was appointed as curator of international art (photography) in 2018, taking over from Simon Baker. Emma Lewis is an assistant curator working on photography displays and exhibitions at Tate Modern. Tate Britain recently appointed Kate Bush as its adjunct curator of photography.

Funding A photography acquisitions committee, formed in 2010, has helped fund hundreds of purchases, though works can be acquired through other committees such as the Tate Americas Foundation.

Imperial War Museum

Number of photographs 11 million.

Date range 1850s to the present.

Where to see them In the collection displays and shows in London and Manchester. There is also a photograph visitor room, in the All Saints annexe, close to the London museum.

Staff Helen Mavin is the head of photographs. There are six members of staff developing the photograph archive and two more working on a digital project.

Funding From the IWM’s cross-media acquisition budget.

National Portrait Gallery

Number of photographs 250,000 original photographic images, at least half of which are original negatives.

Date range 1840s to the present.

Where to see them In the NPG’s collection displays or in the Heinz Archive and Library.

Staff A team of five curators, led by Magda Keaney, senior curator of photographs.

Funding No photography committee; acquisitions funded through a range of sources.