A lawsuit to stop the planned sale of three of the most notable works of art from Valparaiso University’s Brauer Museum of Art permanent collection was filed on 24 April at the Porter County Superior Court in Indiana. The paintings—Georgia O’Keeffe’s Rust Red Hills (1930), Frederic E. Church’s Mountain Landscape (1865) and Childe Hassam’s The Silver Veil and the Golden Gate (1914)—have been estimated to be worth a combined $20m, and Jose D. Padilla, the university’s president, announced publicly in February that the money generated from their sale would be used to improve freshmen dormitories with “amenities and features that prospective students value and expect”.

The lawsuit—which names Padilla, Valparaiso University and Todd Rokita, Indiana’s attorney general, as defendants—claims that the proposed “sale contravenes the donor’s intent”, which was “to serve and promote the cause of art education in both a practical and cultural way” by establishing galleries at the university to display the donated art. “Plaintiffs, and the public at large, will suffer irreparable injury if Valparaiso University violates the donor’s intent and liquidates assets of the trust for purposes not contemplated by” the donor. (The attorney general was named not because of any claimed malfeasance on his part, but to prod Rokita to stop the sale, since attorneys general are responsible for ensuring that charitable corporations comply with legal requirements, their assets are properly managed and spent and directors and officers fulfill their fiduciary obligations.)

Valparaiso University joins other educational institutions, such as Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee, Rockford College in Rockford, Illinois, Randolph College in Lynchburg, Virginia and Brandeis University in Waltham, Massachusetts, that in the past two decades have looked to prune their art collections in order to raise money for other campus needs.

The story of the origins of Valparaiso University’s art collection, which dates back to 1953, is somewhat more anomalous than those at the other colleges and universities. In 1953, a trust containing 400 artworks and approximately $188,000, set up in 1945 by Percy H. Sloan (1870-1950), a Chicago public school teacher, was donated to the university by Louis P. Miller, the trust’s executor. According to Richard Brauer, the founding director of the Valparaiso University Art Museum, later renamed the Brauer Museum of Art in his honour—who never met Percy Sloan but learned about him when he was hired by Valparaiso University to be its museum director in 1961—Sloan had spent almost 20 years looking for a museum that would accept his collection that mostly included landscape paintings by his father, Junius R. Sloan (1827-1900).

Percy Sloan was unable to find museums that would take just his father’s work, but he decided to purchase other landscape artists’ work, some of it by well-regarded 19th-century American painters. “He created a respectable ensemble of 19th-century American art in order to give context to the work of Junius,” Brauer said. Of the 400 artworks in the trust, 140 of them were by artists other than his father. Those non-Junius paintings “reveal the culture that inspired Junius and give Junius a reason for being”.

Three years after Percy Sloan’s death, Miller was able to strike a deal with Valparaiso University to accept all 400 paintings, and the agreement stipulated that the museum would “display a representative selection of the works of said Junius R. Sloan in a suitable place not less frequently than once in each year”.

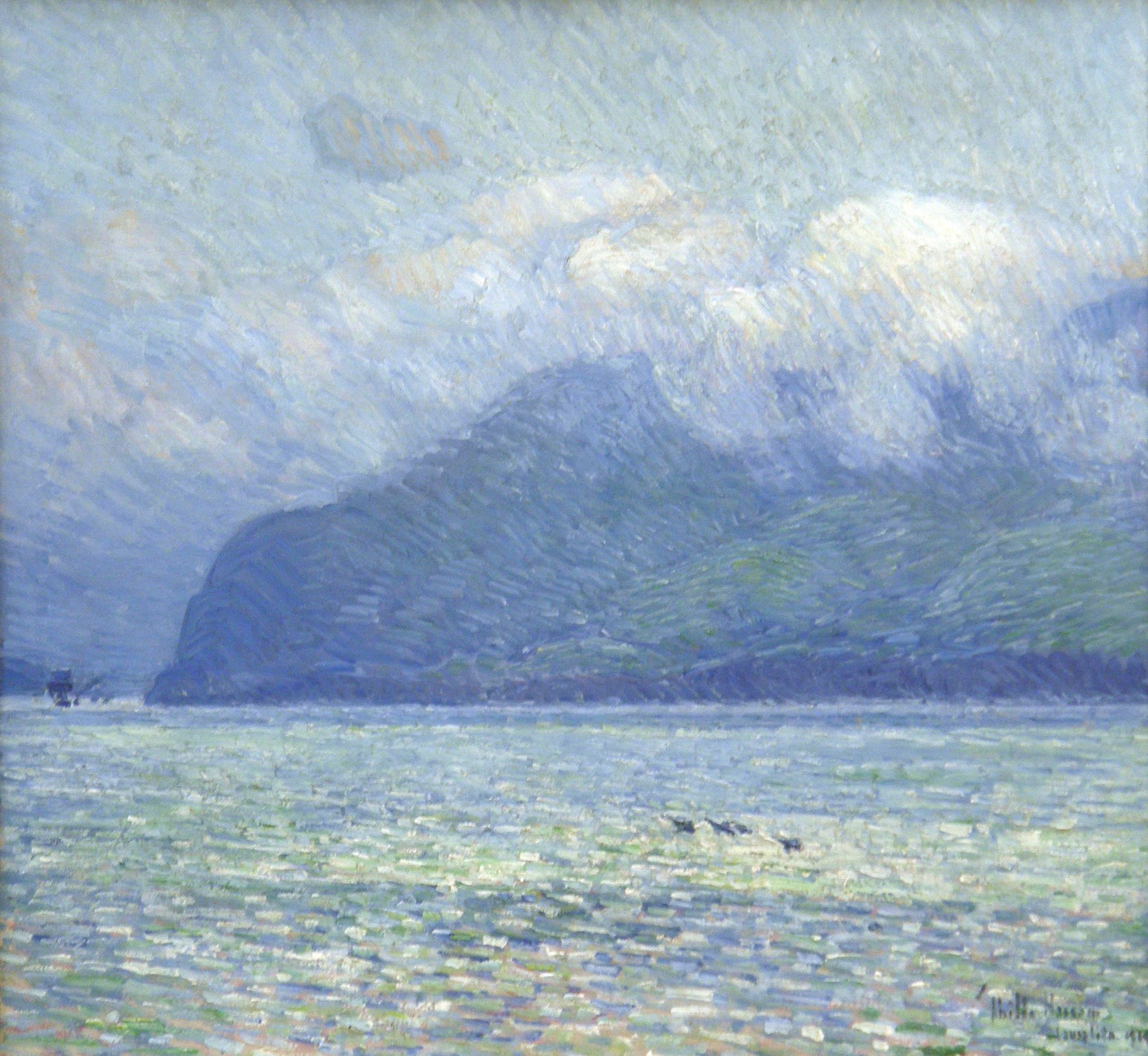

Childe Hassam, The Silver Veil and the Golden Gate, 1914, Brauer Museum of Art at Valparaiso University Via Wikimedia Commons

The plaintiffs in the lawsuit, Brauer and Philipp Brockington, a retired professor emeritus of law at the university and a benefactor of a fund specifically set up to endow the Brauer Museum of Art, claim that nothing in either Percy Sloan’s last will and testament nor the trust agreement with Valparaiso University “includes what is commonly known as a ‘deaccessioning policy’ to permit Valparaiso University to sell off objects donated or acquired using the trust corpus of the Percy H. Sloan Trust”.

In decades past, it was not uncommon for donations of objects to museums to come with conditions, such as demands that pieces regularly should be on display, donated items must be exhibited together rather than cherry-picked or nothing could be sold, but nowadays museum directors may refuse gifts that come with certain strings attached. Museum directors and curators are aware that tastes and priorities change, and they are very reluctant to make commitments that tie the hands of their successors. Brauer acknowledges that the Sloan trust donation of 1953 would not be welcome in 2023. “We struggle with the problem of conditions attached to gifts all the time,” he says.

Still, Patrick B. McEuen, the lawyer representing Brauer and Brockington in this action, says “attitudes change over 70 years, but restrictions do not”.

Another anomalous element to this dispute is that neither Brauer, 95, nor Brockington, 83, are related to Percy Sloan, a lifelong bachelor with no progeny, nor had they ever met him. Brauer has what McEuen calls “‘common-law standing’, because he can and will demonstrate a personal stake in the outcome of the litigation, which is the reputation associated with the use of his name on a museum at a university”. Brauer adds that “if the university goes through with the sale of these paintings, I want my name off the museum”.

Brockington’s connection to the art museum is through his contributions to the Brockington Reeve Endowment Fund, which aims to “acquire, restore and preserve” works of art and artifacts for the Brauer Museum of Art. According to the complaint, the endowment stipulates that “if the University finds the original intent of the donor can no longer be met, the university may hold and administer the fund ‘for a purpose that most closely coincides with the donors’ primary original intent, which is to support art at the Brauer Museum of Art’”.

Brockington says the paintings that the university seeks to sell form “the heart of the art museum” and that selling them would put the Brauer “in disrepute with other museums” around the country. Unlike Brauer, Brockington is not waiting for the university to sell these artworks before taking action: “I’ve already changed my will to make the Porter County Museum”—a local history museum also located in Valparaiso, Indiana—“the beneficiary of my estate.”

Unlike some other university museums, the Brauer Museum of Art has a particularly strong relationship with Valparaiso professors, especially with regard to the first-year core program. Classes are regularly held in the museum, where artworks in the collection are highlighted as they pertain to course subject matter, and “professors from around the campus come in to discuss their own research and evaluate one or more works in the collection as a jumping off point for discussion”, says Jonathan Canning, the museum’s current director. Salena Anderson, an associate professor of English, says that she has “used the Brauer in my classes in order to integrate the appreciation of art and literature”, most recently for a discussion of Alison Bechdel’s graphic novel Fun Home (2006). Other faculty members noted a meteorologist holding a class at the Brauer to point out cloud types in certain landscape paintings and a botanist using artworks to identify plant species.

Tabitha Porter, a freshman creative writing major at Valparaiso, says she regularly visits the museum, claiming that “this semester, I’ve been to the Brauer about six times on my own, and probably around nine or ten for classes and assignments that have been held there”.

Frederic E. Church, Mountain Landscape, around 1849, Brauer Museum of Art at Valparaiso University Via Wikimedia Commons

Of the three artworks scheduled for sale, only one of them had been purchased by Percy Sloan himself—the work by Hudson River School painter Frederic Church—while the other two had been bought by Brauer with funds included in the trust. Brauer described Percy Sloan’s own taste in art as “conservative, a little bit formulaic. He resisted modernism.” Of the O’Keeffe painting that Brauer purchased for the museum’s collection, Sylvia Preston, Percy’s Sloan’s aunt’s daughter and his closest and last remaining relative, who died in 2011, told Brauer that “Percy would have come to like it”.

Padilla’s announcement was met with condemnation by several museum associations, including the Association of Art Museum Directors (AAMD), the American Alliance of Museums, the Association of Academic Museums and Galleries and the Association of Art Museum Curators, as well as by a resolution from the university’s faculty senate, claiming that the loss of these artworks from the museum would diminish the prestige of both the university and its museum and that accepted museum field policy requires all proceeds from the sale of objects from a permanent collection be used solely for further acquisitions and not for other uses.

“The situation at Valparaiso is no different from any other prior instance in which a museum or its parent institution decides to sell art in order to fund capital investments, service debt or cover other operational expenses,” Julia Marciari-Alexander, the president of AAMD and director of the Walters Art Museum, said in a statement. “As we have stated in the past, we believe AAMD's rules apply to any art museum, even those that are not members of the Association, because they are the best practice approach to stewarding museum collections for future generations.”

New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art, for instance, recently announced plans to sell seven paintings from its permanent collection, including works by Edward Hopper, John Marin and Maurice Prendergast, but the announcement specified that the proceeds of the sale of these artworks at Sotheby’s on 16 May would be used solely to “support future acquisitions”, which makes it by most measures an acceptable practice within the museum field.

John Ruff, a senior research professor in Valparaiso University’s English Department, claimed that “if the three works were sold, it would really damage the prestige of the museum, which would damage the prestige of the university”.