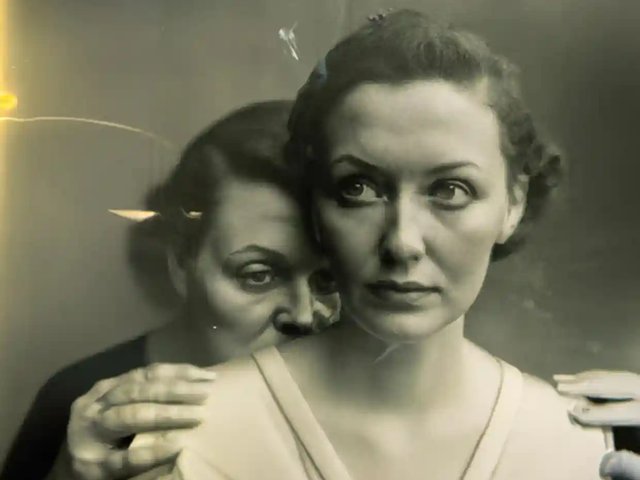

The photographer Boris Eldagsen recently caused surprise and a wave of discussion in the photography field when he won in a category of the Sony World Photography Awards with a synthetic image that he had produced using the AI or generative neural network DALL-E 2.

Eldagsen claims his intent was not to deceive, and he rejected the prize at the awards ceremony because he felt the organisers were not talking about the fact the image was synthetic. His aim, he says, was always to stir debate about the impact of these technologies on the way we think about photography. He also made his position clear, arguing that these synthetic images are not photographs and should not be accepted in competitions for photography. But is it so straightforward?

In a subsequent interview with the BBC, Eldagsen described these images as "promptography" not photography, making the distinction that a true photograph is made from light reacting with a sensitive surface, whereas these photographs are the result of prompts inputted into a neural network. However, this description masks the rather more complex and murky reality of how these neural networks can generate these images at all.

In order to generate such impressively life-like photographs, these neural networks are trained on huge datasets of millions of pre-existing photographs, which allow them to form the necessary "neural" connections to take a textual prompt and turn it into a photorealistic image. In a sense these systems don’t exactly produce anything new at all – they synthesise new images based on the data points of pre-existing photographs.

Through this they "learn" how light and lenses interact to create images in a conventional camera, but they don’t do this themselves, so in a way their outputs are almost closer to collage or 3D-modelling than to conventional photography. The problem here is that these systems struggle to generate images of things they haven’t been trained on, and so this will always be a major limitation to their creativity.

As Eldagsen said in an interview "photographic language has become a free floating entity separated from photography and has now a life of its own". At the same time, it is also worth noting that computational and generative photography is not exactly new, and we tolerate a wide range of post-processing effects being applied to photographs that bear no direct relationship to light, lenses and the other things we associate with traditional photography. Mobile phones increasingly employ neural networks to improve the images from their cameras, sometimes dramatically altering them in the process and producing an image that would not be possible through optics alone. So a middle ground between traditional photography and synthetic imagery also exists, one of "assisted" photographs that combine the best of both worlds.

Perhaps part of the problem with this debate, however, is that photography is used for a massive array of purposes, and to speak about all of them in the same breath is too ungainly to be useful. There are genres where we might agree that the undisclosed use of these images is problematic, like photojournalism, where the potential for them to be misused is enormous and could have genuinely dangerous consequences.

Synthetic imagery of news events is already circulating widely on social media (such as a recent image of presidents Putin and Xi), and in my own research I’ve found there is huge fear on newspaper desks about the dangers of news organisations using one of these images by mistake. It perhaps matters far less in the context of art, where these generative neural networks are a potentially powerful tool of expression, as Eldagsen himself argues.

PUTIN 🇷🇺- XI 🇨🇳 MEETING

— Jason Jay Smart (@officejjsmart) March 20, 2023

Putin attempting to persuade Xi. pic.twitter.com/yHbT9wOiXq

But a final question is whether the debate should focus less on whether these images count as photographs, and more about the moral right or wrong of how they work. There is growing evidence that the training data for many of these neural networks draws on copyrighted imagery by existing photographers, and there are a growing number of court cases brought against the companies behind the neural networks. Beyond the rights and wrongs of the images themselves, we should be asking if it is fair that photographers might find themselves losing out financially to systems that are only made possible in the first case because of their photographs.

• Lewis Bush is a London-based photographer. He is currently a PhD student at the London School of Economics in the department of Media and Communications and was formerly the course leader of the MA Photojournalism and Documentary Photography course at London College of Communication, University of the Arts London