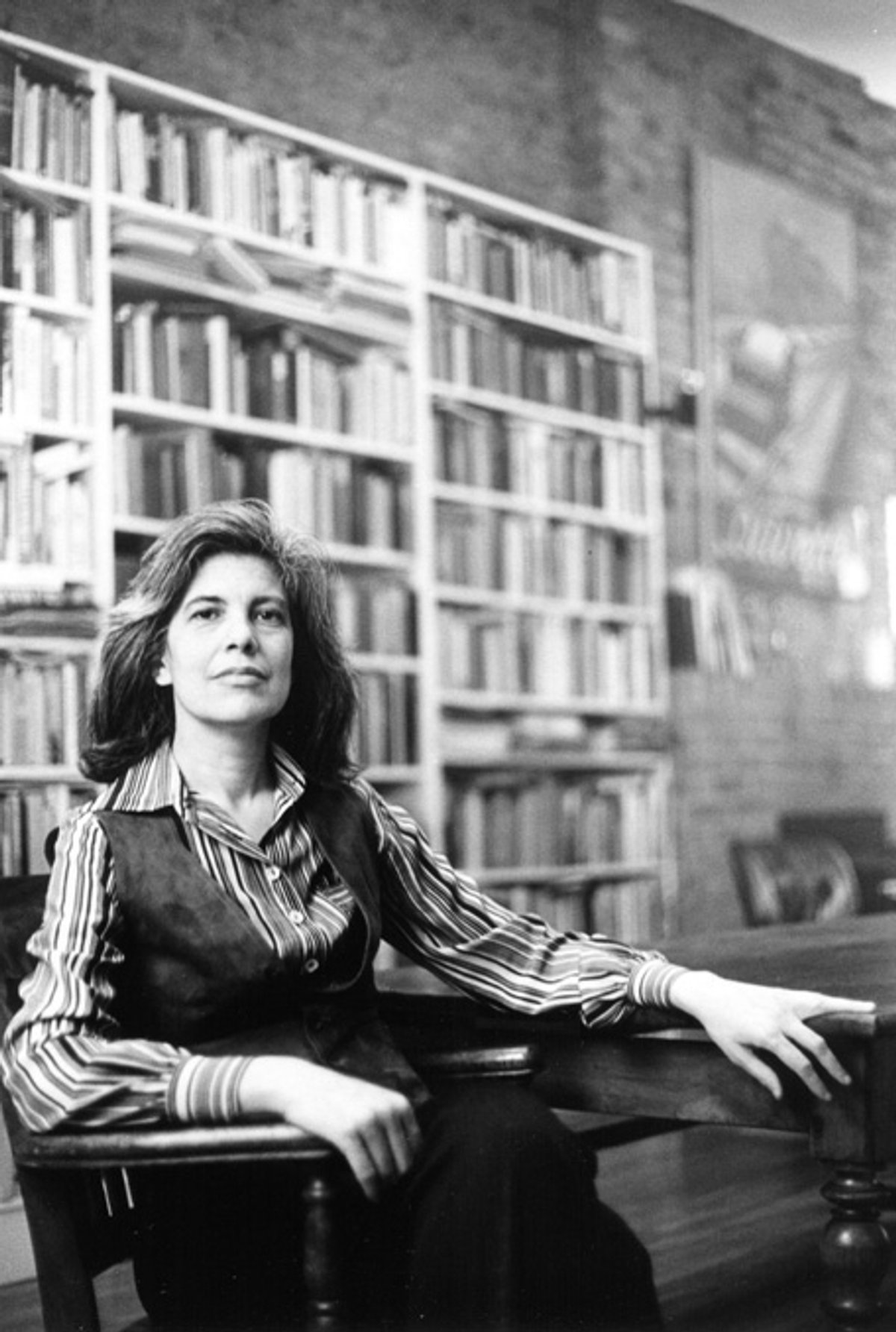

In the March 1978 issue of High Times magazine, Susan Sontag gave a rare interview about her new book, called On Photography. “It’s not about photography,” Sontag kept saying. Similarly, she insisted to The New York Times that she was not writing about photography, but about “the way we are now”. “The subject of photography is a form of access to contemporary ways of feeling and thinking,” she said.

Sontag struggled to be understood. Photography was considered an illegitimate art form by many of her art critic contemporaries. But Sontag understood how photography acted as an “exemplary activity” in society—one that uniquely explored “everything that is brilliant and ingenious and poetic and pleasureful”, she told High Times.

“Sontag was prescient in her understanding of photography’s role in contemporary life,” says Mia Fineman, a photography curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, who has contributed to the first ever illustrated edition of Sontag’s now seminal 1977 book, to be released on 13 September by the Folio Society. “While most critics were worrying about photography’s status as art, Sontag was thinking about photography in relation to consumer culture.”

On Photography comprises a collection of essays that Sontag originally published in the New York Review of Books between 1973 and 1977. Although she was a brilliant student—she studied variously at the University of California, Berkeley, the University of Chicago and Harvard—Sontag’s writings did not come from the closed loop of academia. She was writing for the people pounding the pavements of New York, sitting in bars or cafes or on the subway, looking for a quick intellectual buzz.

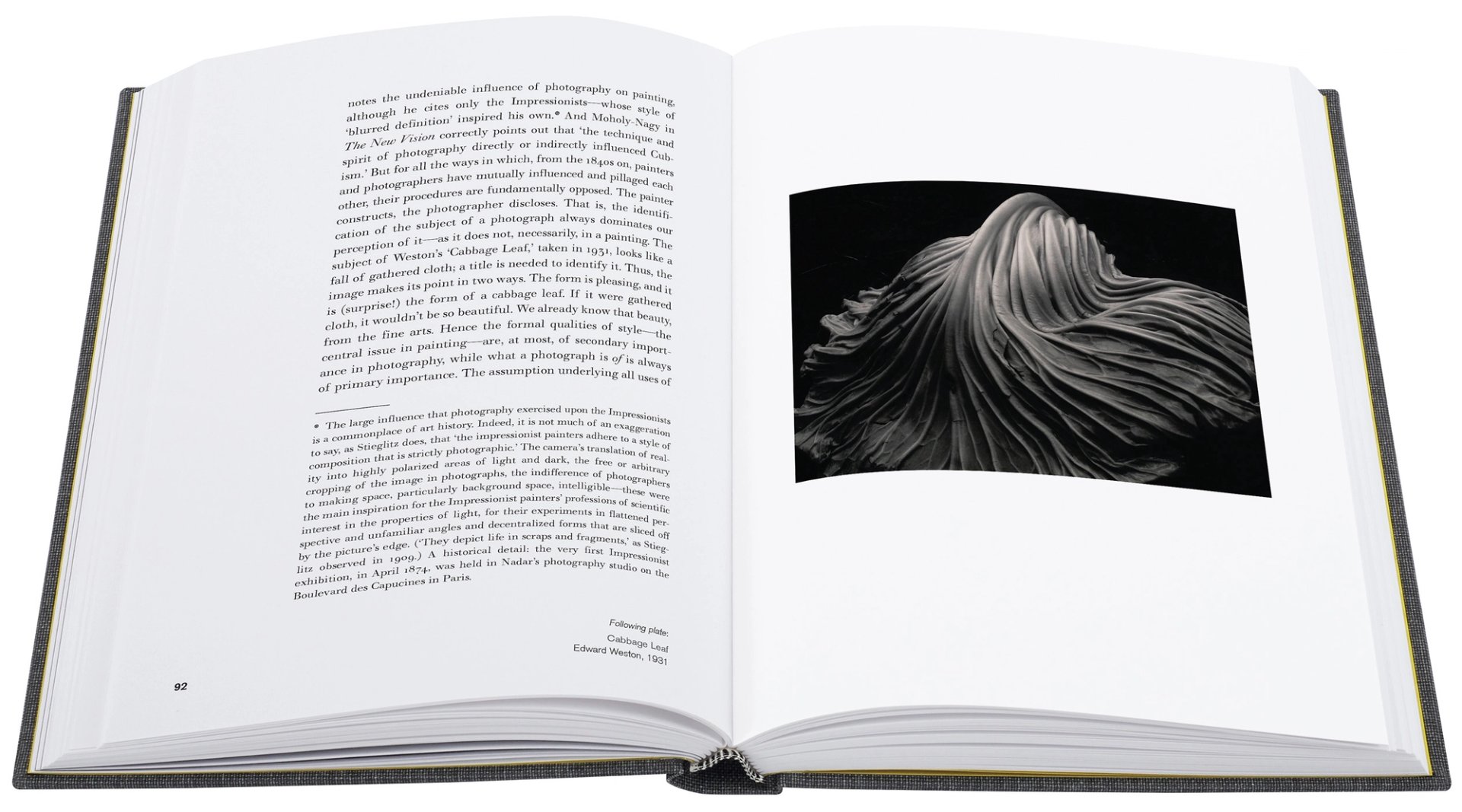

Each essay took her around six months to write; each word, then, was carefully considered, every sentence sweated over. But her lyrical discussion of abstract concepts like representation and reality remain a necessary lesson for any aspiring interpreter of art and life.

The essays are revealing of the author. Sontag was the daughter of Jewish New Yorkers of Polish and Lithuanian descent who had built a comfortable home in Long Island. Although she came from a well-off family, Sontag faced many early challenges. In an interview with the Guardian newspaper, she spoke of a father almost always away on business, and a cold, distant mother who “flinched if you touched her”. Her father died of tuberculosis when she was just five. Soon after leaving home, at the age of 17, Sontag agreed to marry one of her lecturers after a ten-day courtship. She soon became a mother, but the marriage only lasted nine years.

Throughout her youth, Sontag had to carve out a career of her own making, in an industry peopled and controlled by older men. Fineman admits that, reading the book today, one discerns “logical inconsistencies and self-contradictions”. They help us to understand the woman who wrote them.

Sontag’s words are now routinely quoted in any debate about the impact photography has had, and continues to have, on every facet of modern life. Early in the book, she calls photographic imagery “the most irresistible form of mental pollution”. She wrote: “Needing to have reality confirmed and experience enhanced by photographs is an aesthetic consumerism to which everyone is now addicted.”

Sontag died of leukaemia in New York in 2004, three years into the War on Terror and six years before the birth of Instagram. But already in the 1970s, Sontag understood that, with a camera in hand, “having an experience becomes identical with taking a photograph of it”.

The book was not entirely well received. To this day, photography theorists often assume Sontag was an opponent of the medium. “There was a widespread misunderstanding of her fundamental attitude toward the medium,” Fineman says. “Many critics believed that she was against photography, that she thought the medium was terribly dangerous or destructive. In fact, Sontag loved thinking about photographs.”

The first dedicated photography exhibition at a major UK cultural institution came as late as 2003, when Tate Modern staged Cruel and Tender: The Real in the Twentieth-Century Photograph. Sontag was writing almost three decades earlier, when many academics were still engaged in the limited debate of whether photography can “truthfully” reflect reality—whether an image can ever be “real”.

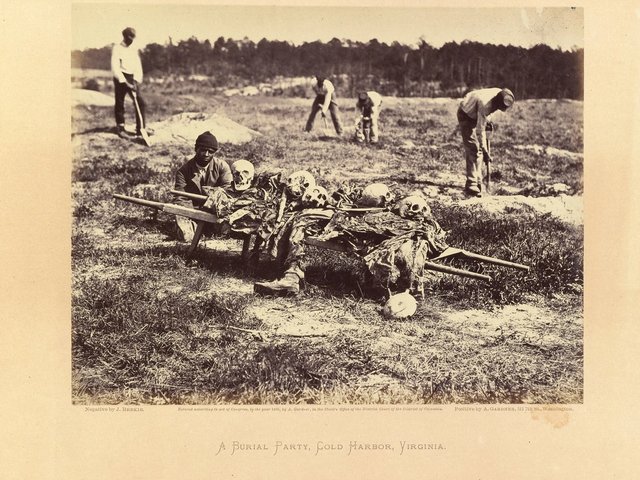

Sontag saw through it. She was one of the first theorists to write about photography’s ability to deceive and manipulate, its potency when deployed as propaganda, its capacity to exploit the truth. She called the camera “a predatory weapon”. She observed: “Photographs, which cannot themselves explain anything, are inexhaustible invitations to deduction, speculation, and fantasy.”

This, Fineman says, was Sontag at perhaps her most prophetic. “Her insights about images of atrocity and compassion fatigue remain painfully relevant today. She understood as well that photography reflects everything that is destructive and polluting and manipulative in our life.”

Writing in an introduction to the new edition, Fineman expands on this point. “On Photography explores the ethical implications of camera vision in the realm of reportage,” she writes. “The voyeurism and complicity involved in taking and looking at photographs of atrocity, and the dangers of compassion fatigue, of becoming desensitised to images of suffering.”

In New York and London, the established photography community—the gatekeepers of the industry—remain to this day fairly conservative in outlook, instinctively resistant to new ideas. It is worth remembering how the gatekeepers of Sontag’s day responded to On Photography.

In March 1978, the International Center of Photography in New York held a symposium to discuss the book. During the session, the Center’s director, Cornell Capa, said: “To date, photographers have either ignored the book, denied having read it, or are furious about personal implications that they resent.”

A month later, the critic Colin Westerbeck wrote in Artforum magazine: “Sontag is prejudiced. She doesn’t see photographs as individual works in the same way that a bigot doesn’t think of blacks or Italians or Jews as individual people.”

But Sontag’s ideas remain as resonant in 2022 as the day she wrote them. “The power and originality of Sontag’s book lie in her eagerness to engage with photography’s promiscuity,” Fineman writes. “Its voraciousness, and the profound role the medium has played in shaping the contours of modern consciousness, for better or worse.”

The Folio Society edition of On Photography by Susan Sontag, published 13 September, 224pp, £90.00, hb

A selection of pages from On Photography by Susan Sontag.

courtesy The Folio Society