Arguments over whether the Vermont Law School will be allowed to cover up an artist’s mural that African American students there find objectionable, or if the artist’s rights as defined by federal statute will compel the school to keep it on view, were presented last week in an appellate court in Vermont.

The ruling likely will be closely watched by other institutions and municipalities around the country where other murals—and questions about what to do with them—have become the focal points of sometimes-bitter debates.

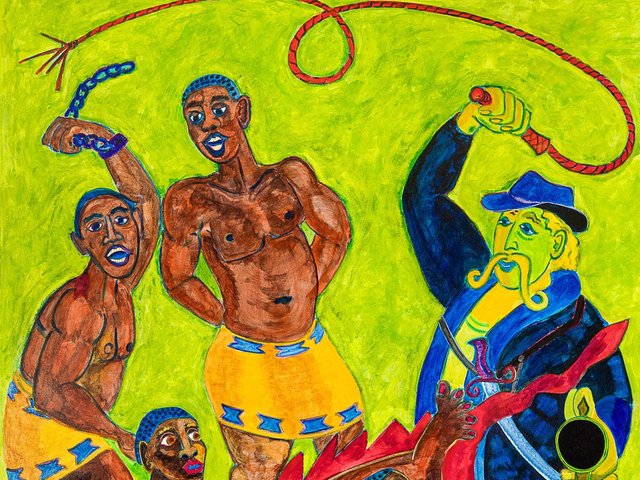

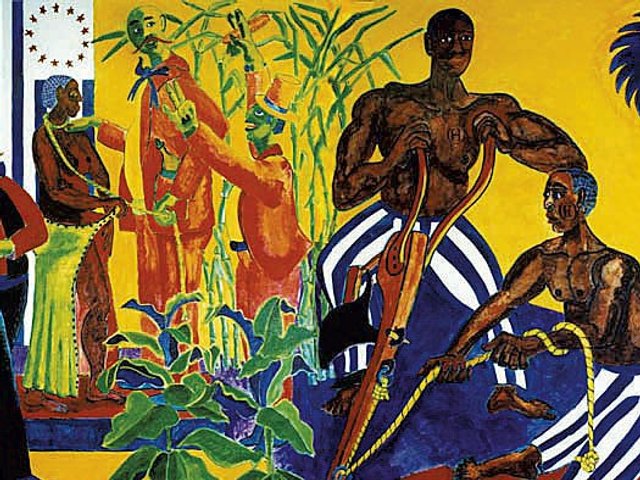

The murals in question were commissioned in 1993 by the Vermont Law School (now the Vermont Law and Graduate School, or VLGS), and the artist Sam Kerson, 76, who currently lives in Trois-Rivières, Québec in Canada, was selected to create painted images celebrating Vermont’s role in the underground railroad, which enabled enslaved people in the US South to escape bondage and flee to safety in the northeast and Canada. In 1994, the murals were painted directly onto the sheet rock walls in Chase Hall at VLGS in South Royalton, Vermont. Each mural is eight feet by 24 feet in size, the first entitled Slavery and containing four scenes: the capture of people in Africa, selling humans in the US, slave labour and insurrection. The second mural is entitled Liberation and also contains four scenes: images of Harriet Beecher Stowe, John Brown and Frederick Douglas Harriet Tubman arriving in Vermont, South Royalton Vermont residents sheltering the formerly enslaved and Vermonters providing travel aide to the formerly enslaved with the state capital in the background.

The initial reception of the murals was positive, but by 2020 some students voiced objections to the images, calling them “Sambo-like” and racist, based on the way in which Kerson depicted the enslaved figures. “The law school acknowledged that Kerson’s intentions in creating these murals were good,” says Justin Barnard, the lawyer representing the school in this action. “However, over the decades, and especially after the death of George Floyd in 2020, the school administrators decided that they could not avoid the voices of students who were critical of the murals.”

He added that “the meaning of art changes over time, and it raises interesting moral and philosophical questions over what to do with controversial depictions of people, especially when the artist is not a member of the group being depicted”.

VLGS’s initial response to the protests by African American students was to announce plans to paint over the murals or to glue acoustic tiles to the wall, which the artist informed the institution would violate his rights under the Visual Artists Rights Act (VARA), a 1990 amendment to the US Copyright Law that protects the reputations of living artists and prevents the owners of artworks of “recognised stature” from destroying them. It also forbids owners of these pieces from altering them in some way without the artist’s approval.

Kerson hired some carpenters who attempted to remove the murals—a provision of VARA empowers artists to take back artworks that owners otherwise would damage or destroy—but found that doing so was not feasible. Eventually, VLGS decided to put a series of white panels directly in front of, but not touching, the murals, which would keep them from being viewed without actively damaging them. This led Kerson to file the initial lawsuit.

In October 2021, a district court sided with the law school, finding that “the intentional and permanent walling-off and blocking from view of an artistic work of recognised stature, incorporated into a building, does not rise to a cognisable claim under VARA”. Kerson hopes that the US Court of Appeals will reverse that decision.

Kerson’s lawyer, Steven Hyman, claimed that the district court was “wrong on the law” and that VLGS’s actions are preventing “the artist from having his artwork seen. VARA requires art to be seen. When you block people from seeing it, you are prejudicing the artist’s reputation.” He added that if the district court’s ruling is upheld, “you are undoing VARA at its very core”.

Debates over murals have caused controversy across the country in recent years. In Georgetown, Texas last year, a mural entitled Be Your Own Person, painted by high school students on the side of a building in the town square, was attacked by local residents for promoting an LGBTQ ideology based on its inclusion of the rainbow flag. Similar criticism arose last fall in Grant, Michigan over a high school student’s mural on the wall of a middle school health centre. A mural on the back side of a tattoo parlour in Midvale, Utah aroused indignation for its depiction of a naked man and woman “experiencing ecstasy”.

Perhaps most contentiously—and most similar to the Vermont case—a mural painted in 1936 on the wall of a high school in San Francisco that shows George Washington next to a dead Native American and enslaved Black people he owned, as well as a Depression-era mural on the wall of a Chicago Public Schools administration building that features Native Americans serving a white man, have sparked intense debate and criticism.

In 1979, a 1930s-era mural by Walter Beach Humphrey that showed drunken Native Americans being swindled out of the land they had owned that eventually became the grounds of Dartmouth College, was covered after students at the college protested the imagery. In 2018, that mural was removed by the college and put in permanent storage.

Artworks created in the years before the enactment of the Visual Artists Rights Act would not be protected by the statute.