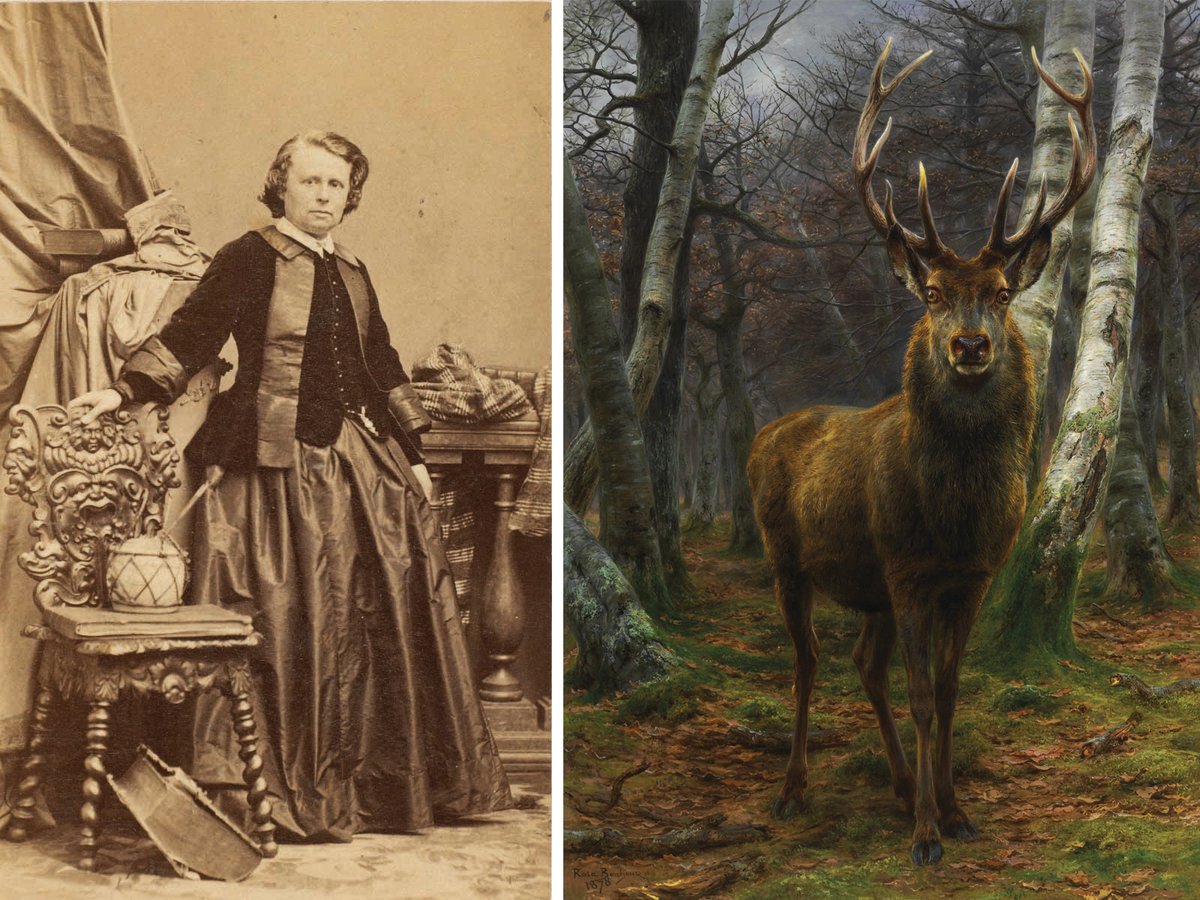

Two rabbits nervously nibble at carrots, ears twitching. A wounded eagle strains in mid-air. A stag pauses in a forest, honeyed eyes fleetingly fixed on ours. The animals in Rosa Bonheur’s works brim with emotion. “Her realism is her way of respecting them,” says Leïla Jarbouai, the curator of an exhibition dedicated to the 19th-century French artist at the Musée d’Orsay. “She conveys the expression of their souls through their eyes and their attitudes, by painting them carefully and faithfully. They are subjects in themselves.”

Coinciding with the bicentenary of Bonheur’s birth, this career-spanning survey will bring together around 200 works, from paintings and drawings to sculptures and photographs. “In France she’s associated with cattle paintings,” Jarbouai says, above all Ploughing in the Nivernais (1849), which won her a medal at the Salon with its meticulous attention to the gleaming oxen and freshly turned soil. “The exhibition will reveal to visitors her paintings of wild beasts, horses, and other wildlife. It will show that she can’t be reduced to a painter of country life and livestock.”

Dedication to naturalism

Bonheur was trained by her painter father, and first exhibited at the Salon aged 19. Her dedication to naturalism and capturing the individuality of animals won her admirers. In the early 1850s she attended horse markets in Paris, wearing men’s clothes (with permission from the police) to avoid attracting unwanted attention while sketching.

“Her realism is a way of respecting them”: Rosa Bonheur’s painting of a wounded eagle, L’aigle Blessé (around 1870) Photo: © Museum Associates LACMA; RMN Grand Palais

On display will be little-known sketches by Bonheur, among them a charcoal drawing on linen for her best-known painting, The Horse Fair (1852-55), a monumental scene of clattering hooves, snorting muzzles and loose manes. Recently discovered by the team at Château de By, the museum dedicated to the artist on the fringes of Fontainebleau Forest, the work has been restored for its first public outing. Jarbouai is also keen to draw attention to the unexplored romantic side of Bonheur’s work, visible in an inky-blue lithograph of wolves and a lonely rider in Scotland.

Selling her art directly to collectors, Bonheur found fame at home and abroad. The Belgian dealer Ernest Gambart, who produced prints of her paintings and organised publicity tours, played a part in her international success. After 1853, though, she rarely participated in the Salon. “French visitors didn’t know her work anymore,” Jarbouai says. “They knew the woman, the legend, better than her art.” According to the curator, the sale of thousands of studies from her studio in 1900 contributed to “the collapse of the paintings’ rating”. In other words, her reputation dipped. “Art history and the notion of avant-garde didn’t leave room for Bonheur’s animal art,” Jarbouai adds. With this exhibition, the Musée d’Orsay hopes to reclaim space for both the artist and her creations.

• Rosa Bonheur (1822-1899), Musée D’Orsay, Paris, 18 October-15 January 2023