Van Gogh in America, at the Detroit Institute of Arts (2 October-22 January 2023), is the first show to tell the story of how US art lovers discovered Vincent’s work in the early 20th century. After a slow start, American collectors eventually flocked to buy his paintings, with many of their acquisitions ending up in museums. The exhibition is backed up by meticulous research, in a detailed catalogue.

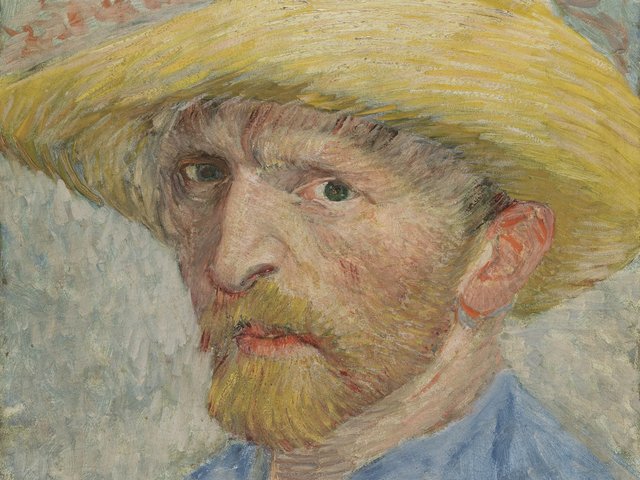

Van Gogh’s Self-portrait (August-September 1887), when it came to Detroit in 1922 it was the first work by the artist to be acquired by a US museum Credit: Detroit Institute of Arts (City of Detroit Purchase, 22.12)

With 59 Van Gogh paintings and 15 drawings, Van Gogh in America is curated by Detroit’s Jill Shaw. Visitors will not only have the chance to see how Van Gogh conquered the US, but also get to enjoy a fully representative sample of his work.

The Detroit exhibition includes some of the artist’s finest paintings: Starry Night over the Rhône (September 1888, Musée d’Orsay, Paris); Van Gogh’s Chair (December 1888-January 1889, National Gallery, London); and a version of The Bedroom (September 1889, Art Institute of Chicago).

Van Gogh’s The Bedroom (September 1889), donated to the Art Institute of Chicago in 1926 Credit: Art Institute of Chicago (Helen Birch Bartlett Memorial Collection, 1926.417)

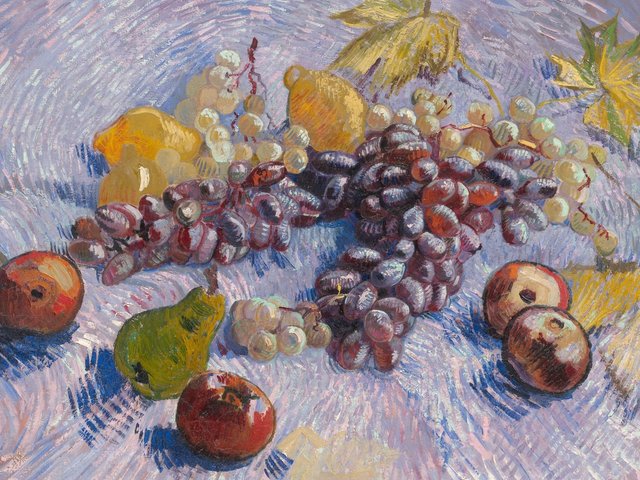

Visitors will also have the opportunity to see privately owned works which are only lent occasionally: Orphan Man (1882-83, from Nancy and Sean Cotton); Head of a Peasant Woman (1884-85, from the Abelló collection, Spain); Head of Gordina de Groot (May 1885); Basket with Oranges (March 1888); The Plain of Le Crau (May 1888, from Texas); Harvest in Provence (June 1888); and The Novel Reader (November 1888, from Brazil).

The story of how the US discovered Van Gogh begins in 1912, when the Pennsylvania pharmaceutical chemist Albert Barnes became the first American to buy a painting: a portrait of The Postman (Joseph-Etienne Roulin) (spring 1889). He later acquired six more works, which are all now displayed at the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia (Barnes required that they should not be lent, so they will be missing in Detroit).

Later in 1912, two other paintings came to the US: Katherine Dreier purchased Adeline Ravoux (June 1890, now at Cleveland Museum of Art) and John Quinn bought a self-portrait (summer 1887, Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, Connecticut). Both pictures are in the Detroit show. Dreier, herself an artist (and suffragette), described her discovery of Van Gogh as “stepping out of a stuffy room into glorious, bracing air”.

The American public first saw Van Gogh’s work in 1913, at the International Exhibition of Modern Art, known as the Armory Show. Starting in New York, it moved on to Chicago and Boston. This huge exhibition, with over 1,300 works, included 21 Van Goghs. None of the Van Goghs sold.

By the eve of the First World War there were only five Van Gogh works in US collections. This compared with 156 in Germany, where collecting of Van Goghs had really taken off in the early 1900s.

Van Gogh’s first modest one-man show in America was opened in 1915 by a New York dealer, Marius de Zayas, who ran the Modern Gallery. Although 17 works were shown, once again none sold.

In 1920, New York’s commercial Montross Gallery presented a larger show, with 32 paintings and 35 drawings from the Van Gogh family collection, which was managed by Vincent’s sister-in-law Jo Bonger. This time three works, including The Sower (autumn 1888), were sold—all going to the Pennsylvania clergyman Theodore Pitcairn.

Van Gogh’s The Sower (autumn 1888), sold at the 1920 Montross exhibition to clergyman Theodore Pitcairn Credit: Hammer Museum, Los Angeles (gift of Dr Armand Hammer, AH 91.42)

Two years later the Detroit Institute of Arts became the first US museum to buy a Van Gogh: a self-portrait of the artist wearing a straw hat. This makes the city a most appropriate venue for the current exhibition. The price of the self-portrait was $4,200. In 2013 the painting was valued at $80m-$150m, although it is now worth considerably more.

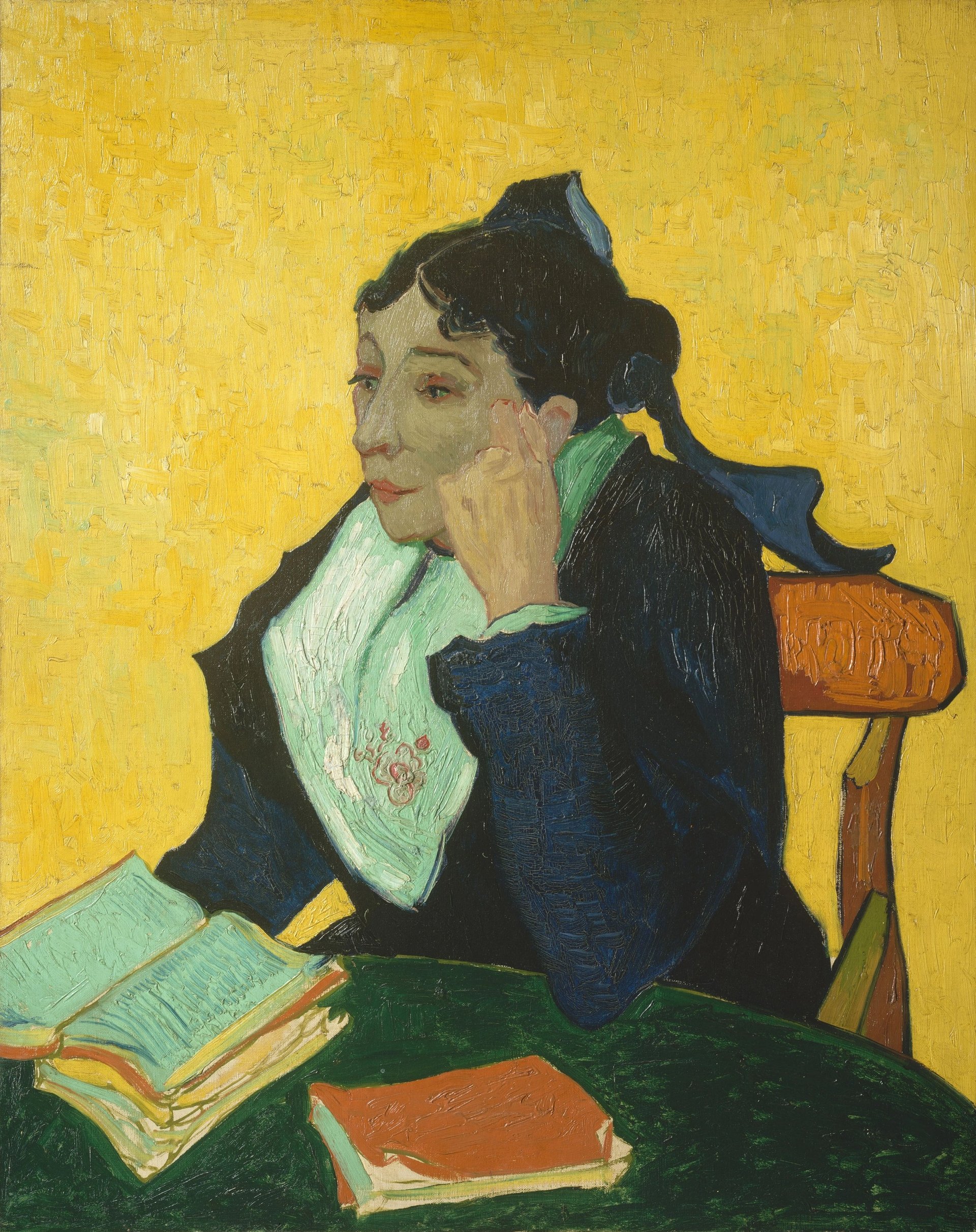

Van Gogh’s L'Arlésienne: Madame Joseph-Michel Ginoux (November 1888), exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art, New York in 1929 Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (bequest of Sam A. Lewisohn, 1951)

When New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) opened in 1929 it held a spectacular loan exhibition, which included 26 Van Gogh works. By this time there were a number of distinguished American Van Gogh collectors who lent paintings. These included L'Arlésienne: Madame Joseph-Michel Ginoux (November 1888), which had been bought in 1926 by the New York entrepreneur Adolph Lewisohn. This portrait was later bequeathed to New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The next museum acquisitions were all by institutions in the Midwest. In 1926, the Art Institute of Chicago received a magnificent gift from Frederic Clay Bartlett, which included three Van Goghs: Lullaby: Madame Roulin rocking a Cradle (La Berceuse) (January 1889), Terrace and Observation Deck at the Moulin de Blute-Fin, Montmartre (early 1887) and The Bedroom, plus another work which a few years later was deemed a fake: Still Life: Melon, Fish, Jar.

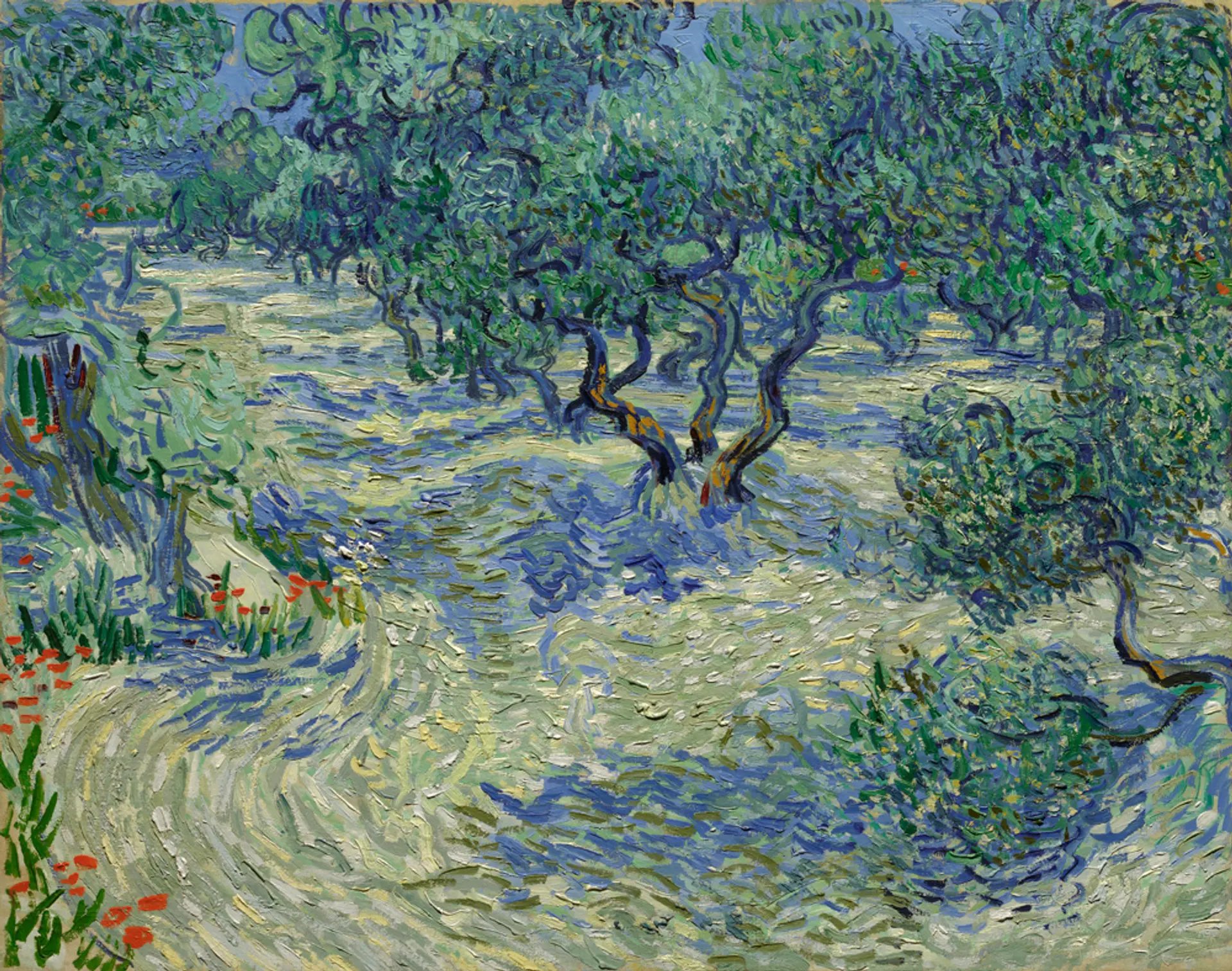

Van Gogh’s Olive Trees (June 1889), acquired in 1932 by what is now the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City Credit: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri

In 1932, Olive Trees became the second Van Gogh to be bought by a US museum, when it was acquired by what later became the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City.

Two years later the Saint Louis Art Museum purchased Stairway at Auvers (June-July 1890). The Toledo Museum of Art bought Houses at Auvers and Wheatfields with Reaper (both June 1890) in 1935.

Van Gogh’s Stairway at Auvers (June 1890), acquired in 1935 by what is now the Saint Louis Art Museum Credit: Saint Louis Art Museum (purchase 1.35)

But although these early museum acquisitions were important, in popular imagination Van Gogh’s rise to fame came with the publication in 1934 of Irving Stone’s fictionalised biography Lust for Life (which became even more influential after the 1956 film). Even today, many of the myths surrounding the artist can be traced back to this novel.

Van Gogh’s first one-man museum exhibition came a year after the Lust for Life book, when MoMA showed 127 works. The show went on to travel to nine further North American venues and altogether it was seen by nearly a million visitors. It was not until 1941 that a New York institution bought a Van Gogh, when MoMA acquired Starry Night (June 1889).

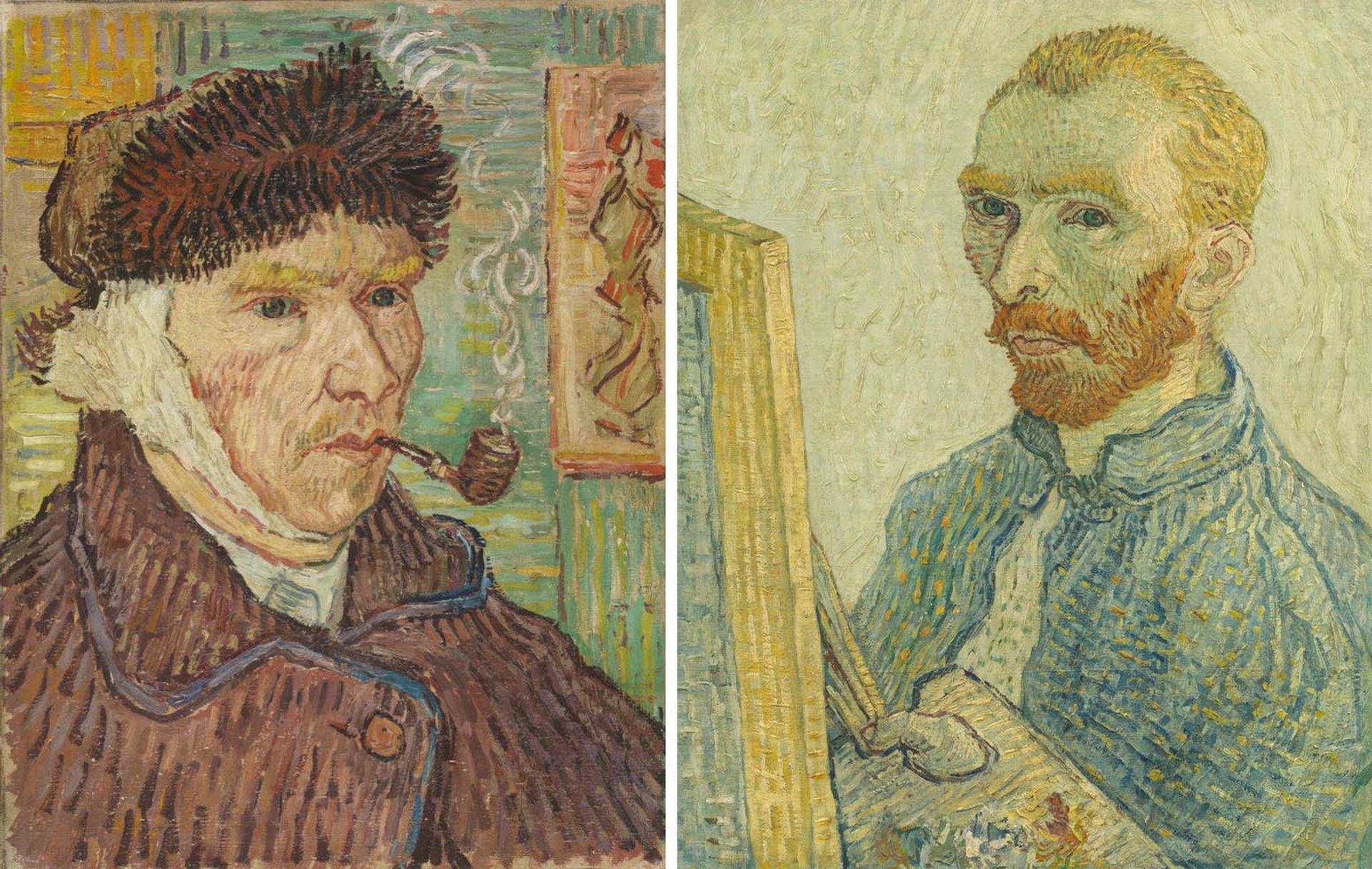

Portraits of Van Gogh by anonymous artists, at the Fogg Museum and the National Gallery of Art Credits: Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Cambridge, Massachusetts (bequest of Annie Swan Coburn, 1934.35) and National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

What may come as a surprise is quite how many forgeries and fakes ended up in US museums, when they were assumed to be authentic. These include two self-portraits. One of the artist with his pipe was bought by the Chicago collector Annie Coburn in the late 1920s and bequeathed in 1934 to the Fogg Museum in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The other, described by the New York Times when it was bought in 1928 as “the best thing [Van Gogh] ever did”, was acquired that year by the New York banker Chester Dale and bequeathed to National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, in 1963.

In addition to the two self-portraits and the Bartlett still-life in Chicago, other forgeries and fakes accessioned by American museums include: Still life with Vase of Flowers (Philadelphia Museum of Art); Landscape (National Gallery of Art); and a drawing of a harvest scene (Art Institute of Chicago). It goes without saying that none of these fakes are being shown in the Detroit exhibition.

The Van Gogh in America blockbuster will celebrate the centenary of the first acquisition of one of the artist’s works by a US museum, the Detroit self-portrait. Its catalogue reveals the painstaking research behind the project, including an important essay by Susan Stein, a curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Borrowing Van Goghs is now a real challenge, but with 59 paintings, the Detroit exhibition will have the largest number of works in an American show for more than 20 years.