Kirk Douglas, who portrayed Vincent van Gogh in Lust for Life, died last week, aged 103. The 1956 film, based on Irving Stone’s 1934 novel, helped turn both the artist and the actor into global stars. Directed by Vincente Minnelli, the film has had a key role in shaping the public’s perception of Van Gogh today, 64 years later.

Douglas once said of acting in Lust for Life that “the painful experience was probing into the soul of a tormented artist”. The actor’s success was due to totally immersing himself in the part. His wife Anne once said that he would return home after filming still reflecting Van Gogh’s character. They even gave their son Peter, who was born during the production, the middle name Vincent.

To add to the authenticity, much of the film was shot on location in the places where Van Gogh had lived and worked, leading up to his suicide in Auvers-sur-Oise. As Douglas recalled in his 1988 autobiography The Ragman’s Son: “It was horrible to be standing in the field where he painted his last painting—the crows in the wheatfield—leaning on the same tree with a gun in my hand.”

Vincent van Gogh’s Wheatfield with Crows (1890) Courtesy of Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

To prepare for his role, Douglas practiced painting swooping birds, to portray the moment when the artist was finishing Wheatfield with Crows (1890). In the film, Douglas completes the picture by almost stabbing the canvas with the marks of black crows. He then abandons his painting and leans against a tree, writing a final note and quickly pulling a gun from his pocket. We now know that Wheatfield with Crows was not his final painting, it was done some days before the shooting. But partly thanks to Lust for Life it still remains the picture which is closely associated with the artist’s suicide.

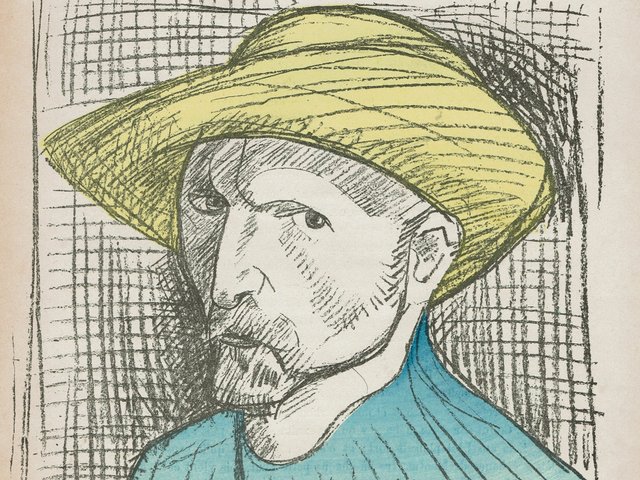

Vincent van Gogh’s Self-portrait (1887) Courtesy of Detroit Institute of Arts

Douglas even managed to take on the physical appearance of the artist, or at least the Van Gogh we know from his self-portraits (there are no surviving photographs of the artist after the age of 20). The actor studied the self-portraits carefully, modelling himself particularly on the one with the straw hat, now at the Detroit Institute of Arts. This painting will form the centrepiece for Detroit’s coming exhibition Van Gogh in America (21 June-27 September).

Where Lust for Life added to the mythology was Douglas’s presentation of Van Gogh as a highly strung tormented artist, impulsive and filled with pent-up emotions. As the definitive 2009 edition of Van Gogh’s letters emphasises, the artist was a much more thoughtful soul, with an absolute determination to pursue his goals.

The Lust for Life film has proved to be an inspiration for later artists. Marc Chagall was so touched by it that he approached Douglas, asking whether he would be willing to play him in a filmed version of his autobiography, Ma Vie. Douglas acquired four of Chagall’s pictures, but later said that “I never wanted to portray another painter”.

The earliest film ever made about Van Gogh had been the French director Alain Resnais’s black and white documentary Van Gogh in 1948. Lust for Life was the first dramatised production—and in colour. From the 1970s there has been a continuous stream of films on the artist, including the recent animated version Loving Vincent.

Willem Dafoe as Vincent van Gogh in Julian Schnabel’s film At Eternity’s Gate Courtesy of the artist and the 75th Venice International Film Festival

The latest is Julian Schnabel’s At Eternity’s Gate (2018). At the time of its launch, Schnabel commented: “I loved Lust for Life when I was a child, but it’s got every cliché. It’s kind of the opposite of the film we made.” Although At Eternity’s Gate avoids many of Lust for Life’s embellishments, Schnabel has introduced new myths—most notably accepting a fake sketchbook of Arles drawings and presenting the artist’s death as murder, not suicide.

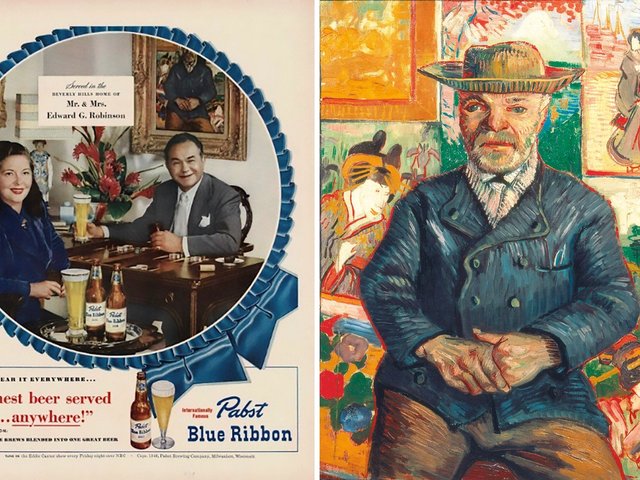

• Although Douglas never bought a work by Van Gogh, quite a number of US film actors and directors became collectors: Edward Robinson owned Portrait of Père Tanguy (1887); Harold Hecht owned a drawing of View from Montmajour (1888); Buddy De Silva owned drawings of Joseph Roulin (1888) and The Langlois Bridge (1888); Josef von Sternberg owned the drawing Corner of a Park (1888); Elizabeth Taylor owned View of the Asylum and Chapel (1889); and Errol Flynn owned The Husband Is at Sea (1889). William Goetz paid what was then a huge sum for a self-portrait, but it was later exposed as a fake.