There were several dismaying aspects of the Tate’s dispute with the artist Amy Sharrocks, the latest details of which emerged in August. The Tate denies Sharrocks’s claims that it refused to allow the increasingly prominent Black artist Jade Montserrat—who makes compelling performances and drawings that possess a lyrical line and a distinctive voice—to participate in her project for Tate Exchange, Tate Modern’s community programme. It refutes any allegations of discrimination.

But it is clear that the relationship between the Tate and several artists broke down spectacularly, and that the organisation handled the situation badly. One of the story’s worrying subplots, though, was that the Exchange programme had been wound down amid the Tate’s post-pandemic review. Tate claims that Exchange was always “an open experiment to develop new ways of working”, but this seems inconsistent with how central it had seemed before Covid.

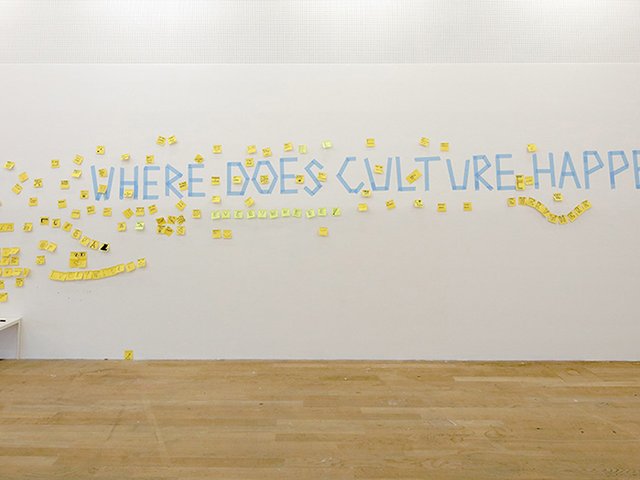

It was a progressive step museologically. Writing in the Financial Times in 2020, Tate Modern’s director Frances Morris alluded to the institution’s need to “consider art as a social space rather than as a marketplace”. Exchange allowed the organisation’s learning teams to “extend ideas of the educational, social and civic purpose of a museum”, with “collaborative, co-produced and activist” programmes, as Morris wrote. When, in 2018, the Cuban artist-activist Tania Bruguera took on the Turbine Hall project, she was also Exchange’s lead artist. It was a year after Tate named its new building after the mega-donor Len Blavatnik. Bruguera christened the part of Tate Modern across the Turbine Hall from the Blavatnik building after a local activist, Natalie Bell, effectively giving a community worker equal billing to a billionaire industrialist. That Tate embraced this gesture seemed quietly radical.

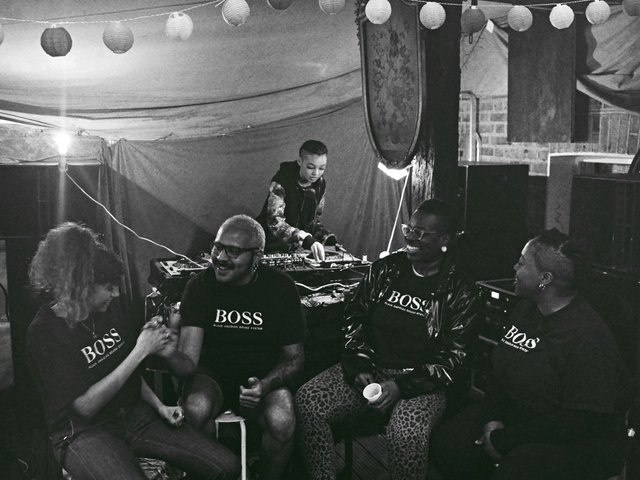

But two years later, the Tate stood accused of excluding a Black artist from its programme, even as it made statements about racial justice after George Floyd’s murder. And the corporate nature of its response did nothing to illuminate its rationale. It reflects how hard museums need to work, how flexible they need to be, to encompass increasingly influential activist communities and constituents, in addressing that “social and civic purpose”, in a period in which museums face more ethical scrutiny and financial pressure than ever.

Tate Modern’s appointment of Catherine Wood as programme director—with her impeccable record for institution-challenging work (including Bruguera’s)—bodes well, and community programmes fall within her brief. But the Tate’s reputation is undoubtedly damaged among some of the kinds of artists it hoped—and needed—to attract.