It is a cliché, especially in the UK at the moment, to say that we are living in turbulent times. As Britain exits Europe (probably, perhaps not – we don’t know yet), the new regime in Brazil, as the US president still imagines walls being built between the US and Mexico, there is political turbulence everywhere. Alongside is an expanded and often febrile social media environment and the populist polarisation of political debate. This sits hand in hand with inter-generational and identity-led clashes of values and mores – exemplified by the #Metoo campaigns, calls to decolonise collections and restitute contested objects, and increasingly confident, and multiple forms of protest, agency and creative resistance, on the part of the many who have not been at the heart of traditional power structures. Not the easiest time to be a museum Director…

In the face of this the public art museum (by which I mean an institution that has a statutory as well as a moral responsibility to be of and for the public) has a difficult, but essential role to hold open an open space for dissenting experiences of art and culture. This could entertain the utopian possibility that strangers might come together through the experience of art and agree that disagreement is possible and useful and is part of a public conversation about how we would like society to be.

So, rather than thinking that we exist in difficult times, where the liberal values of the arts are being trampled on I want to reframe our context to suggest we operate in sensitive times, where we urgently need to cultivate better listening skills and more empathetic codes of engagement. The role, therefore, of the art museum is to create a space premised on an ethics of care, for people, different views, values and realities and on expanding the practices by which people can engage with art. If we can do this, we do justice to the nuance and complexity of art practice and we also open up our spaces and histories to more than one story, view or idea. We could, if we take care, become the many.

But there is significant challenge here, because it should require us to go to the places and hear the ideas and views of those who do not want us, not only those who like us already, or are open to the idea that art could mean something to them. So we can’t only see ourselves as the progressive guardians of all that is good and uplifting in a morally corrupt world. We are, of course, part of the problem and we need to openly explore the profound exclusions and disagreements with us, that result in the societal polarisation of the Brexit vote or the Brazilan elections. And without losing our own values, we need to hear the many other sides, because now more than ever we need to nurture spaces where disagreement, complexity and uncomfortableness can be constructively examined. Otherwise, we fail to hold to the most useful thing about art, which is that it is fundamentally subjective and ambiguous.

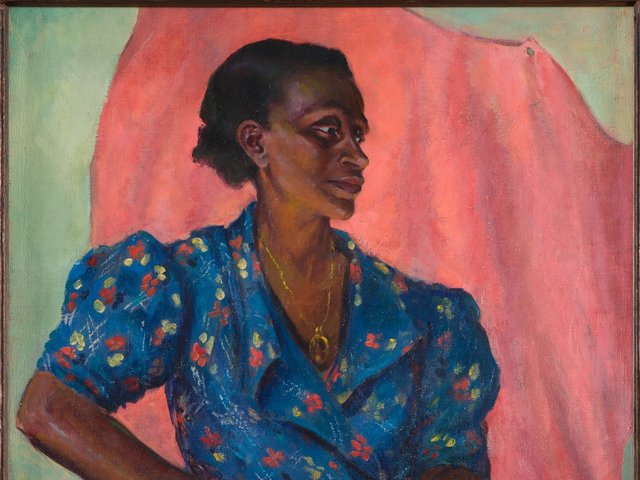

I came to Tate a little less than two years ago, inheriting an expanded institution that had been led by one of the most influential museum Directors of our time. Under Nick’s leadership, Tate’s expansions changed the art world. For the UK this meant making contemporary art part of daily public life – more than 8 million people come to the Tates, and millions more engage with us globally online and through our exhibitions worldwide. And I would argue, it has made art seem less elite and more conscious of its role in shaping the public sphere and public opinion. Your Verbier Art Summit speaker of last year Olafur Eliasson achieved that when the public took on the role of ‘activating’ his Weather Project, and Tania Bruguera (one of this year’s speaker at the Summit) carries that baton now, as her Turbine Hall implements a new and different community of Tate neighbours (and I am glad to hear she sees us an organisation open to change). Tate also chose to change the art histories to told, to become less white and western, regendering the canon and focusing on other centres of art that have emerged across the globe through the 20th and 21st century. This is a key part of our future as we explore the meanings of historic collections formed through imperial might in a contemporary, post-colonial world, and the way art and artists shape debates about identity, power and the politics of culture.

© Tate photography

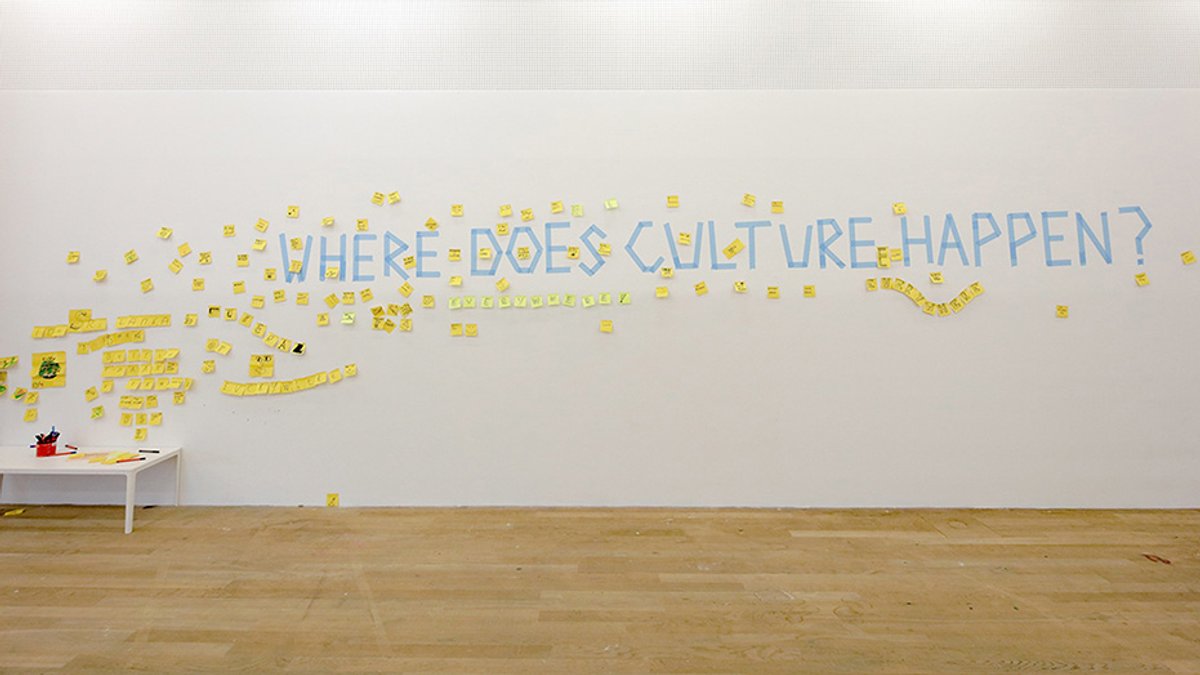

In all this, the significance of art for people, who gets to make it and who gets to shape the meanings we attach to it is a critical question - one we have recently been exploring with the public in Tate Exchange, which has been unfolding as an idea and a practice for nearly 3 years now at TM and TL. It began with an idea about the Tate Modern building but has rapidly become a project about transforming people’s relationship to art, artists and to us as a national institution. I might even venture that it is an ongoing experiment in changing us as an institution. Tate Exchange was set up to explore and design new ways to engage a more diverse public with Tate’s collection. It aimed to generate debate around ideas in art that are relevant to issues today and was constructed as a platform (in-gallery and online) on which other organisations, as well as Tate, might undertake this work. So it involves developing new practices, languages and ideas within the space of the museum.

The ‘other’ organisations are known as Associates. There are now 25 at Tate Liverpool and 63 at Tate Modern. These range from small arts charities such as Museum of Homelessness, or the black artist collective Thick/er Black Lines to very large organisations, such as the University of Plymouth or the Royal College of Art. Importantly, many of the Associates are not from London, so it is an exercise in hearing across our country right now. The structure is relatively simple, the diverse group of Associates work with us to define a theme for a year and to select a ‘lead artist’; to work with many of the partners (in the year past, it has been Tania). Each Associates brings their ideas, their practices and their constituencies. This has been vital in shifting who comes to Tate, and who has a stake in making and shaping ideas in the organisation. Over 500,000 people have taken part in Tate Exchange, with many more participating online. The Exchange ethos prompts new ways of working to encourage public involvement, action, interaction and dialogue. This is sometimes joyful, often critical, but always ’a deeper dig’ into what we can become, together. And it is where we are learning to be open to critique, and not too sensitive about it.

The examples emerging from Tate exchange explore the integration of our social and artistic mission, they meet the requirements of our public funding, and also represent major opportunities in maintaining our audience levels, and our relevance to funders – public and private. It is the key to our future relevance and sustainability. So, my vision for all of the Tates – as a distributed national collection and a globally connected and locally relevant institution – is that we should be open, generous and connected. I am looking forward to seeing how through being open to the disagreements and critiques that emerge in and through Exchange thinking we can make greater impact on our city and the world we are in.

Doing this should allow us to shift the demographics of those who typically come to art galleries, toward being more inclusive of those who are not the ‘invisible white norm’. This also means we need to become a more diverse organization internally. This is easy to say and difficult to achieve, at least at first, so we are challenging ourselves and have to be open to changing ourselves and doing so at a very contested time. As a colleague recently said to me ‘these past 12 months, it is as if someone has had their finger on the fast forward button’. I think she is right, I find it very exciting, much of this cultural challenge about power and authority is what I have wished for my whole life.

We, in the cultural sector, have no other option to be in it. It is our terrain. Imagining the ‘fast forward’ button is also, of course, a gorgeously analogue metaphor for our times as you have to be my age or older to connect to the speeded up sound of fast forwarding through a song you don’t like on your tape recorder. My kids don’t know what I’m talking about. So it marks us out as a bit old too and we do well to remember this as well, because my generation began life in an analogue world and we lead now in a digital one, so we need expertise from the generations who follow us to understand what this mean for the arts.

And even as I welcome the radical shifts in cultural authority and want to support them, they have also been immensely challenging for me at the helm of Tate and are, I think, for any leader now. And I want to share this, as I feel otherwise I will not be living up to the honesty and self-examination that good leadership demands. It’s hard because it means putting our head above the parapet and really beginning to address issues of power, privilege and control. Most leaders of national cultural institutions just now, however radical their own background, or sincere their commitment to changing who these organisations speak for or to, are likely to encounter some ‘but you too are part of the problem’. Certainly, I have, and it felt very strange being accused of being ‘part of the establishment’ when I feel most of my career has been in opposition to this. But it is no good to say defensively, ‘look at my track record’; instead, I think we have to say, ‘we want to be part of this dialogue, we have knowledge to share here, and what do we want to change, what does an art gallery need to do, what can I do differently as a leader?’. This is part of working toward more representative and inclusive ‘national cultural institutions’. As Tristram Hunt, Director of the V&A wrote last year, museums are not straightforwardly political tools, but we do need to be ‘safe spaces to explore unsafe ideas’.

To do this requires leadership with and through empathy, and this can feel very hard across 1200 or so people, with the triple challenges of commerce, cultural and artistic purpose and communities of stakeholders, whose needs and wishes will rarely ever clearly align. This is about leadership in the context of uncertainty. Focus, clarity, vision – the key attributes of classic leadership – are actually about being single-minded and this is not a very good thing if you want to lead in the context of complexity and wish for a multiplicity of voices, people and stories to emerge. Vulnerability is hard to hold to as a leadership value but I think it is an essential aspect of accepting that any organisation, might not have all the right answers, nor will it always do the right things, but that stepping into an uncomfortable, risky place, where failure is embraced as part of learning and eventually becoming successful, is not only important it is non-negotiable if we are to be of our times.

In the arts, more than anywhere, we must create a larger space to think, act and dream differently. Because this is what underpins all the art we are all engaged in.

This article is taken from a key note speech delivered by Maria Balshaw at the 2019 Verbier Art Summit, Switzerland.

The 2019 Summit publication is the outcome of the 2019 Verbier Art Summit held 1 & 2 February 2019. For more information and memberships, please visit: www.verbierartsummit.org