The Royal Academy Summer Exhibition has just opened, that annual jamboree of popular curiosity and critical ridicule. This year’s edition is focused on climate and for Alison Wilding RA, the co-ordinator this summer, that issue is a “huge all-embracing… subject”. On that, it’s hard to disagree. Many of the artists represented desperately want to call action on the climate crisis but end up appearing polite and tame, rehashing the staid clichés of the earth as either a house on fire or a benevolent mother, while rarely confronting the extant reality of “extreme” weather events in the Global South or ecological horrors wrought by mundane elite consumption.

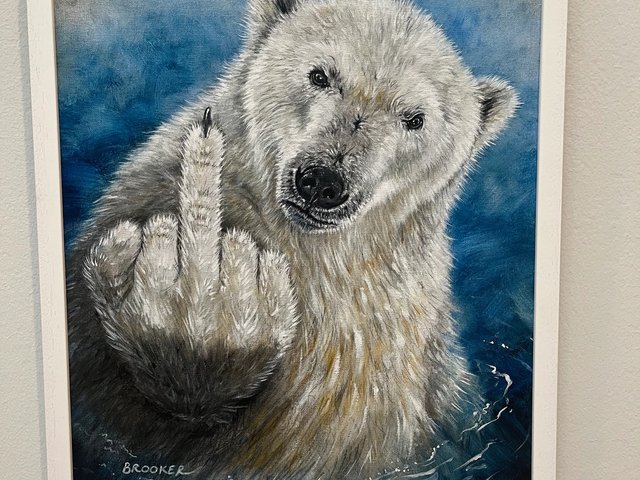

Unfortunately, we don’t need climate change to be any more shocking or provocative or incendiary than it is already; we need art to be more truthful, and to help make sense of such an ungovernable threat. It’s hard to see how we need an oil painting of a polar bear shoulder-deep in Arctic water giving us lot the finger, as we have in Gallery VI, to elicit outrage with the most urgent issue of our times. We don’t need the earth as a blazing ball of fire careering towards a toddler eating an ice cream. Let’s not pretend that this task is easy, and all agree that climate change as something that we might be able to study and compute but not directly see does not always lend itself to a coherent art. But when the Academicians cut through to present works that are palpably more truthful to the lived experience of climate change, especially in photography and video, and especially when artists think of the world as it is and not flaccidly forewarn what it might be, this exhibition does far more for those noble ambitions than a tired placard.

"An icon for sunshine and thunderstorms seems to warn us that 'there will be variable weather'—and little else." Photo: © David Parry/ Royal Academy of Arts

Text-based art and recycled media images play an oversized role here, with glib provocations like “NO ONE REALLY UNDERSTANDS CRYPTO”, which might feel timely as bitcoin nosedives if it wasn’t so painfully easy to figure out and didn’t look like it was doodled on MS Paint in Windows 7 (but maybe that’s its lo-fi medium-as-message). Like the schematic stock images that you see hovering over a map on BBC Weather, an icon for sunshine and thunderstorms seems to warn us that “there will be variable weather”—and little else. Even the venerated Bill Woodrow mistakes language play for banality when he takes the found object of a “Flood” roadside sign and smothers two red crescents on the first letter to spell “Blood”. Do you get it? At £25,000, it’s one of the most expensive pieces in the show.

That’s not to say that language can’t be used thoughtfully when engaging with the dire experience of how extreme climatic conditions affect everything from air quality to home insurance to seasonal produce availability. Rose Wiley’s characterful Out Now series (2022) announces the arrival of plants like cow parsley and japonica on 5 February, about three months earlier than the usual natural cycle. It’s the evidence of an ecology in turmoil that Queen Anne’s lace is flowering in late winter, but Wiley takes aim at how we delight in it rather than feel horrified. This artist’s looping scrawls land on the right side of writerly wit and show how text can be a visually arresting element in oil paint.

Grayson Perry’s End of Covid Bell © David Parry/ Royal Academy of Arts

Writing in the Guardian, Jonathan Jones derided the exhibition for being little more than Tory greenwashing: “climate kitsch”, which is “as concerned for the environment as Boris and Carrie Johnson”. The comment on kitsch might ring truer than Grayson Perry’s wincingly bad End of Covid Bell (2021), and it’s almost certainly the case that a serious institution has never displayed so many slogan-based daubs that belong on a fridge magnet (or an XR sticker). Or, for that matter, so many works of animals dressed as humans. A slouching badger performing Hamlet’s “To be or not to be” soliloquy with a skull was my personal favourite, although quite what this has to do with the climate remains elusive.

The curators seem to have bought wholesale into the ‘kids are alright’ mentality

Liberal self-flagellation

But the trouble with this Summer Exhibition is that it’s been curated as a very liberal show. It betrays much about the failures of liberal, middle-class society to take the climate crisis seriously. There’s everything here to cohere an atmosphere of a self-flagellating yet self-satisfied liberalism in works that reveal a perverse nostalgia for the arcadian land before human habitation, or the fetishisation of naïve art and art made by schoolchildren. Rather than make space for a new generation, the curators seem to have bought wholesale into the “kids are alright” mentality of today’s eco-politics: let young people imagine apocalyptical futures while we abdicate responsibility to address the world as it might be and not as it is for those who suffer climate extremities the most.

With all of that said, there are nearly 1,500 works here. Sheffield-based Special Olympian and artist Niall Guite has made some stellar drawings of stadiums, including a version of the plans for Eco Park, the new home of “greenest football club in the world”, Forest Green Rovers in Stroud. These drawings are an effective counterbalance to screen-printed football flags in the entrance that ask what would happen if we showed as much support for climate policies as we do for our football teams. “Forest Fires” is figured on the logo of Nottingham Forest; Manchester City’s crest is flooded in baby-blue water as its signature golden vessel sinks into the Ship Canal. The logic might be sound, but it feels somehow classist as a thought experiment to say that heedless football fans are the ones we should be outing for blame.

The most compelling works are easily those that forgo smug sloganeering to confront specific touchstones of the climate emergency in a humane way, often through photography and video art. Interpretation before learning feels indulgent at this moment—we aren’t there yet—and there’s something far more compelling in the way that many artists here engage with specific flashpoints and coherent symbolism that refuses to be overwhelmed by the sheer impossibility of representing the climate writ large. Edward Burtynsky’s photograph of the Dandora landfill in Nairobi depicts the inconvenient truth of global plastics recycling on the world’s poorest today, and not in a deferred future. Antonina Mamzenko renders a moment of thalassotherapy, or a sea cleanse, from above that half drowns the subject in its own individualistic purification process.

Uta Kögelsberger, an artist and professor at Newcastle University, received the Charles Wollaston Award for her video Cull (2020-present), a five-channel installation that follows the clean-up project after the 2020 California Castle wildfire destroyed 174,000 acres of the Sequoia National Forest. It’s a towering and compelling work. As charred and lifeless trees threaten the structures around them, tree surgeons cut them down one by one in a sequence that resembles the moment of death at the hands of a firing squad. Cull is a haunting work that, while refusing to aestheticise the death of the world’s forests in slow motion, leaves such a lasting impression as to feel as though we had touched and known those felled trees.

John Gerrard’s Western Flag (Spindletop, Texas) (2017) is featured in the Lecture Room and depicts the site of the “Lucas Gusher”—the first major find of the Texas oil boom in 1901—which is now sterile and uncultivable. Gerrard has recreated the site as a digital simulation and depicts a flagpole that endlessly renews pressurised black smoke like the stripes of the American flag. As our frontal perspective moves 360 degrees around the axis of the flag, the visceral truth of the co-implication of state formation and fossil fuels is powerfully puffed out into the atmosphere.

The Summer Exhibition should offer so much promise, in the craftsmanship of its content and the ideas of its contributors, but instead too often falls for the obvious over the intelligent. The public deserves to be confronted with the facts of climate change in art that is bold enough to square up to its complexities.

• Summer Exhibition 2022, The Royal Academy of Arts, London, until 21 August

• Exhibition co-ordinator: Alison Wilding

• Matthew Holman is a lecturer in English at University College London