As America marks two years since the murder of George Floyd, the director of a leading US institution has called on the museum sector in the US and beyond to “confront the colonial narratives we have inherited”.

Thomas P. Campbell, the director of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco (FAMSF), told The Art Newspaper in an interview that US museums “all too often uphold colonial narratives in our galleries”. Campbell, a former director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, made the comments as the FAMSF announced the appointment of a new director of interpretation.

Abram Jackson, a former adjunct professor at San Francisco State University, is the first incumbent of the new position.

In an interview, Jackson said his role was to look at the museum’s collection “through an equity lens”. Doing so, he says, “will help to welcome patrons who may otherwise feel rejected, triggered or concerned about their experience at the museum”.

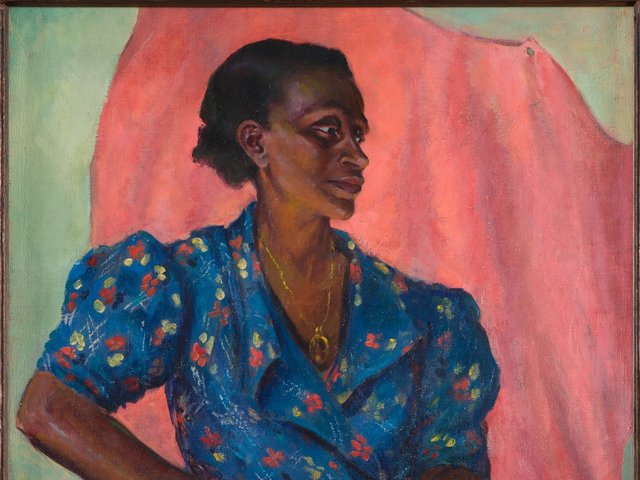

Fashion designer Patrick Kelly, who appropriates racist imagery, such as the golliwog, in his work Frederic Reglain/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images

Jackson will spend much of his time working out how to frame art from the museum collection that may have colonialist roots. He will also, he says, explore how the artistic reappropriation of racist insignia can best be communicated in museum settings, noting that the pop artist Kanye West co-opted the Confederate flag on a tour promoting the 2013 Yeezus album, which included the song New Slaves. He also cites Patrick Kelly, the first Black American fashion designer to sign a multimillion-dollar fashion deal, who has often incorporated into his designs racist symbols like the golliwog.

If there’s any space in the world where we can make sense of a text or work that might have a racist context, it’s in a museumAbram Jackson, director of interpretation

“Museums are sacred spaces,” Jackson says. “If there’s any place in the world where we can make sense of a text or work that might have a racist context, it’s in a museum.”

His role will not be easy. His colleagues at London’s Tate Britain recently welcomed criticism they received for their distinct framing of the satirical paintings of William Hogarth, the 18th-century artist who depicted scenes that may be considered problematic from today’s perspective. One prominent UK critic said the Tate exhibition was “wokeish drivel” which “yanked [Hogarth] into today’s culture wars”.

Problematic history

“Museums have a really problematic history, to be frank,” Jackson says in response. “But you can use this idea. It helps us to think about what patrons need, in all their differences.”

Jackson may be the first director of interpretation in San Francisco, but other museums look set to follow suit. Last month marked two years since George Floyd was killed in police custody in Minneapolis. The huge social unrest and structural shifts the murder prompted continue to reverberate; increasingly, the disparate conversations the murder instigated are morphing to into sweeping and lasting policy changes across the public sector.

“The George Floyd moment, for better or worse, put the rubber to the road for a lot of institutions,” Jackson says. “It led many museums to rethink their whole approach on things like hires, roles and policy. It wasn’t just a reflective moment. I think it impacted our collective consciousness and allowed us to think about how race and racism impacts all of us—and what institutions can do to shift that.”

Last month, the Smithsonian Institution announced it will adopt a revised restitution policy. In the past, museums have leant on legal precedents to determine if, how and when items from their collection were repatriated to the original holder. Now the Smithsonian says restitution cases will be based primarily around ethical considerations, rather than legal ones.

The new policy will formally allow the Smithsonian’s constituent museums to easily and proactively return items from their collections that are known to be stolen, looted or acquired by underhand means. Notably, the overarching policy, which falls under “collections management” rules, was adopted by the institution after a sustained process of internal consultations with Smithsonian curators and collections specialists.

Beyond the Smithsonian, numerous other high-profile museums in the US have incorporated sweeping decolonisation initiatives into their publicly viewable strategic plans, including the Abbe Museum in Bar Harbour, Maine, and San Diego’s Museum of Us, which is located on the ancestral homelands of the Kumeyaay Nation.

Beyond the US, the Australian Museums and Galleries Association is in the midst of a ten-year Indigenous Roadmap project. The Musée d’Ethnographie de Genève, in Switzerland, has set itself the target to decolonise the museum entirely by 2024. And the Pitt Rivers Museum, part of the University of Oxford, announced in 2020 an “internal review of displays and programming from an ethical perspective”.

The review has already led to the removal from view of the Shuar Tsantsa—the museum’s collection of so-called shrunken heads, which are considered sacred by the indigenous Shuar and Achuar peoples of Ecuador. They were once lauded as one of the museum’s most sought-after displays.