Is it possible to experience a sense of belonging in spaces—and with objects—not made for you or with you in mind?

As a Black feminist curator, one of my core concerns is how the collections and galleries within my purview and care might be a place of enjoyment and belonging for Black women specifically. If it is recognised that museums are vehicles of social belonging, then everything from how information is presented to how spaces are staged and how works are installed within specific parameters of style and taste are all acts of power that set the terms for this sense of connection.

It is from this understanding that I urge collecting institutions to reassess the chokehold that antiquated “master” narratives have on their displays, and I propose redesigned collection spaces that offer unique alternatives to traditional displays of American art—alternatives that are creative, inclusive and invite joy.

There is a critical wave of thought-leaders charting new paths while also applying pressure to the field of art history and museums, calling on institutions to assess themselves transparently and make changes that align with their stated missions and visions of diversity, equity and inclusion. Their work has led to advisory councils, convenings, dozens of reinstalled collection spaces, community partnerships, special exhibitions, audience surveys and focus groups, publications, roundtables and millions of dollars in grants towards these efforts.

At the Brooklyn Museum, we are unflinchingly taking up the collections we have, pushing the boundaries of representation by framing a largely white and canonical American art collection through the cultural contributions, lenses and critical sensibilities of non-white communities. One example is our study of the Hodinöhsö:ni’ (Haudenosaunee) Thanksgiving Address. Spoken by members of the Hodinöhsö:ni’ Confederacy, it establishes gratitude as the highest priority and reminds us that the abundance of our world provides everything we need. The museum also uses concepts like rematriation—considering our responsibilities and relationships to the land, our belongings and each other—to inspire and inform our research, display and care of works that relate to the land or our sense of place.

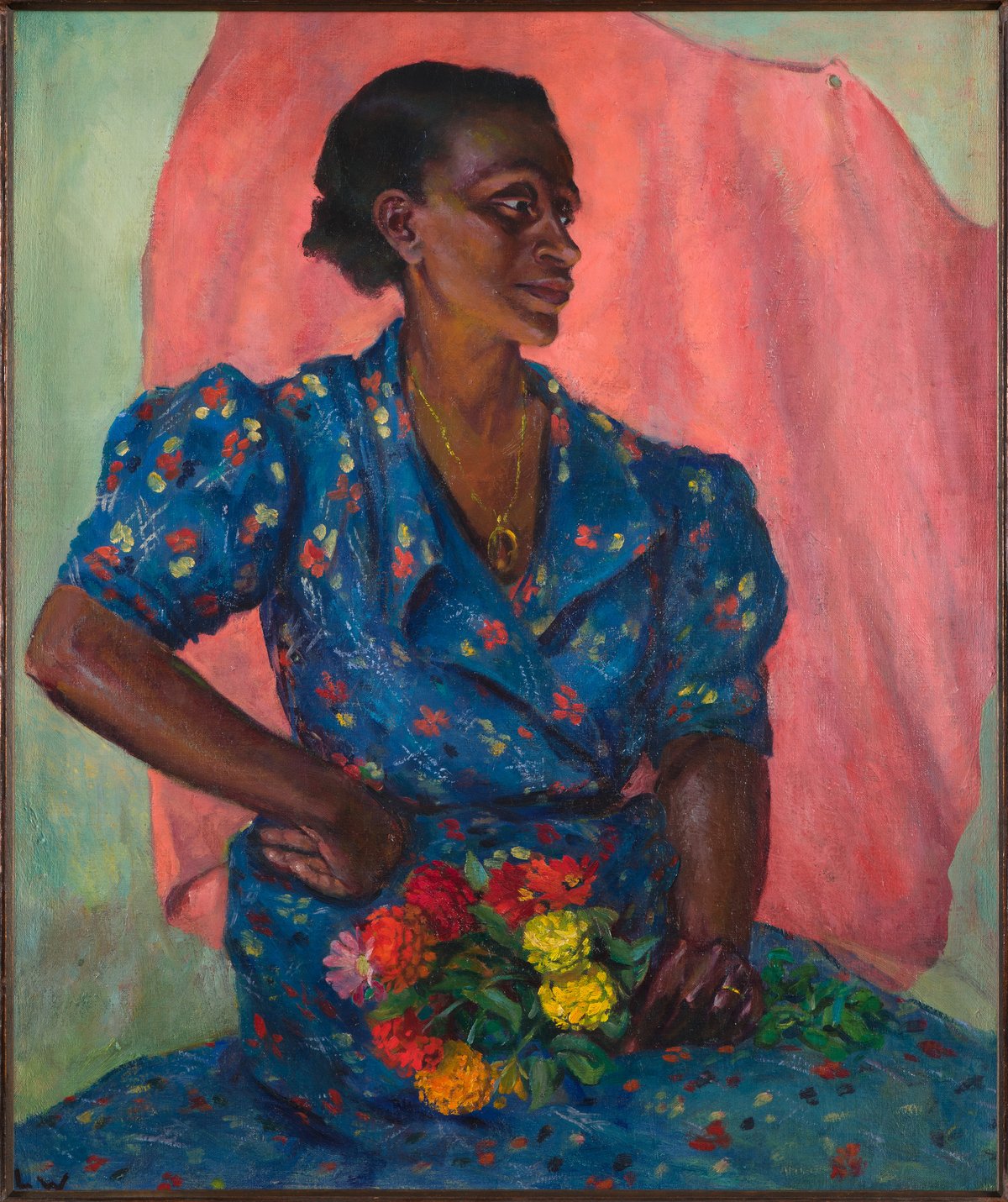

Installation view of Toward Joy: New Frameworks for American Art, Brooklyn Museum Photo: Thomas Barrett, courtesy the Brooklyn Museum

The collections reimagined

Moving away from approaches that merely “add and stir” historically excluded art and creative traditions into a set of canonical narratives, the Brooklyn Museum is exploring new paths forward in research, interpretation and care for collections that are inspired by the ways strategically undervalued communities see and experience the world. For example, we are framing an entire cross-section of the museum’s collection—namely, works with floral symbolism or related material significance, such as botanically derived fibres or dyes—through the Black vernacular adage “to give someone their flowers”. (Emerging from Black American funerary and gospel traditions, this saying encourages listeners to “give flowers” while the recipient can “smell them”, asserting the importance of giving people their due while they are still around to receive it.) The space is filled with a floral wallpaper designed by Loïs Mailou Jones, and interpretation is enhanced by staff at the neighbouring Brooklyn Botanic Garden. Every layer from the checklist to the design, research, wall text and colourful juxtapositions is aimed at sparking recognition and joy.

Regarding this powerful kind of reorientation in representation, the curators Janet Dees, of the Block Museum of Art at Northwestern University in Illinois, and Alisa Swindell, of the Hood Museum of Art at Dartmouth College in New Hampshire, individually and collaboratively explore “what it means to proliferate an abundance of Black feminist ideas and aesthetics into the institutional fabric of art history and museums”. In a jointly written chapter of the forthcoming book Reenvisioning Histories of American Art, Dees and Swindell ask: “Might these institutions feel less obsolete if we accept the work of Black feminism as an urgent task—not just increased representation of Black women in museums, but a fundamental shift of material circumstances?”

Installation view of Toward Joy: New Frameworks for American Art, Brooklyn Museum Photo: Paula Abreu PIta, courtesy the Brooklyn Museum

A place for everyone

Part of what makes Black feminist thought, work and practice so innovative is the way they draw upon the lived experiences of the most marginalised to chart new possibilities that uplift and support those very individuals. However, Black feminist application or methodology is not only about centring people who identify as Black women. Rather, it imagines and articulates a just world where everyone has a place and what is needed to thrive, which, in this sociopolitical climate, is a model worth pursuing.

Black feminism encourages us to be creative about what we decide to accept or not. In fact, interpretation is an ongoing project, and we can and should introduce different terms. In doing this work, we can influence the creation of galleries, institutions, cultures and worlds in such a way that belonging becomes capacious and not solely dependent on one’s proximity to whiteness, Western values or art-historical tropes.

Undoubtedly, attempts to reorient a historical American art display through a proliferation of Black feminist aesthetics, ideas and approaches come with inevitable risks. These risks range from the loss of financial support and racist backlash to the possibility of audience discomfort and criticism as people encounter unfamiliar ideas that challenge their expectations. My firm belief is that these are risks worth taking.

- Stephanie Sparling Williams is the curator of American art at the Brooklyn Museum

- Toward Joy: New Frameworks for American Art, Brooklyn Museum, ongoing