It is now 20 years since a trove of Polaroids, documents and antiquities that passed through the hands of the convicted dealer Giacomo Medici were discovered in a Geneva Freeport, seized by the Italian police and presented as evidence in a high-profile looting case in Italy. Six years later, in 2001, the more detailed archives of another convicted antiquities dealer, Gianfranco Becchina, were retrieved by the Swiss authorities and then transferred to Italy.

This led to a number of court cases surrounding illegally-excavated antiquities and resulted in some convictions, but no jail time, due in part to statutes of limitations expiring in Italy (see below). They have also embroiled Medici and Becchina’s suppliers and buyers—notoriously including the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles—with the Becchina archive’s contents leading to police investigations of 10,000 people’s affairs in Italy alone.

Only a small portion of the looted works that feature in the Medici and Becchina pictures have been identified, and the raids have had a profound effect on the trade in antiquities. Some items have been repatriated—in May, the US authorities returned 25 pieces, many allegedly sold by Medici and Becchina, back to Italy. These included three frescoes stolen from Pompeii in 1957 and a Roman sarcophagus lid that had been on the market for $4m.

However, museums, auction houses, dealers and most other intermediaries are still in the dark about the tens of thousands of likely illicitly-plundered items included in these, and related, archives, the contents of which are known only to a few.

A call for transparency

The calls to make the archives more widely available have grown louder in recent months. In March, the influential Association of Art Museum Directors (AAMD), which has 237 members from the US, Canada and Mexico, issued a statement on the proposed renewal of the Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) between Italy and the US on protecting cultural property (due for renewal in January 2016). Among the issues raised by the AAMD is that “the MOU should be amended to encourage Italy to make the contents of the Becchina and other dossiers readily available to the general public unless…widespread disclosure would compromise an existing criminal investigation or claim.” The association goes on to describe museums as being in a “Catch-22” situation: “To be blamed by Italy, the press and others for owning objects with provenance issues, while simultaneously denied the ability to confirm whether those objects passed through the hands of these dealers.”

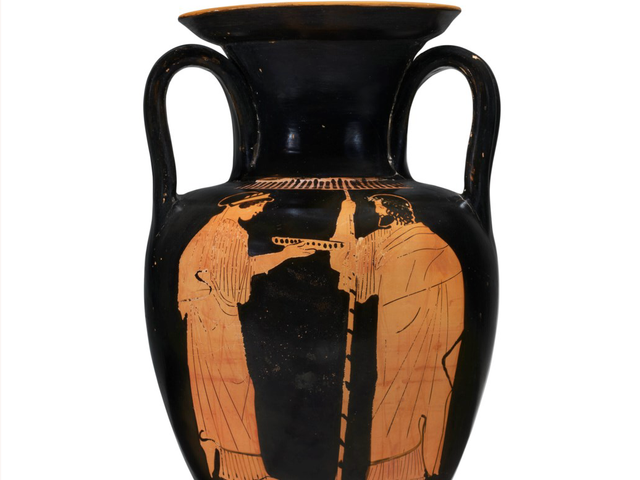

Meanwhile, pieces keep appearing in auction catalogues that are subsequently shown to have links to one or more of the archives and—often to the embarrassment of the auction houses and the dealers who may have handled them—then have to be publicly pulled from sale. In April, Christie’s had to withdraw four artefacts, including an Attic black-figure vase from around 530BC which had an estimate of £50,000 to £70,000.

The archives are understood to be with the authorities in Rome. In April, Ilaria Borletti-Buitoni, Italy’s junior minister for culture, was asked (at a “Culture in Crisis” conference in London) what the ministry’s position was on making them public, to which she answered: “I’ve no idea [of] the position of the minister—forgive me because we haven’t discussed the matter. But I suppose [his] position could be to make these archives open. I suppose.” A spokesman for the ministry since referred all questions about the archives to the Carabinieri art squad, a branch of Italy’s military police. The Carabinieri did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

Whose archives are they anyway?

One unanswered question surrounds the ownership of the archives, a possible block to making them more public. Italy’s Ministry of Culture is said to have the legal rights to the archives, though a spokesman did not confirm this.

Others say that Medici and Becchina, who are still alive, arguably own the copyright to the images and notes that they made. Medici has previously said that eventually his archives will have to be returned to him. He did not respond to our questions directly for this article, but says that the final judgment on his case “states that the crime does not exist”. (His trafficking conviction was dismissed because the statute of limitations had expired; he lost his final appeal against his other convictions.) Medici referred us to the Carabinieri, but it also failed to respond.

Notwithstanding their legal status, the information within the archives seems to be being shared selectively, further fuelling the age-old mistrust between archaeologists and the trade. One person who certainly has access is the UK-based Greek forensic archaeologist Christos Tsirogiannis, a research assistant at the Trafficking Culture project at the University of Glasgow who is officially appointed by Greece's public prosecutor. In this capacity, Tsirogiannis has, since 2006, been responsible for identifying the antiquities in museums, collections, galleries and auction houses that are in the confiscated Medici and Becchina archives, and related Symes-Michaelides ones (see below), work that he says he does for free. As well as notifying Italy’s public prosecutor and the Greek authorities (among others), Tsirogiannis does not shy away from releasing his information more widely, often resulting in public disagreements with the auction houses or dealers involved.

Tsirogiannis believes that the bulk of the objects covered by the Becchina, Medici and Symes-Michaelides archives (which he says could number more than 100,000) were illicitly obtained. But in his view there is a simple solution: “It is well known that the Italian and Greek authorities [whom he says share the information] hold the copies of the archives so whoever wants to check an item should just send a photograph of it to these authorities before their catalogues are put together.”

Many in the trade say that such an approach is impractical and naive. In a statement, Christie’s says: “We have in the past sent individual queries to the Carabinieri but they have not responded. We are, of course, continuing actively to try to explore this route both with the Greek and Italian authorities as well as through other avenues… We are asking for access and full transparency for us but also for the art market as a whole.” Greece’s ministry of culture also did not respond to requests to comment.

Further muddying the waters, one private firm also now seems to be in on the act. Chris Marinello, who runs the Art Claim Database at Art Recovery International, is known to have gained access to the Medici and Becchina archives this year. How he is getting this information remains a mystery—Marinello says he cannot comment as revealing his sources would challenge the “integrity of the database”—but he is said to have matched an item for an auction house this year.

His competitor, James Ratcliffe, the director of recoveries and general counsel for the Art Loss Register, says: “We have asked the Carabinieri repeatedly for access but not got anywhere.” Even Marinello—who seems now to have a competitive advantage—has said that the archives should be made public.

Cleaned-up trade

Meanwhile, those in the antiquities trade do not shy away from the fact that they have a reputational issue to address, not least given the actions of Medici, Becchina and their circle, but are keen to show that they have moved on.

“The market has been buccaneering and had its own laws, which were clearly quite wrong, but it has changed enormously,” says James Ede, a London-based antiquities dealer. He founded the International Association of Dealers in Ancient Art in 1993, largely to maintain high ethical standards internationally (32 members have been accepted so far). “We [in the trade] would like more information to be shared with us, it is not in our interest to fall foul of any laws. We are more than willing to take part in any

constructive and open discussions,” says Joanna van der Lande, an antiquities consultant.

Some key players • The dealer Giacomo Medici’s warehouses were raided in 1995 and he was convicted in 2004 of receiving stolen goods, illegal exports of goods and conspiracy to traffic. He was sentenced to ten years in prison and received a €10m fine. In 2009, a Rome appeal court dismissed his trafficking conviction (because the statute of limitations had expired) although the other charges were upheld. His sentence was reduced to eight years. In 2011, his final appeal failed and Medici asked to remain under house arrest due to his age (he is 76) and ill health.

• In 2011, Gianfranco Becchina, a dealer in Switzerland who is from Sicily, was found guilty by a court in Rome of illicitly dealing in antiquities, a conviction that he is appealing. Other criminal charges against Becchina—including for smuggling and receiving stolen goods—have expired under a ten-year statute of limitations. Investigations into Becchina began in 1992, and continue today. Earlier this year the Carabinieri seized 5,000 antiquities in Switzerland that were linked to Becchina.

• Italian prosecutors argued that Robin Symes, a British antiquities dealer, was the frontman, alongside Medici and Robert Hecht (see below), but was never charged and has denied that he knowingly sold looted goods. An archive of photographs of works traded through Symes and his partner Christo Michaelides was seized at a villa on Schinoussa, a Greek island, in 2006. Michaelides died in 1999. Symes has served prison time, in 2005, for contempt of court in an unrelated case.

• Marion True, the former curator of antiquities at the J.Paul Getty Museum, was charged in 2005 and tried in Italy and Greece on offences relating to antiquities smuggling. The case against True collapsed in October 2010 in Rome, when the statute of limitations for her alleged offences expired.

• The American antiquities dealer Robert Hecht was charged alongside True and Medici of conspiring to receive antiquities that had been illegally excavated and exported from Italy. Hecht’s trial ended in 2011 without a verdict, and he died in 2012, aged 92.