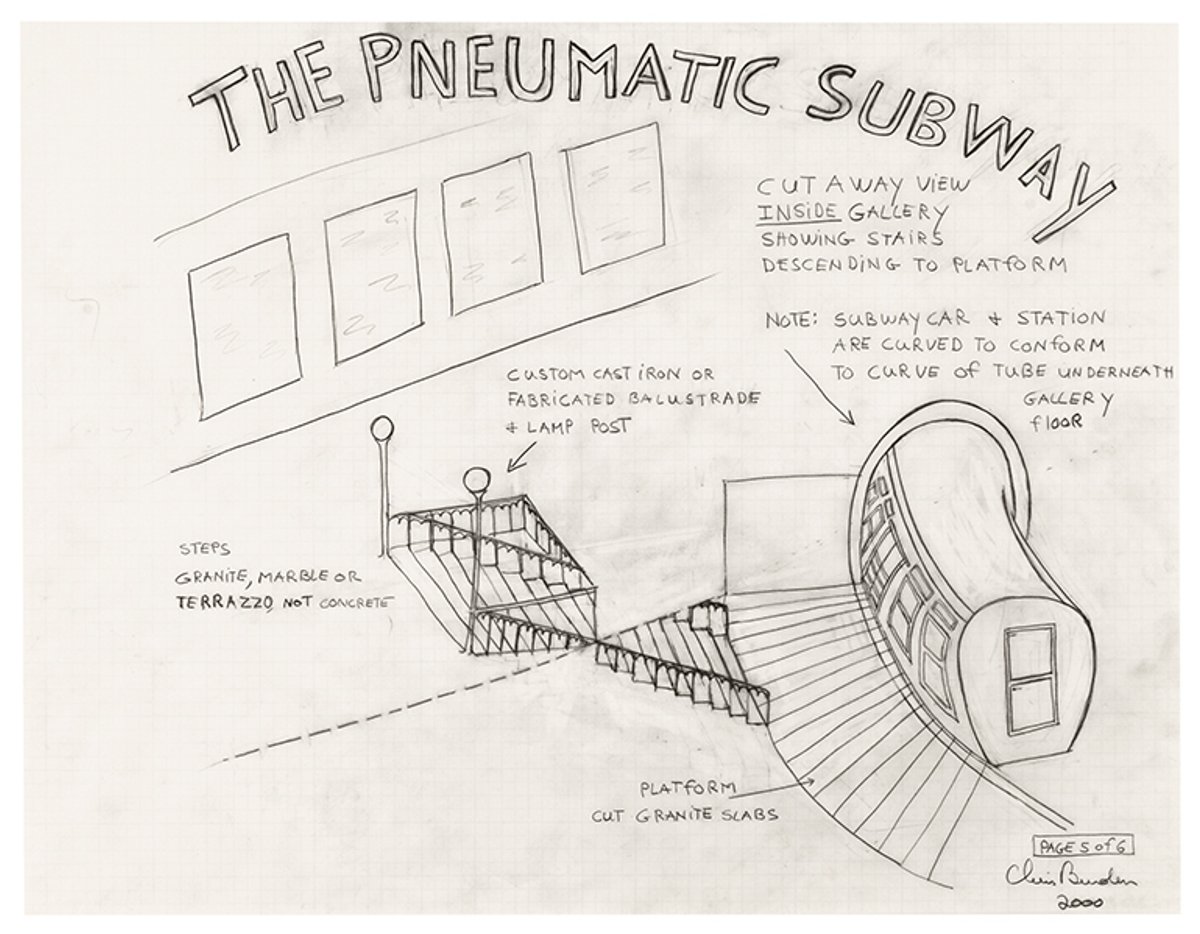

Shortly after Gagosian opened its flagship gallery on West 24th Street in New York in 1999, Chris Burden proposed a show there using the entire space. Above ground, he envisioned two giant kinetic sculptures. Below, he wanted to dig a tunnel to create what he called The Pneumatic Subway. A subway car, fitted in a tight tube, was meant to carry up to 20 people at a time in circles. The subway entrance would be marked in the gallery by a cast-iron balustrade and lamp post—an early sign of his interest in street lamps.

Burden was the first artist Larry Gagosian ever represented, going back to his 1976 show Relics in Los Angeles. (That show included the lock from Burden’s famous performance Five Day Locker Piece, which Gagosian still owns, and the bullet from Shoot, which Jasper Johns owns.) But digging underneath the New York gallery was not an easy ask, especially given that its electrical and mechanical systems are located underground. His pneumatic subway was never built.

“We did manage to make Fist of Light, which we presented at the Whitney and which was an insane piece,” says Gagosian, who notes that he always liked Burden’s bluntness. “He was extremely intense, just all-in,” he says. “But the subway was a tough one, just complicated to realise.”

Unorthodox ideas

And it was far from the only unrealised proposal in Burden’s archives when he died in 2015. The artist left behind an “extensive” and “highly organised paper and object archive”, says Yayoi Shionoiri, executive director of his estate. Now, drawing on this archive, Gagosian is publishing a book presenting 67 unrealised projects, complete with sketches and notes by the artist that reflect his unorthodox, and sometimes subversive, application of scientific research. The entries are organised by core themes: energy, systems, architecture and power.

Some of the projects seem familiar—variations on the bridges and skyscrapers he built over the years with vintage Erector or Meccano parts or stainless steel reproductions. There is also a never-attempted Beam Drop, a 2008 plan to drop three steel I-beams through the ceiling of mega-collector Michael Ovitz’s home gallery in Beverly Hills (and then reseal the roof), which was serious enough that the two spoke about it as late as 2013.

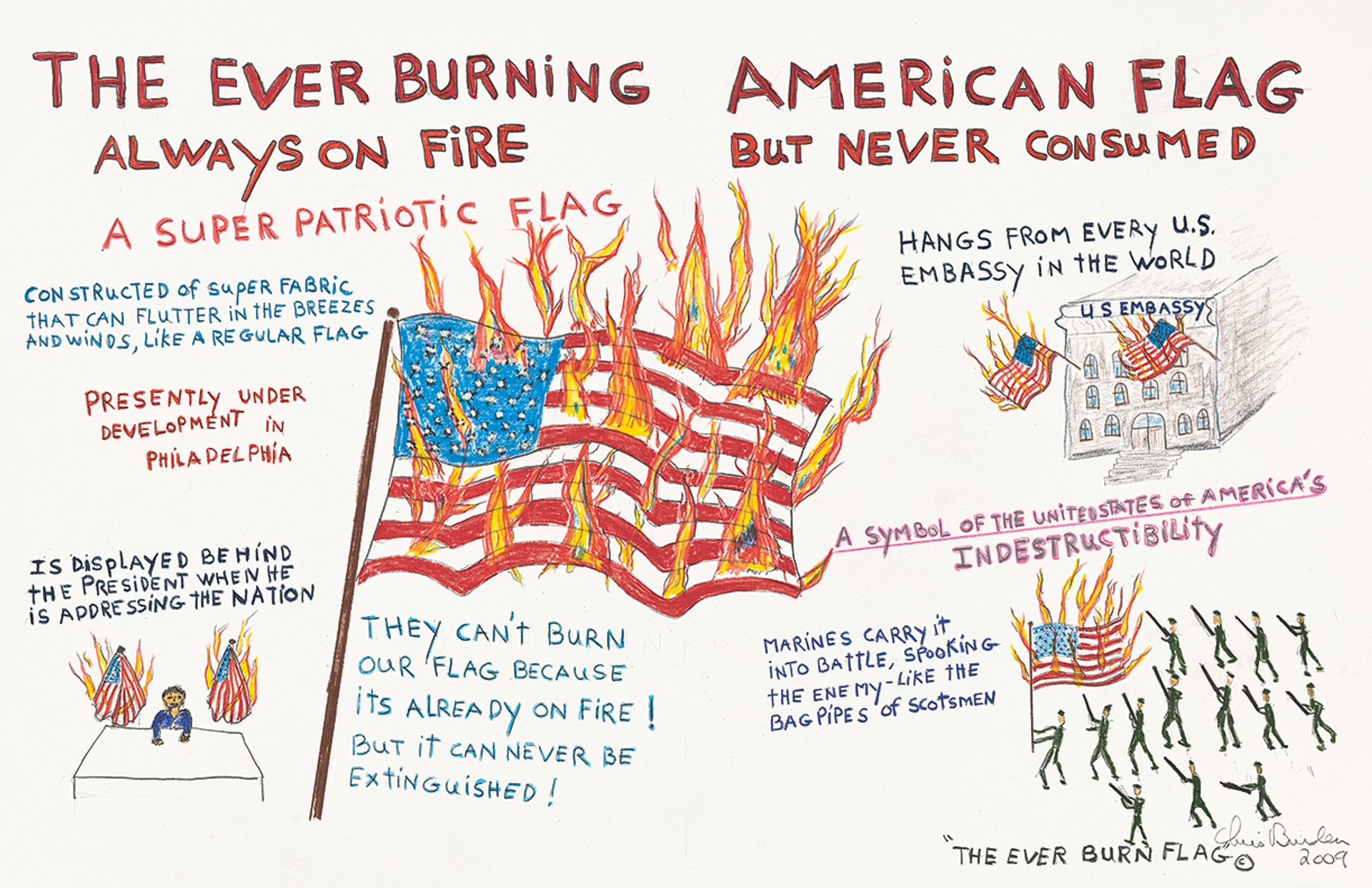

Incendiary idea: Burden’s drawing for The Ever Burning American Flag (2009). He wanted to find a fabric that could stay lit without burning away, but never found the right material Photo: Brian Forrest. All works © 2022 Chris Burden/Licensed by the Chris Burden Estate and Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

On the more surprising side, Burden had the inflammatory idea in 2009 to create an ever-burning American flag out of a material that stays lit without consuming itself, only that material was never identified. He also imagined, starting in the 1980s, several works for the property in Topanga Canyon that he shared with his wife, artist Nancy Rubins, including a single-lane swimming pool that would extend across a canyon like a bridge. He sketched it on a paper plate and kept it on the wall of their tent onsite, where they lived while building their home. One of his goofier notions was the idea of sending a hamster sailing across the Pacific by itself, the animal at the helm, using food conditioning to train it to stay on course.

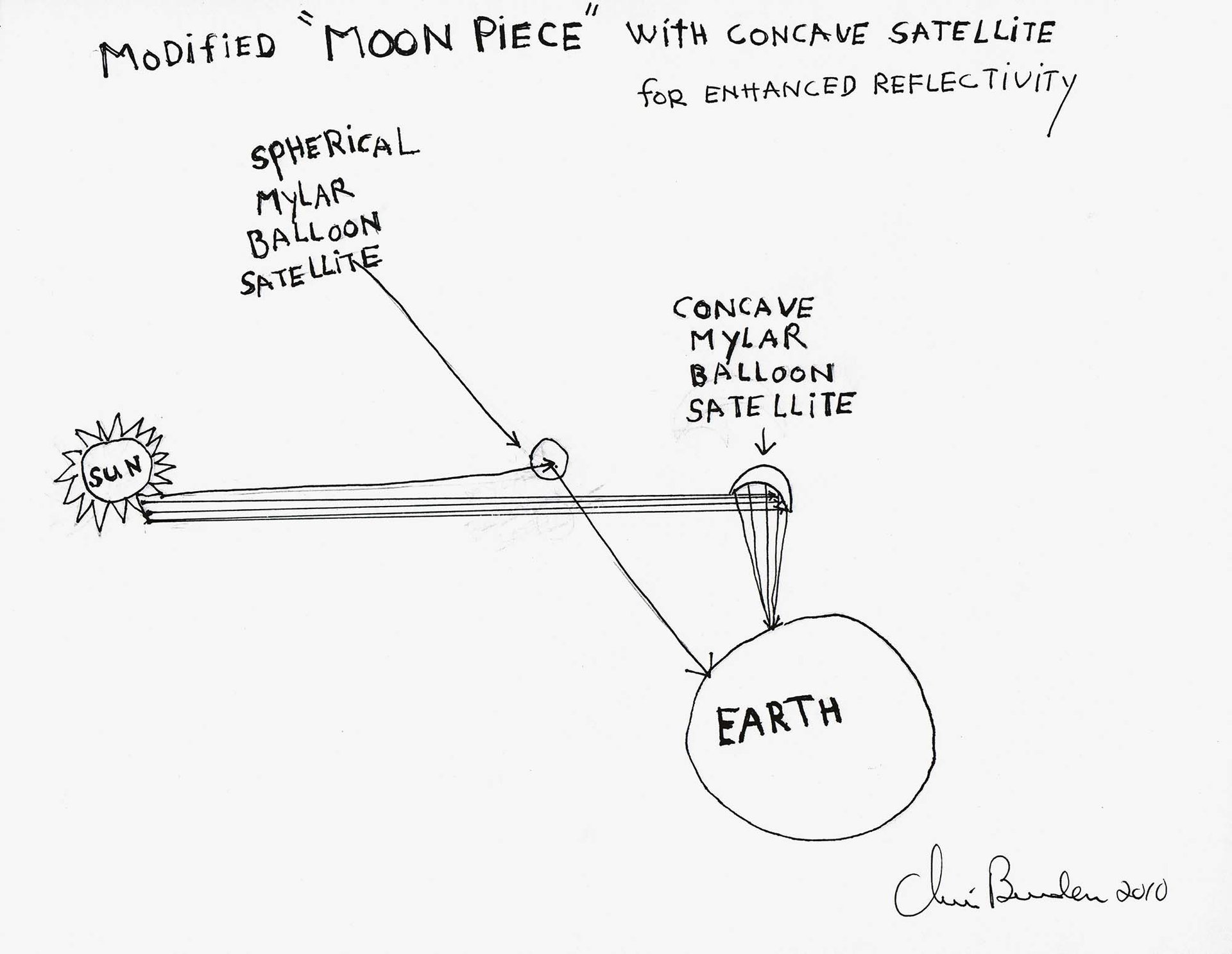

And decades before Trevor Paglen tried to send a mylar balloon into orbit that would be visible to the naked eye, Burden proposed creating a mylar balloon satellite visible from Earth, like “a bright automobile headlamp moving rapidly across the sky”, he wrote in a 1986 letter to Documenta 8 co-curator Edward Fry. He was so taken by the idea, which he called Moon Piece, that when it didn’t work for Documenta, he offered it to the Exploratorium science museum in San Francisco and the arts organisation Creative Time, among others.

Chris Burden, drawing for Moon Piece, 2010 Photo: courtesy the Chris Burden Estate. © 2022 Chris Burden/Licensed by the Chris Burden Estate and Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The satellite wasn’t created for multiple reasons, says Sydney Stutterheim, the art historian who co-edited the new book. “The science had to be there, the technology and also the government,” she says. “They wanted to speak to Nasa to get this made, which was maybe outside the scope of possibility. I wonder myself whether he knew it probably wouldn’t be realised.” (Paglen managed to send his Orbital Reflector satellite up on a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket in 2018, but the balloon did not deploy.)

The limits of physics

Expenses, engineering and technological challenges are some of the leading reasons these works were not made. Not only did Burden test his physical limits with early performances, like crucifying himself on the hood of a Volkswagen Beetle, but his mechanical works often pushed the limits of physics. This is true in finished projects such as Metropolis II at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (Lacma), where the miniature cars move at such high speeds that Burden had to figure out how to keep them from flying off the tracks. It’s also true in many unrealised projects, showing that for all his building skills Burden was not a mechanical engineer in artist’s clothes. He led with his vision, even if it couldn’t easily, safely or, given the state of technology, yet be made.

The artist with Metropolis II (2010)in progress in his studio. The kinetic scultpure is on show at Lacma Photo: Joshua White. All works © 2022 Chris Burden/Licensed by the Chris Burden Estate and Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

As Stutterheim says, “In some ways his unrealised projects are the purest expressions of his imagination, because they were unconstrained by practical considerations. There is something beautiful and informative about them—a direct route to the artist’s thinking.”

Gagosian and Shionoiri said there are currently no plans to produce any of the works in the book. But they are working together to complete another piece, When Robots Rule: The Two-Minute Airplane Factory, which did not function when it was built for the Tate in 1999. Burden’s goal was to create a large machine that could quickly assemble small balsawood, rubber-band-powered airplanes, and ideally launch the planes into the air when complete. Shionoiri says it was particularly challenging to make at the time without access to open-source coding to program the machinery.

Gagosian says there isn’t an exact timeline for the remake, but it might be completed by the end of the year. “We’re hoping it will be realised soon and we want to display it in Los Angeles at the Marciano building,” he says.