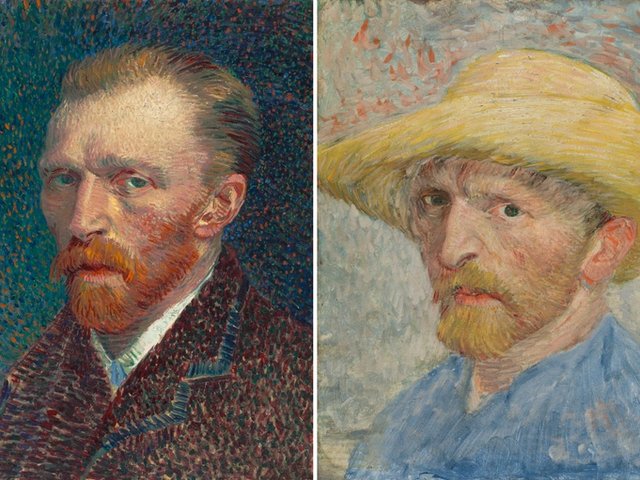

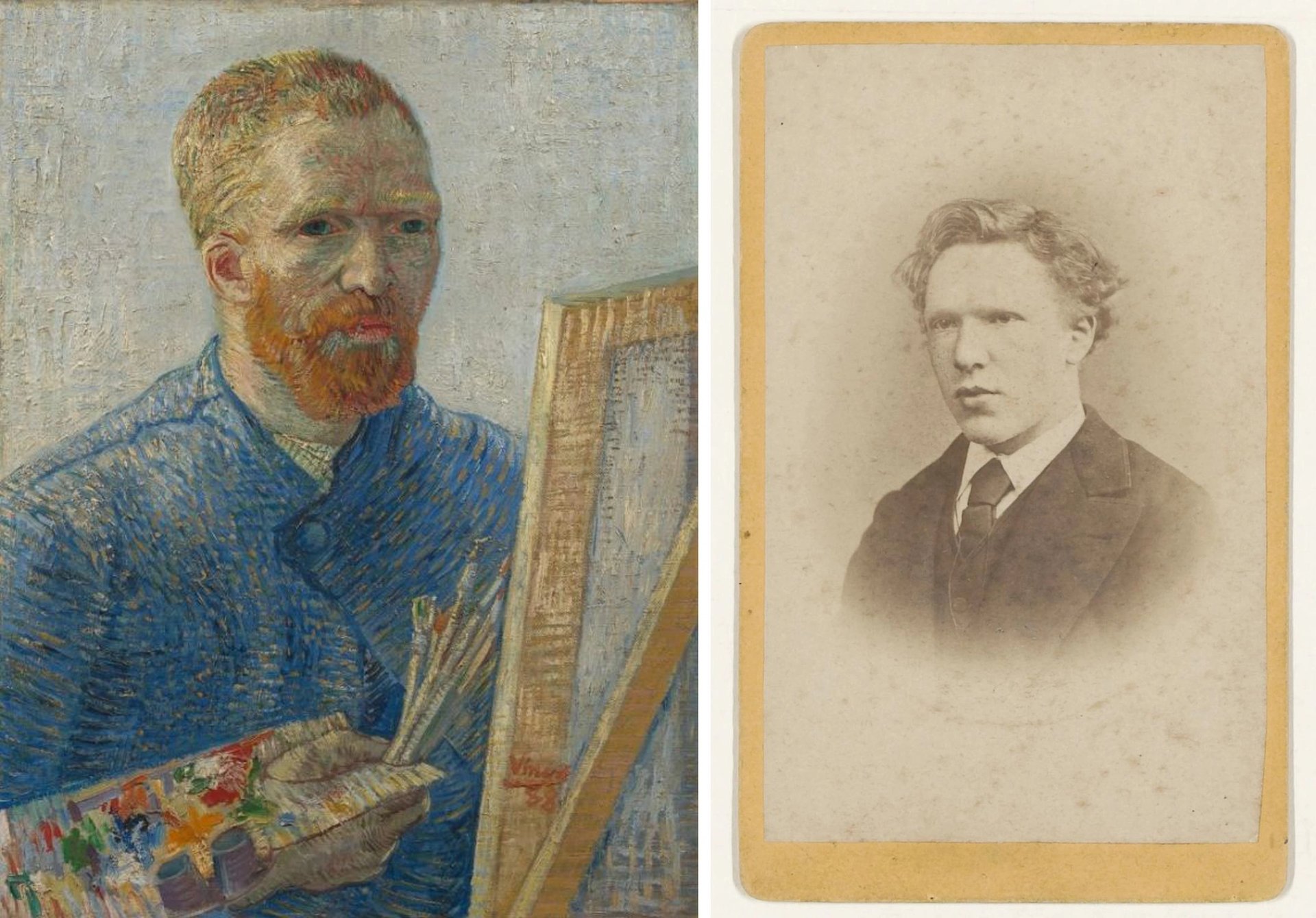

Only a single portrait photograph of Vincent van Gogh survives, from when he was aged 19. So when we imagine his appearance, we immediately think of his self-portraits. Many of these can now be seen at London’s Courtauld Gallery, which is holding the first-ever exhibition of self-portraits from Vincent’s entire career (until 8 May).

Van Gogh’s Self-portrait as a Painter (February 1888) and Photograph of Vincent van Gogh, aged 19 (1873) Credit: Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

But did Van Gogh really look like his self-portraits? Although they date from only a four-year period, 1886-89, it is surprising quite how much his appearance varies in them. Many viewers today, if shown one of the lesser-known self-portraits without a label or context, would be hard-pressed to recognise the face.

Vincent was less concerned about depicting his precise facial features and far more interested in capturing a mood or stylistic effect. He once wrote to his sister Wil that “to my mind the same person supplies material for very diverse portraits”.

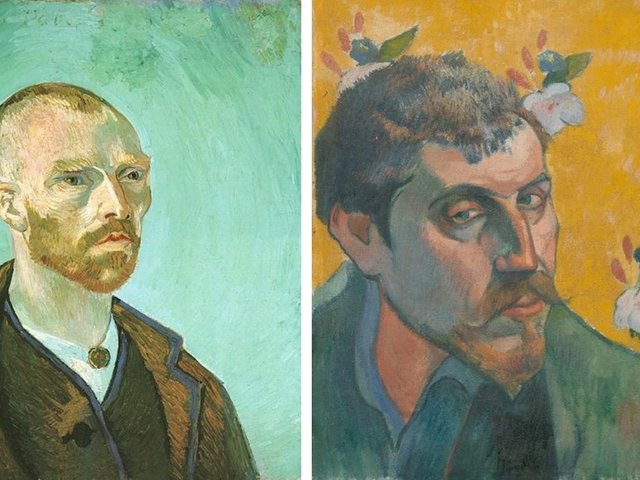

In the absence of photographs, and to get a better idea of Van Gogh’s actual appearance, the self-portraits can be supplemented with depictions of him by other artists.

Many of these portraits of Van Gogh by his artist friends are not well known and they have never been properly considered together as a group. I have reproduced them all for the first time together here and in the Courtauld exhibition catalogue edited by the curator Karen Serres.

What do these portraits tell us about Van Gogh’s appearance? They emphasise his drooping moustache, possibly grown partly to disguise his sunken cheeks and gaunt expression. His beard varies in length in the portraits, from short to medium, and when the portraits are in colour it is usually shown as ginger. Vincent has deep-set eyes, emphasised by his prominent eyebrows. In most of the portraits he looks older than his years (he was then aged between 32 and 37).

But what is more interesting than physiognomy is what the works reveal about his character. Taken as a group, the portraits of Van Gogh show him with a morose and stern expression. There are few signs of a smile, although we should remember that wide grins for photographic portraits are a relatively recent phenomenon.

Vincent usually appears ill at ease in the portraits, perhaps self-contained. This may reflect the fact that society tended to treat him as an outsider, which made him defensive. But arguably the fact that he forged his own path through life made it easier to bravely defy artistic conventions and develop his own unique style.

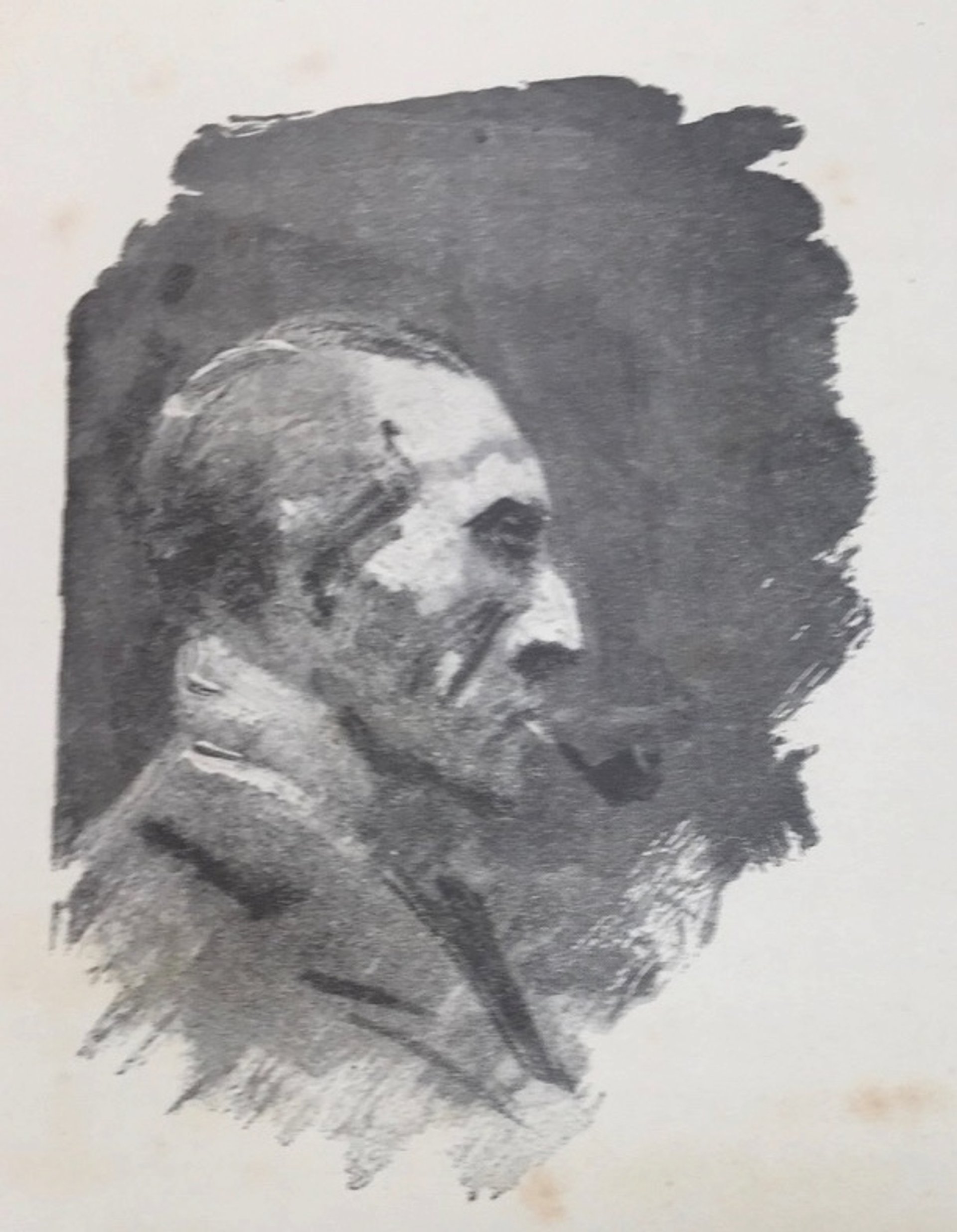

Horace Mann Livens (1862-1936), Portrait of Van Gogh (January-February 1886) Credit: Published in Van Nu en Straks, 1893

Horace Livens, a young London artist, made the earliest portrait of Van Gogh. He was studying in Antwerp when Vincent joined the course for a few weeks. Livens painted a watercolour portrait of his new friend, but it was lost in the early 20th century. All that remains is a small black-and-white image that was reproduced in a Flemish cultural journal. Shown in profile, Van Gogh smokes his beloved pipe, with a determined expression.

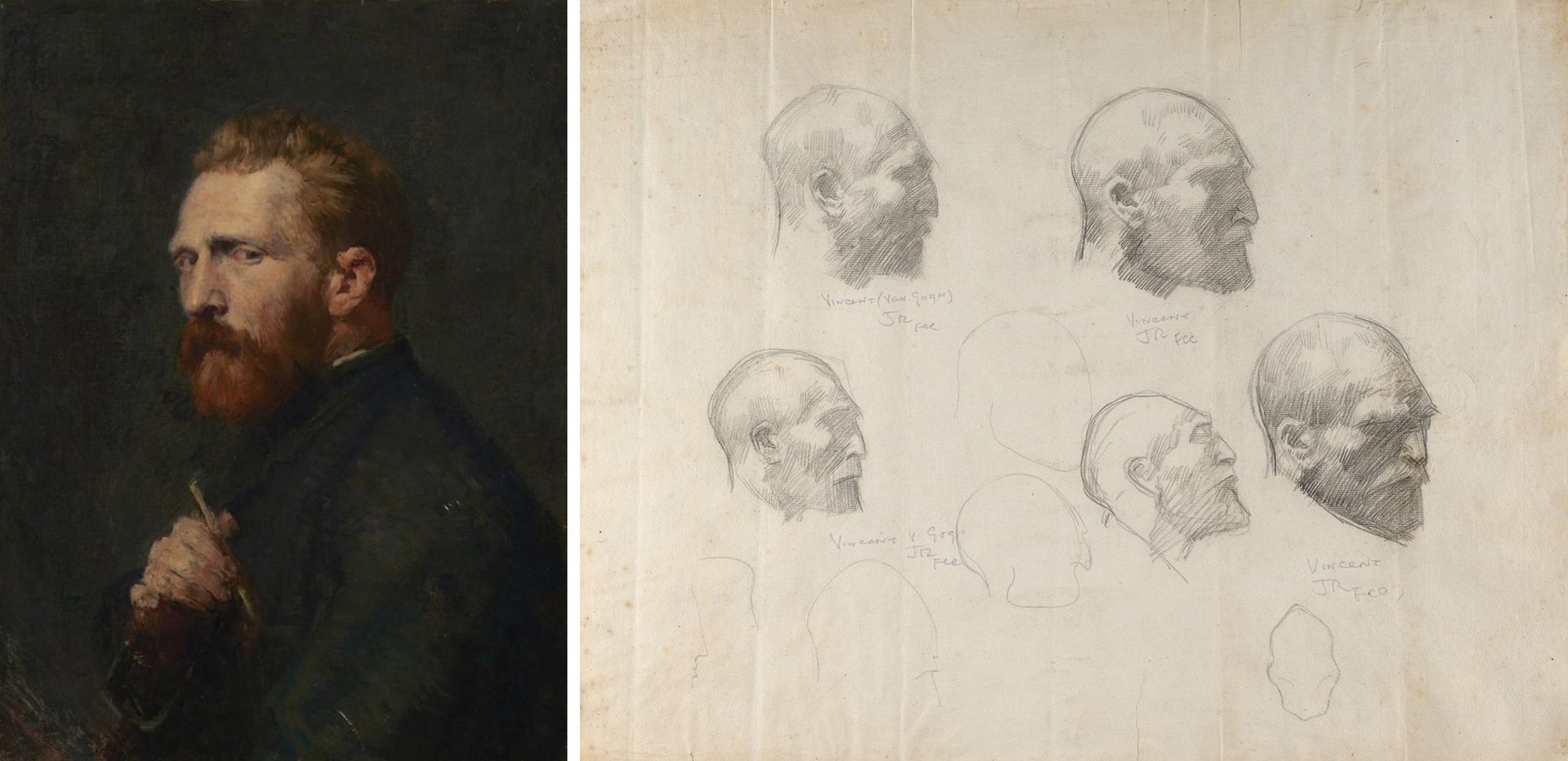

John Peter Russell (1858-1930), Portrait of Van Gogh (1886) and Five Sketches of Van Gogh (1886, possibly 1887) Credit: Painting: Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation) Drawing: Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney (Bridgeman image)

John Russell was an Australian artist who studied with Vincent at Cormon’s studio in Paris in 1886. He made a powerful oil portrait of Van Gogh, traditional in its style. Van Gogh appears smartly dressed, presumably wanting to present himself as a successful artist. He peers back over his shoulder, with a worried expression. Vincent was delighted with the picture, telling Theo to “take good care of my portrait by Russell, which means a lot to me”.

Russell's oil painting is fairly well known, but what may come as a surprise is a large sheet with five sketches which emerged in 2003 from one of his descendants—and was bought by the Art Gallery of New South Wales in Australia. Vincent’s face appears hollow-cheeked, his expression intense.

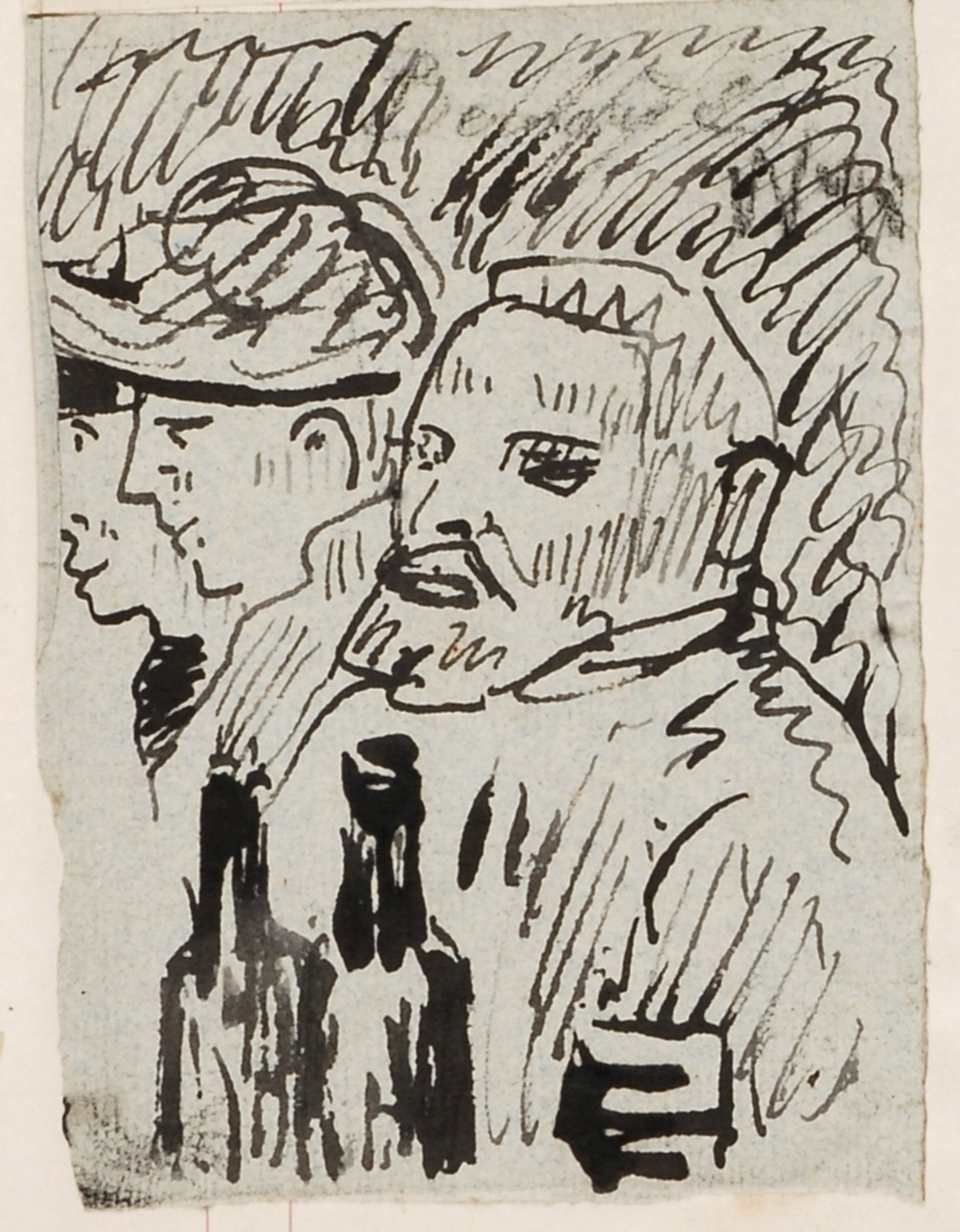

Emile Bernard (1868-1941), Van Gogh (1886-87) Credit: Kunsthalle Bremen

Van Gogh’s closest friend in Paris was Emile Bernard, aged just 17 when they met. This is another relatively unknown sketch, which was discovered in 2015 in an album of his drawings at the Kunsthalle Bremen. Although the identification of the figure as Van Gogh in the bar scene is not absolutely certain, it is very likely. Two bottles lie prominently in front of him, while beside him is a woman, probably a prostitute, and another figure. Vincent appears uninterested in either the drink or his companions, gazing out and seemingly ill at ease.

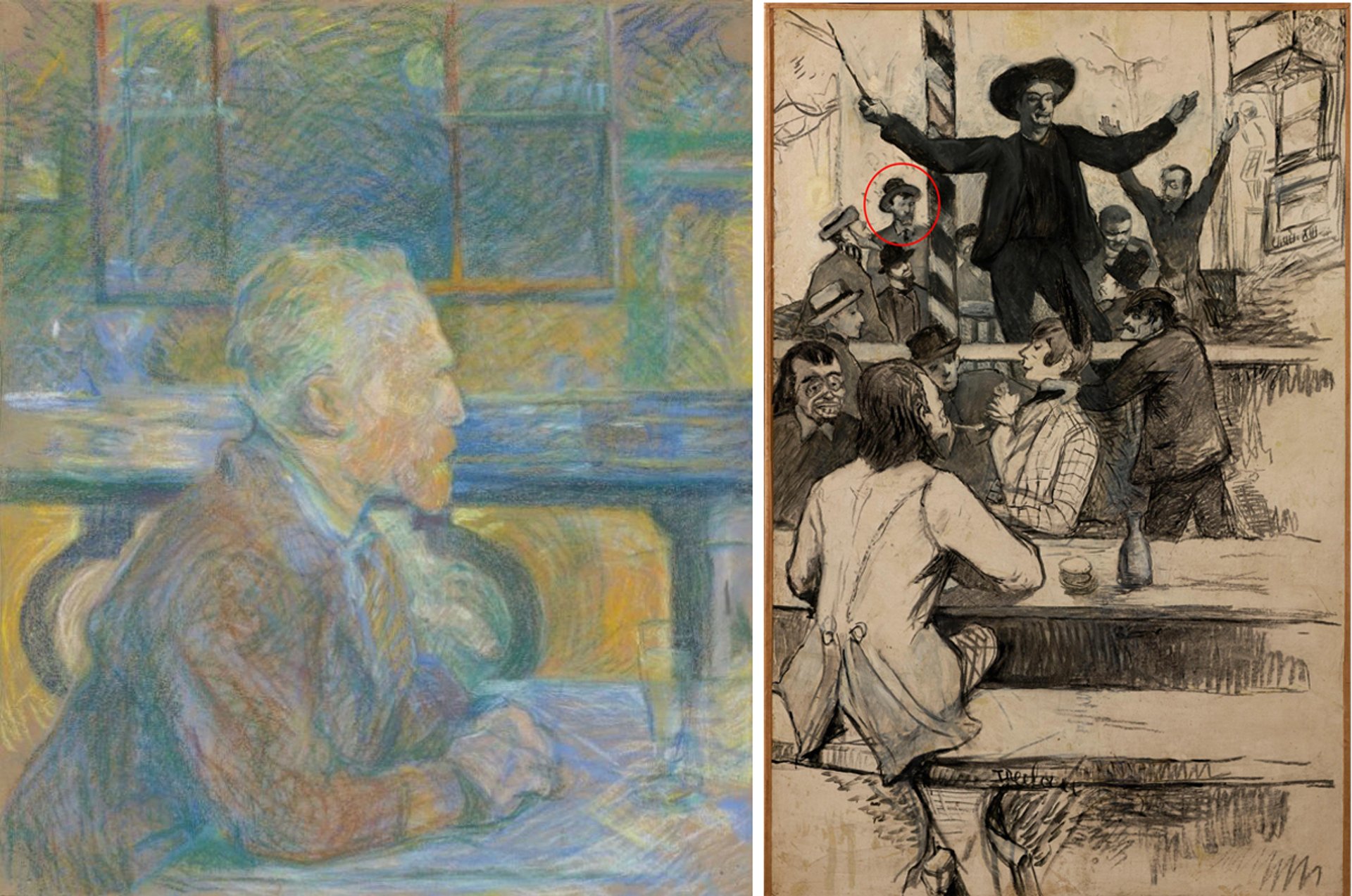

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864-1901), Portrait of Van Gogh (1887) and The Refrain of the Louis XIII-style Chair at the Cabaret of Aristide Bruant (1886), with Van Gogh circled in red Credits: Painting: Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation) Drawing: Hiroshima Museum of Art

The finest depiction of Van Gogh, in terms of what it reveals of his character, is a pastel by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. Once again he is in a bar, with a glass of absinthe. Depicted in profile, he stares intently ahead, apparently deep in thought.

In a second work, a sketch, Van Gogh has been identified by Louis van Tilborgh in this little-known caricature by Toulouse-Lautrec, now at the Hiroshima Museum of Art. The sketch depicts a scene at Le Mirliton, a cabaret run by the popular singer Aristide Bruant. Vincent is almost certainly the small face at the very back, just to the left of the pillar. Once again he is smartly attired, with a tie and hat.

Lucien Pissarro (1863-1944), Vincent and Theo van Gogh in Conversation (1887) Credit: Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

I have identified this drawing by Lucien Pissarro as the only depiction of Vincent and Theo together. Deep in conversation, Theo is on the right, with Vincent on the left. Theo is dressed more formally with a top hat, whereas Vincent wears the soft felt hat which appears in some of his self-portraits.

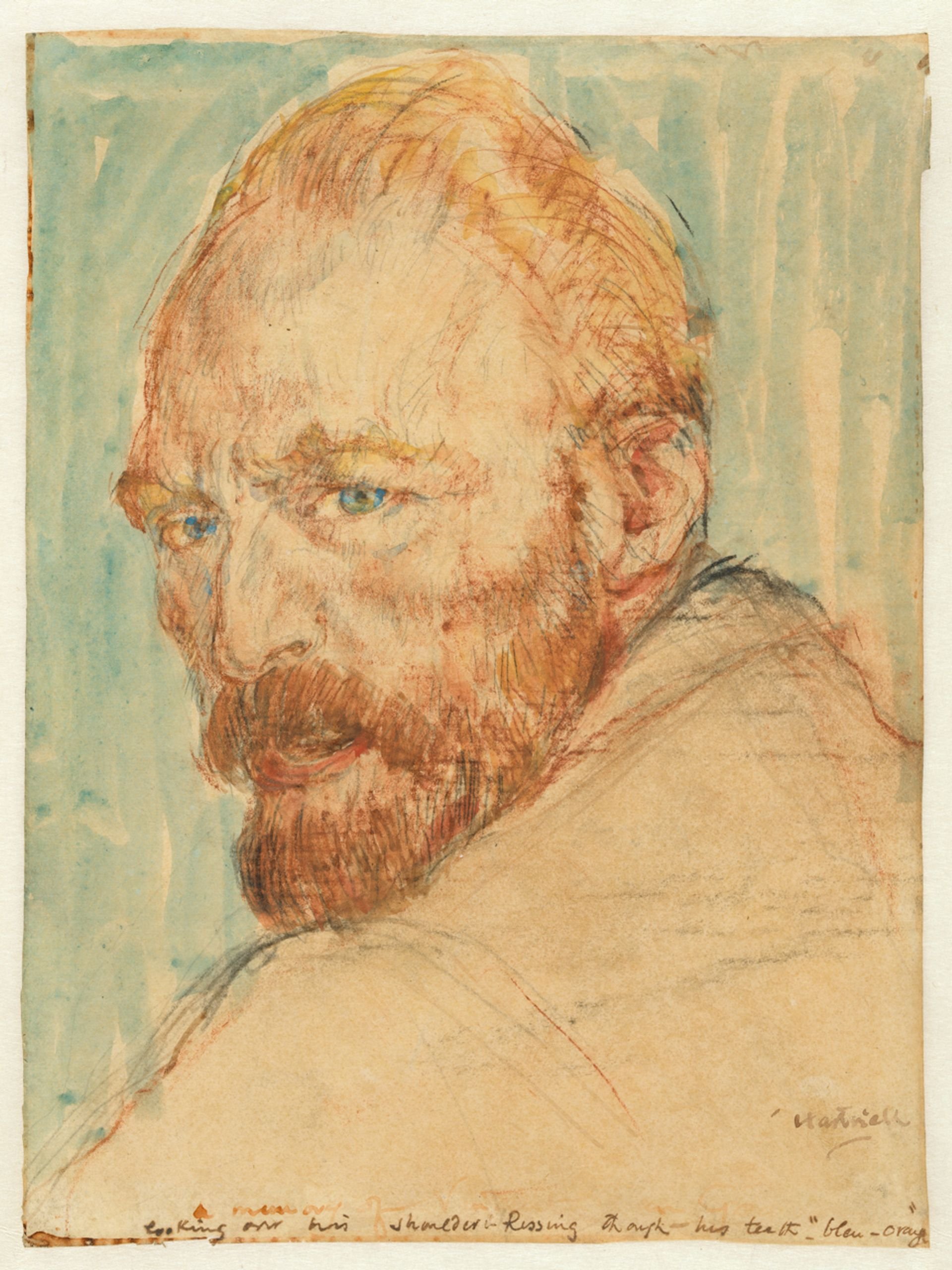

Archibald Standish Hartrick (1864-1950), Portrait of Van Gogh (1913) Credit: Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

Archibald Hartrick left London in 1886 to study art in Paris, where he met Van Gogh. This watercolour was done some years later. Although long assumed to date from the late 1930s, I have found documentary evidence to date it to 1913, making it closer to the time that they were together. Hartrick emphasises Van Gogh’s ginger hair, trimmed beard, floppy moustache and receding hairline. His eyes are blue, with his mouth partly open as if to speak.

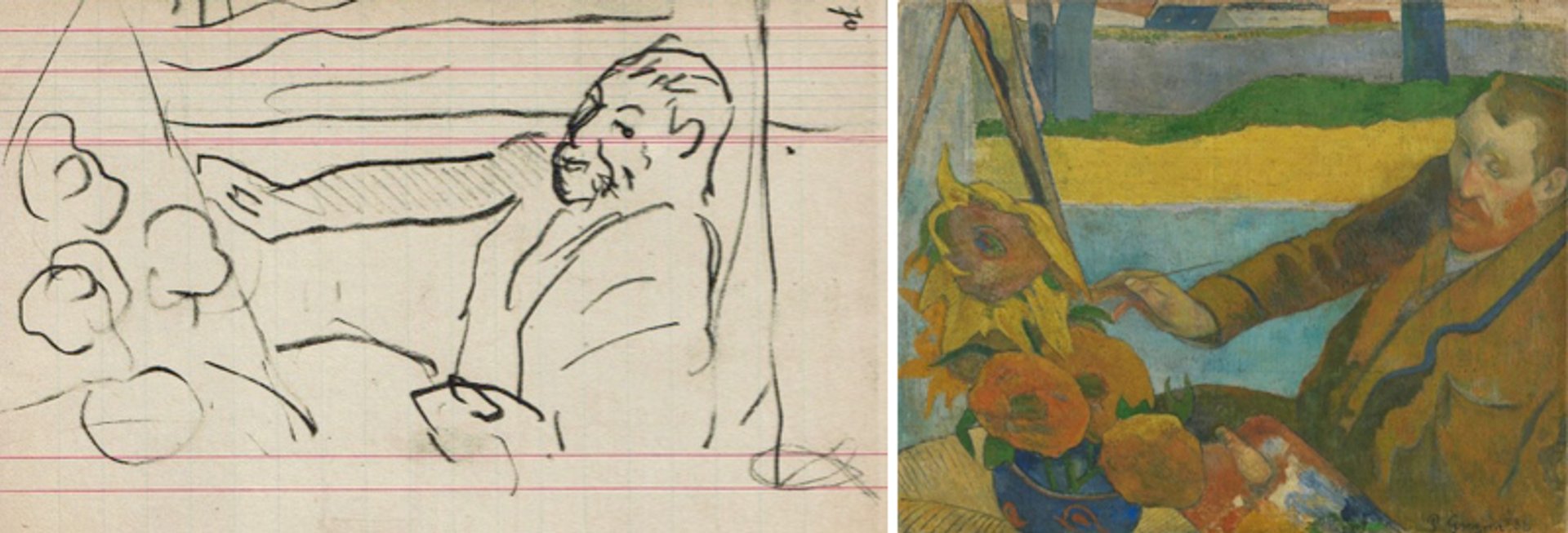

Paul Gauguin (1848-1903), Sketch for Vincent van Gogh Painting Sunflowers (December 1888) and Vincent van Gogh Painting Sunflowers (December 1888) Credit: Drawing: René Huyghe, Le Carnet de Paul Gauguin, 1952 (Israel Museum, Jerusalem) Painting: Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

Paul Gauguin’s Vincent van Gogh Painting Sunflowers dates from early December 1888, just a few weeks before Van Gogh mutilated his ear and his companion fled back to Paris. Nearly a year later Vincent referred to the picture in a letter to Theo: “My face has lit up after all a lot since, but it was indeed me, extremely tired and charged with electricity as I was then.” According to Gauguin, Van Gogh had told him at the time: “It’s me all right, but me gone mad”. Gauguin’s rough drawing for the composition survives in a sketchbook.

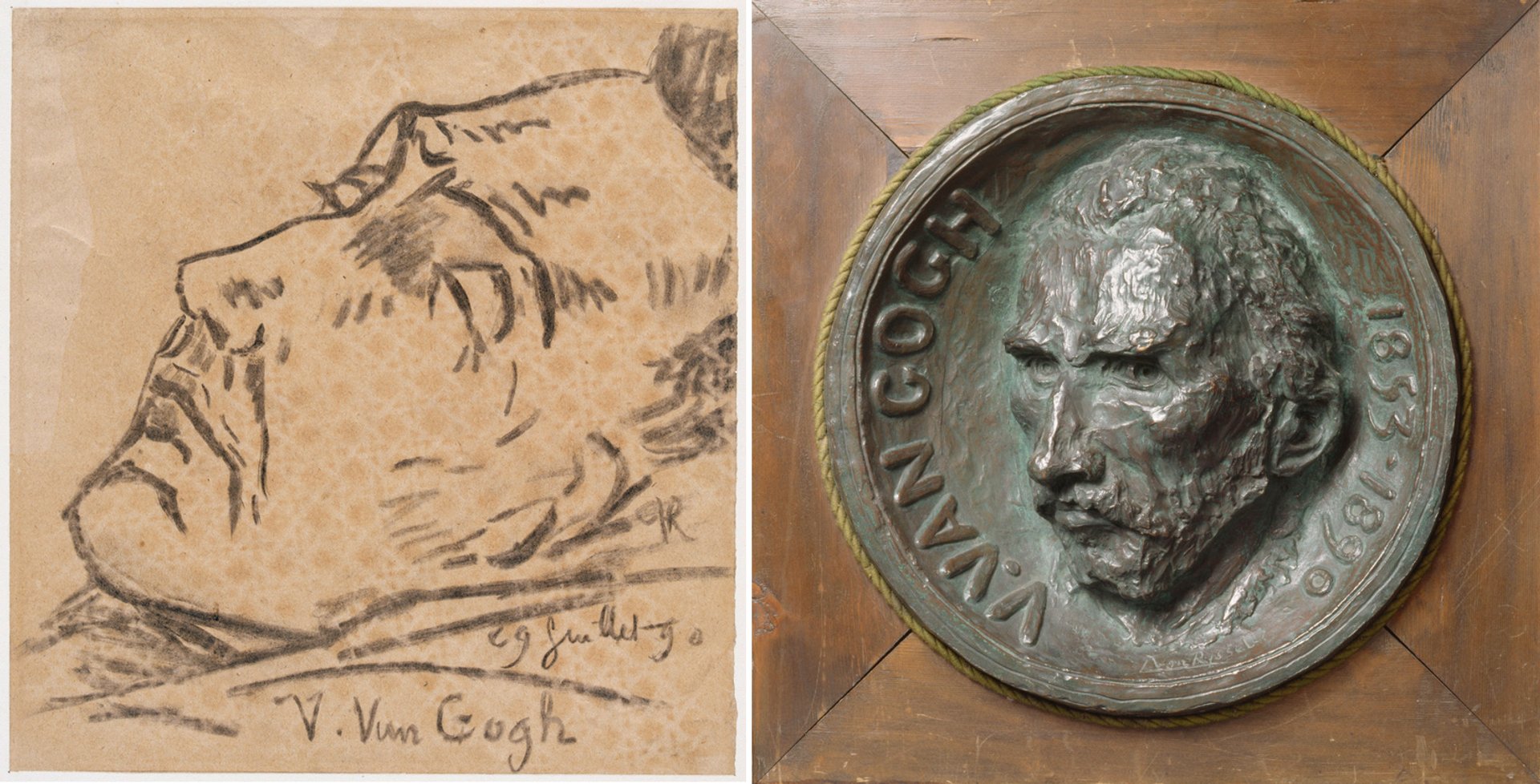

Dr Paul Gachet (pseudonym Paul van Ryssel) (1828-1909), Van Gogh on his Deathbed (July 1890) and Paul Gachet Jr (pseudonym Louis van Ryssel) (1873-1962), bronze medallion for Van Gogh’s grave (1905) Credit: Musée d’Orsay, Paris (Photo RMN - Franck Raux and Hervé Lewandowski)

This portrait is completely different—a deathbed drawing. It was made by Dr Paul Gachet, who treated Van Gogh after he had shot himself in Auvers-sur-Oise on 27 July 1890, leading to his death two days later. The doctor, an amateur artist, sat beside his bed and sketched his friend. Dr Gachet made no attempt to idealise Vincent’s lifeless features, depicting the mouth downturned and the eyes closed.

In 1905 Vincent’s body had to be moved to a new grave, an event that has had surprisingly little coverage in the Van Gogh literature. At this point the doctor’s son, Paul Gachet Jr, designed a medallion to be affixed to the headstone. Although the bronze was cast, it was never attached. Vincent’s sister-in-law Jo Bonger felt that the grave should be kept simple—reflecting the artist’s personality.