Unlike in 2009, when Copenhagen was over-optimistically rebranded Hopenhagen for the United Nations Climate Change Conference, participants at Cop26 in Glasgow (until 12 November) are far more realistic.

The Danish-Icelandic artist Olafur Eliasson, who is presenting a number of works in Glasgow in the coming weeks, says care should be taken over “normalising the use of the word hope”. He thinks the numbers no longer add up. “I’m gradually recognising that, I’m afraid,” he says. “And I have normally been confident when looking ahead. Personally, I don’t think [politicians] can achieve a solution to the climate crisis. But I hope [they] come up with a viable route to delay the disastrous consequences of it.”

The South African social and environmental justice activist Kumi Naidoo, who is presenting a film with Eliasson at Cop26 on how the worlds of art and activism can together achieve commonly held climate goals, is equally wary. As he puts it: “We are living in the most consequential decade in humanity’s history. What we do in the next ten years will determine what kind of future we have—and whether we have a future at all. We still have a window of opportunity, but, if we are brutally honest, that window of opportunity is small, and it is fast closing.”

Just a few months ago, the UN's Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change warned that global warming has become a "code red for humanity".

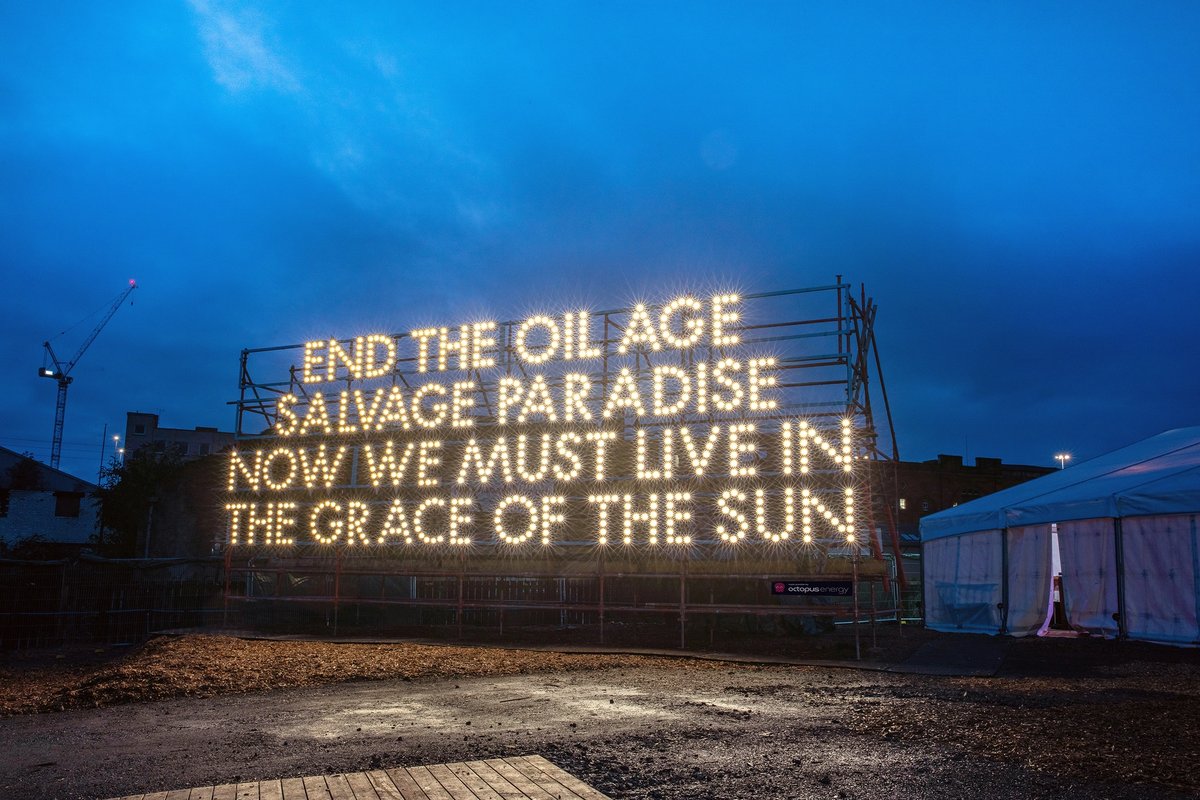

Alongside the film, Eliasson has collaborated with the Scottish artist and poet Robert Montgomery, whose light installation, on show at the Landing Hub—a fringe festival of Cop26—implores us to “salvage paradise” and is powered by 1,000 Little Sun solar lamps. Eliasson has been developing his Little Sun project for the past ten years, delivering 1.5 million solar lamps to people living without electricity in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Olafur Eliasson and Minik Rosing's Ice Watch (2014) at Place du Panthéon, Paris, in 2015. Photo: Martin Argyroglo. Courtesy of the artist; neugerriemschneider, Berlin; Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York / Los Angeles © 2014 Olafur Eliasson

It is not the first time Eliasson has participated in the global climate summit. In Paris in 2015, he presented Ice Watch, for which the artist brought 30 ice chunks from Greenland to the Place du Panthéon where they slowly melted for the duration of the summit. The work was subsequently installed at two London sites in 2018—one outside the Tate Modern in Bankside and the other in the City of London outside Bloomberg’s European HQ. Eliasson, who has been moving towards operating a sustainable studio for several years, openly published the carbon footprint of the London leg of the project, whose CO2 emissions totalled 55 tonnes, according to the charity Julie’s Bicycle.

The key now, both Eliasson and Naidoo believe, is solidarity and an ability to build dialogues across different perspectives. “The challenge for all of us is, can we actually develop the capability to genuinely express love and understanding for the people who voted for Brexit, for Trump and for Bolsonaro?” Naidoo says. “Activists and progressives can learn from the Steve Bannons and the Karl Roves of the world—they understand much better that culture drives politics and society, not the other way around.”

Naidoo, who became an anti-apartheid activist when he was just 15, also notes how art can become an empowering tool for people. “During the liberation struggle in South Africa, we had large numbers of people not able to read and write, so the way that we created a possibility for those people to have agency was through a sensitive use of arts, culture, music, song and dance,” he says. “What I learned as a very young activist was, unless you connect the different energies—your trade unions, women’s groups, intellectuals, artists, theatre groups and so on—you don’t have the capability to shift things as fast as we need to.”

The need for intersectionality is a crucial piece of the puzzle, Eliasson points out. “I’m a part of the privileged Global North, where we need to thoroughly reassess the ideas and values that created wealth through extraction and violence on which we base our welfare societies today,” he says.

As for the future—if indeed there is one—Eliasson and Naidoo are looking to the next generation. In 2020, Eliasson launched Earth Speakr, a work of art comprising an app, a website and physical presentations that invite children from across Europe and beyond to speak up for the future of our planet. Eliasson says: “Children don’t lie, which makes them very unlike the rest of the society. They’re not born racist, homophobic or misogynistic, it’s passed onto to them. Here we have a good, solid base to build on.”

Naidoo agrees. “What is needed right now is a fresh lens through which to look at old problems—problems that our generation was just not able to address with the intensity and urgency that it needed,” he says. “Celebrating the participation of young people is also about helping us to imagine future realities that we didn’t.”