In Venice, the mean water level has reached a height that is unprecedented in the history of the city. Since 1897 (when zero datum was established at the tide gauge station of the Punta della Salute), the water level in the lagoon has increased by at least 35cm.

If no adequate measures are taken, the future and unavoidable rise in sea levels, confirmed by numerous studies, will not only make living in the city almost impossible, but will lead to ever more dramatic and frequent destruction of its buildings, threatening the city’s very existence.

There is no doubt that rising damp by capillary action, caused by the progressive rise in the water level, is the main reason why the entire fabric of the city (around 15,000 buildings) is degrading. The brackish water impregnating the subsoil in which the foundations are immersed now rises up the supporting walls of the buildings to a height of several metres.

It is a continuous phenomenon: the water evaporates, leading to ever greater and abnormal concentrations of salt (in a cubic metre of wall it is not uncommon to find 70kg-80kg of salt) that dissolve and recrystallise again and again in a continuous cycle, attacking the lower walls.

Gradually, but with exponential progress, the acque alte wash against the bases of the buildings; the brackish water rises higher and higher and the architectural heritage decays day by day.

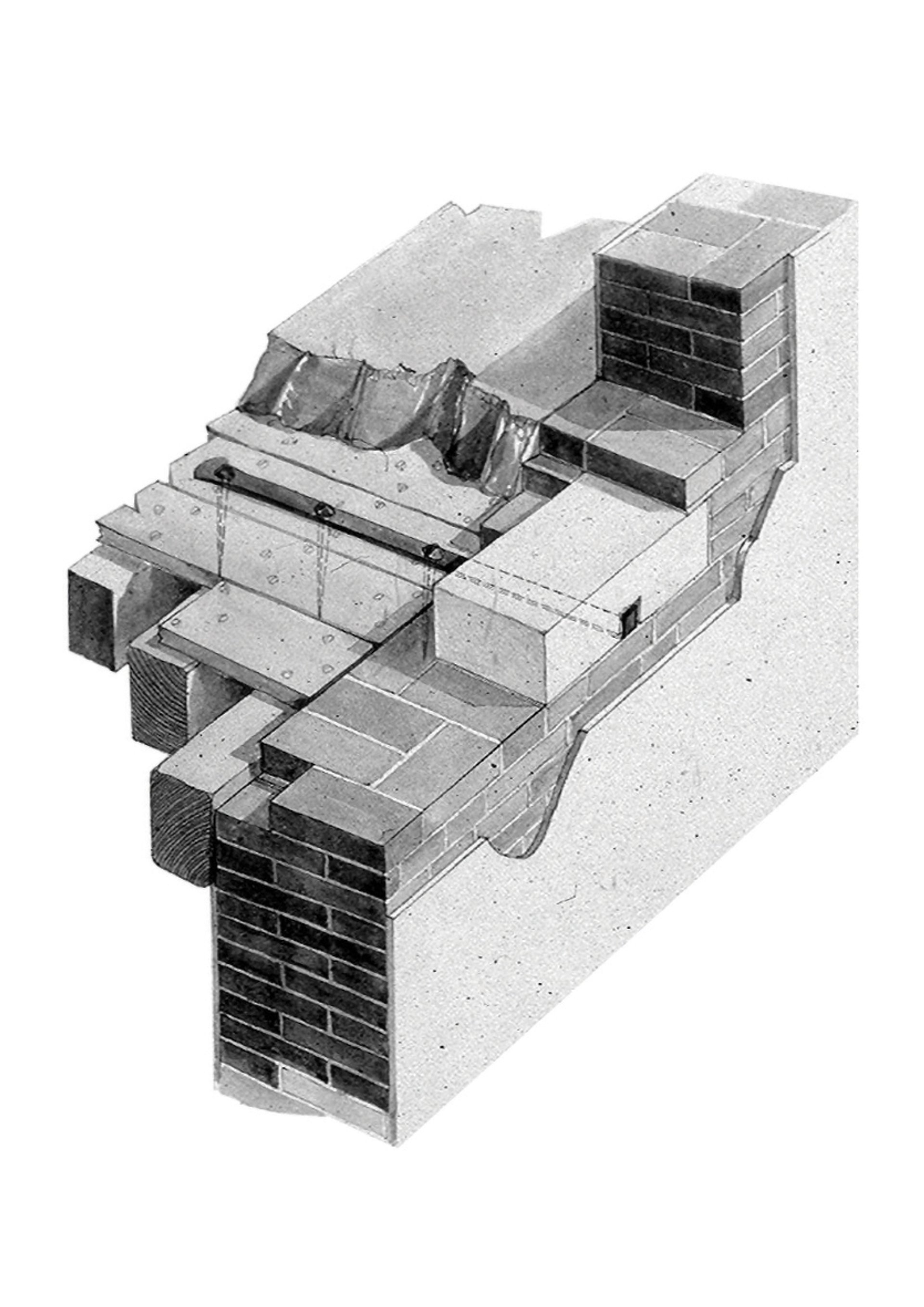

Diagram of the role of the iron tie rods in connecting the floor to the exterior wall of the building. Due to the rising damp, many of these steel elements, which are essential to the stability of Venetian buildings, are rusting through.

© Mario Piana

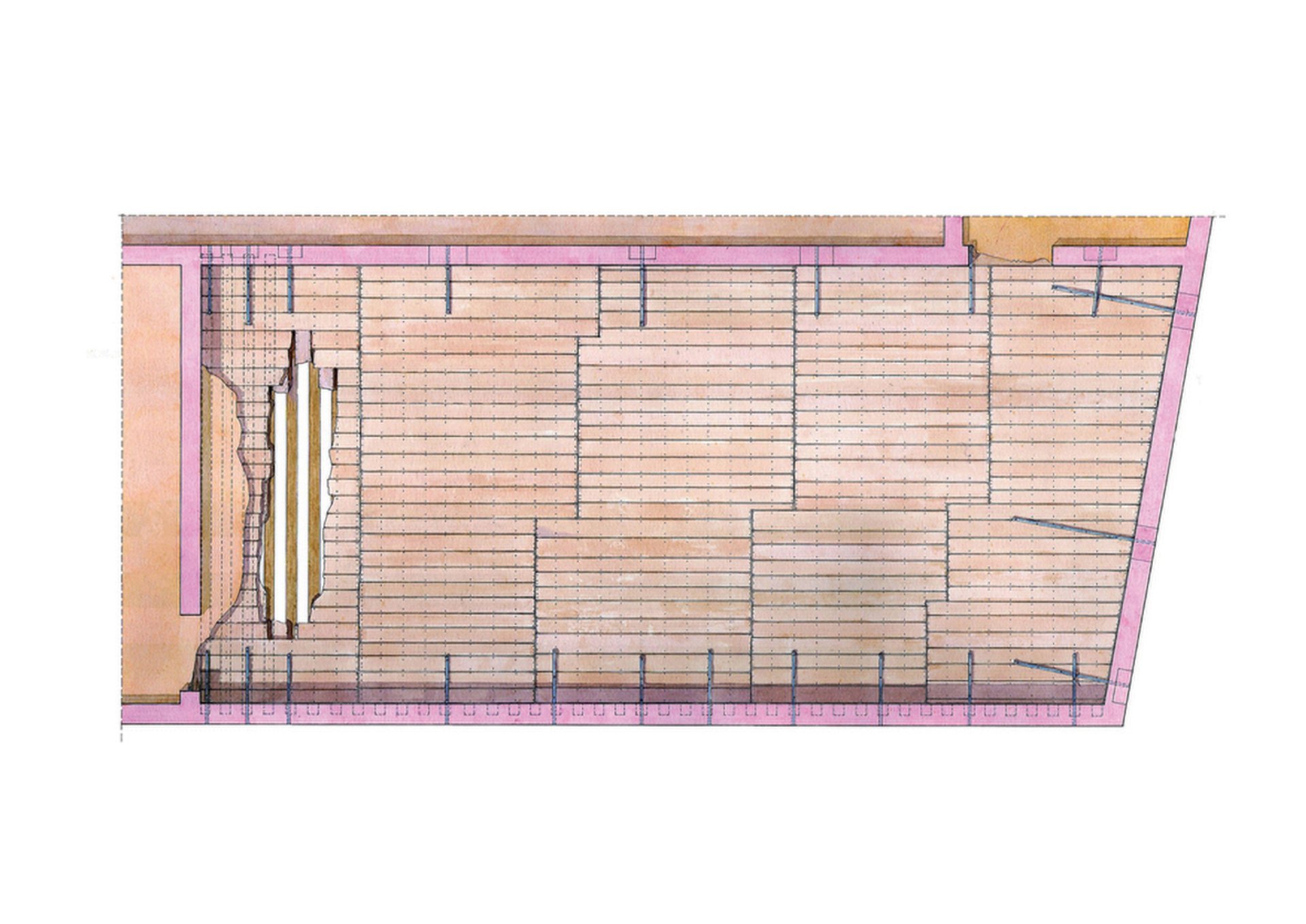

The bricks, stone, mortar and plaster are disintegrating up to the level of the first floors and even higher. This assault on the fabric of the city is now so pronounced as to trigger ever more dangerous structural failures. These continuous cycles of dissolution and saline recrystallisation are gradually affecting the brick walls of the buildings, which are all particularly thin. The reduction of even a few centimetres in their thickness, combined with the sometimes-complete rusting through of the iron tie rods that connect the walls with the wooden floors, which have an essential stabilising role in the construction of the buildings, is generating ever more frequent cases of elastic instability that manifest themselves in gross deformations of the walls, the most severe—and dangerous—stress to which masonry can be subjected.

Rendering of a Venetian floor showing numerous tie rods connecting it to the walls. © Mario Piana

The damage caused by the capillary rising damp can be contained, even if not eliminated, by creating damp-proof courses in the walls, which have to be accompanied by removing the lower courses of the brickwork, brick by brick, and replacing them with new ones; or by a process of desalinisation through lengthy washing techniques, which better respects the historic fabric of the building.

These are, however, demanding and expensive measures, whose benefits will be much reduced by a rise in the water level of just 20cm-30cm (what the IPCC 2021 report foresees if global warming is limited to two degrees), and completely nullified if the rise is 70cm (if there is an increase of three degrees).

• Mario Piana is a professor of architectural conservation at the Università IUAV of Venice, and fellow of the Istituto Veneto delle Scienze, Lettere ed Arti