One of the most memorable scenes in Bitter Lake, Adam Curtis’s damningly prescient 2015 BBC documentary about the UK, America and Russia’s ill-fated interventions in Afghanistan, is when a British art historian tries to explain Marcel Duchamp’s 1917 Fountain to a class of Afghan women. She tells them that Duchamp repurposing a urinal was an expression of political freedom. Her audience looks utterly incredulous. The camera then focuses on the lecturer, who looks as if she cannot believe what she is saying either.

Liberal democracy’s attempts to mould Afghanistan in its own image have ended in humiliating failure, ceding control to the Taliban. This is an era-defining defeat. The New Yorker wonders whether the US withdrawal from Afghanistan marks the “end of the American empire,” adding to general hand-wringing about the wider decline of liberal democracy itself. According to the Economist, just over 8% of the world’s population currently lives in a fully functioning democracy. That number is likely to get smaller. As the Italian Marxist philosopher Antonio Gramsci, who died in a Fascist prison in 1937, put it: “The crisis consists precisely in the fact that the old is dying and the new cannot be born; in this interregnum a great variety of morbid symptoms appear.”

In the current interregnum, there is growing talk of “post-liberal” politics. On the political right, this manifests itself in forces whose authoritarianism can resemble, by subtle, insidious degrees, “lite” versions of what happened in Germany and Italy in the 1930s, even within liberal democracies themselves.

Meanwhile, the left, notwithstanding the Democrats’ victory in the US 2020 elections, is struggling to come up with electable alternatives.

“Today’s fascism no longer needs a Hitler, a Mein Kampf, or a regular corps of stormtroopers,” says the British commentator Paul Mason in a recent opinion piece on inews.co.uk. “Instead it has Facebook, the gaming channels Steam and Discord, the Telegram messaging service and the algorithms that push far-right video content onto the screens of people Google deems likely to enjoy it.”

Spiritless hunk of nonsense

One small uncomfortable fact of this matter is that the liberal beliefs that underpin today’s international art world are only shared by a tiny minority of the global population. Yet the West’s art establishment continues to label as “bad” anything that does not conform to such orthodoxies. Public sculpture remains the prime battleground for art’s culture war. A 19th-century statue of a slave trader can be happily dumped into Bristol harbour, but the West abominates the Taliban’s destruction of ancient stone buddhas.

“This idea of aesthetically-crafted artefacts put inside museums or galleries or private homes is a very special Western phenomenon that’s been exported to the rest of the world, thinking there is a utopia, a global art world,” says Jacob Wamberg, a professor of art at Aarhus University in Denmark. “But it’s still very much defined by Western criteria,” adds Wamberg, the co-editor of the 2010 essay collection, Totalitarian Art and Modernity. The collection challenges notions that totalitarian art is somehow not “true” art and is confined solely to politically suspect regimes.

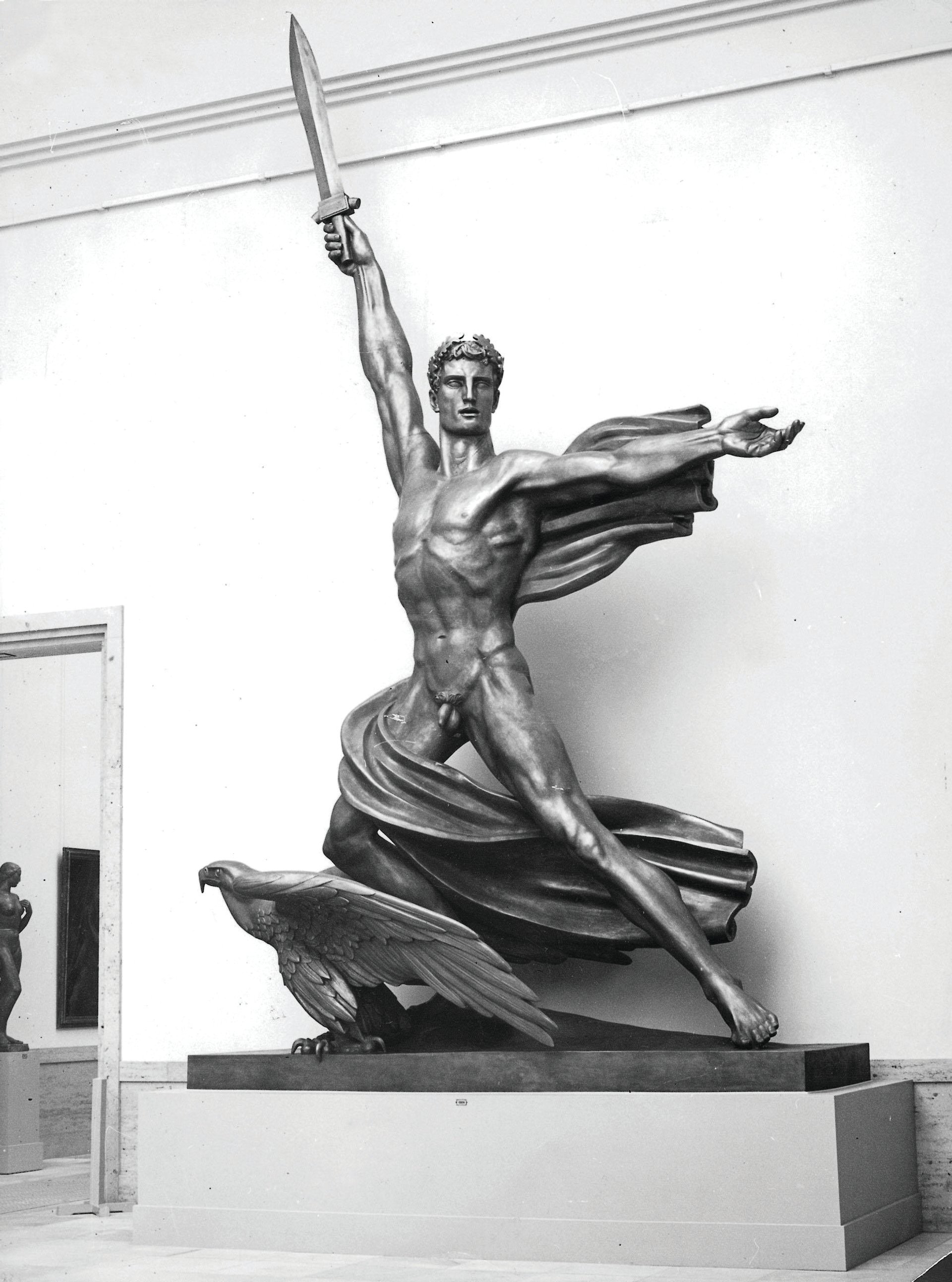

Genius of Victory (1940) by the Nazi sculptor Adolf Wemper. Photo: Süddeutsche Zeitung/Alamy Stock Photo

Ian Rank-Broadley’s populist realist statue of Princess Diana, for instance, which could look equally at home in a shopping mall or one of Hitler’s Great Exhibitions of German Art, was dismissed by the art critic Jonathan Jones in the Guardian as a “spiritless and characterless hunk of nonsense”. Jones had also lambasted Damien Hirst’s sword-wielding statue Verity (2012) in Ilfracombe, Devon as resembling something dreamed up by a deranged dictator, drawing comparisons with the colossal Soviet The Motherland Calls statue commemorating the dead of the Battle of Stalingrad. Verity also has creepy similarities with Genius of Victory, a monumental 1940 sword-

toting bronze by the Nazi sculptor

Adolf Wamper.

Albert Speer, Hitler’s architect, recalled in his diaries that the Führer was “obsessed with gigantism” and there was a “curious sameness” about all his architectural ideas. Totalitarian gigantism certainly characterises the design of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s new parliament building in Delhi, as well as Vladimir Putin’s kitsch-classical palace overlooking the Black Sea, the subject of a courageous documentary by opposition leader Alexei Navalny.

But is there not also a totalitarian sameness to the new hyper-exclusive pencil towers of Manhattan, and the dozens of luxury apartment blocks reconfiguring London’s skyline?

“They’re not totalitarian, unless you regard global capital as totalitarian. They’re not even ugly,” says Stephen Bayley, the former director of London’s Design Museum, of the homogeneous luxury apartment blocks sprouting up across the world. “They’re utterly banal. They’re the built expression of a profit and loss account,” Bayley adds. But wasn’t banality, the normalisation of awfulness, exactly one of the things that, according to Hannah Arendt, characterised Nazi Fascism?

Benjamin Martin, an associate professor in the department of history of science and ideas at Uppsala University in Sweden defines Fascism as a distinctive political ideology deployed by repressive nation states, an F-word that shouldn’t be loosely applied to contemporary cultural trends.

“Back in the 20th-century Fascist moment, capital needed the fascists to take control of the state, not least so as to suppress organised labour,” Martin says. “Google doesn’t need a dictator. Today capital gets what it needs from the political system, and it will get what it needs from the cultural system.”

And that system, at least in terms of contemporary art, is providing the sort of returns capital is looking for despite, or even because of, the pandemic. Damien Hirst’s The Currency project of 10,000 NFTs has so far raised about $20m for the artist and his backer. You might not want to be the owner of an international art fair at the moment, but overall auction sales have returned to pre-Covid levels and prices have soared for works by coveted painters, making massive profits for sellers who bought early from galleries.

The current Mixing It Up: Painting Today exhibition at the Hayward Gallery in London, features paintings by 31 UK-based artists from a range of backgrounds, nationalities and generations, including some current saleroom favourites. It might seem the civilisational antithesis of a 1940s Great Exhibition of German Art or the brazenly right-wing “Political Art” show currently ruffling feathers at the Ujazdowski Castle Center for Contemporary Art in Warsaw. But all are representative of distinct cultural systems and moments.

The introductory text for the Hayward show, curated by the gallery’s director Ralph Rugoff, says the selected paintings are “conceptually adventurous”, undoing our “ingrained ways of seeing and thinking”. Subversion is a traditional trope of the liberal art establishment that stretches back to Duchamp and beyond. The jolt of avant-garde art somehow makes us freer. Yet the whole notion of “freedom”, let alone artistic freedom, has become more problematic in democracies as capital and technology tighten their hold over our daily lives, and culture wars make us more intolerant, whichever trench we happen to be in. These are the forces that now subvert and dictate.

Google “post-liberal art”. At the moment it doesn’t exist. Maybe it’s time for the Eight Percent to open their minds to this kind of creative jolt, whatever it turns out to be.