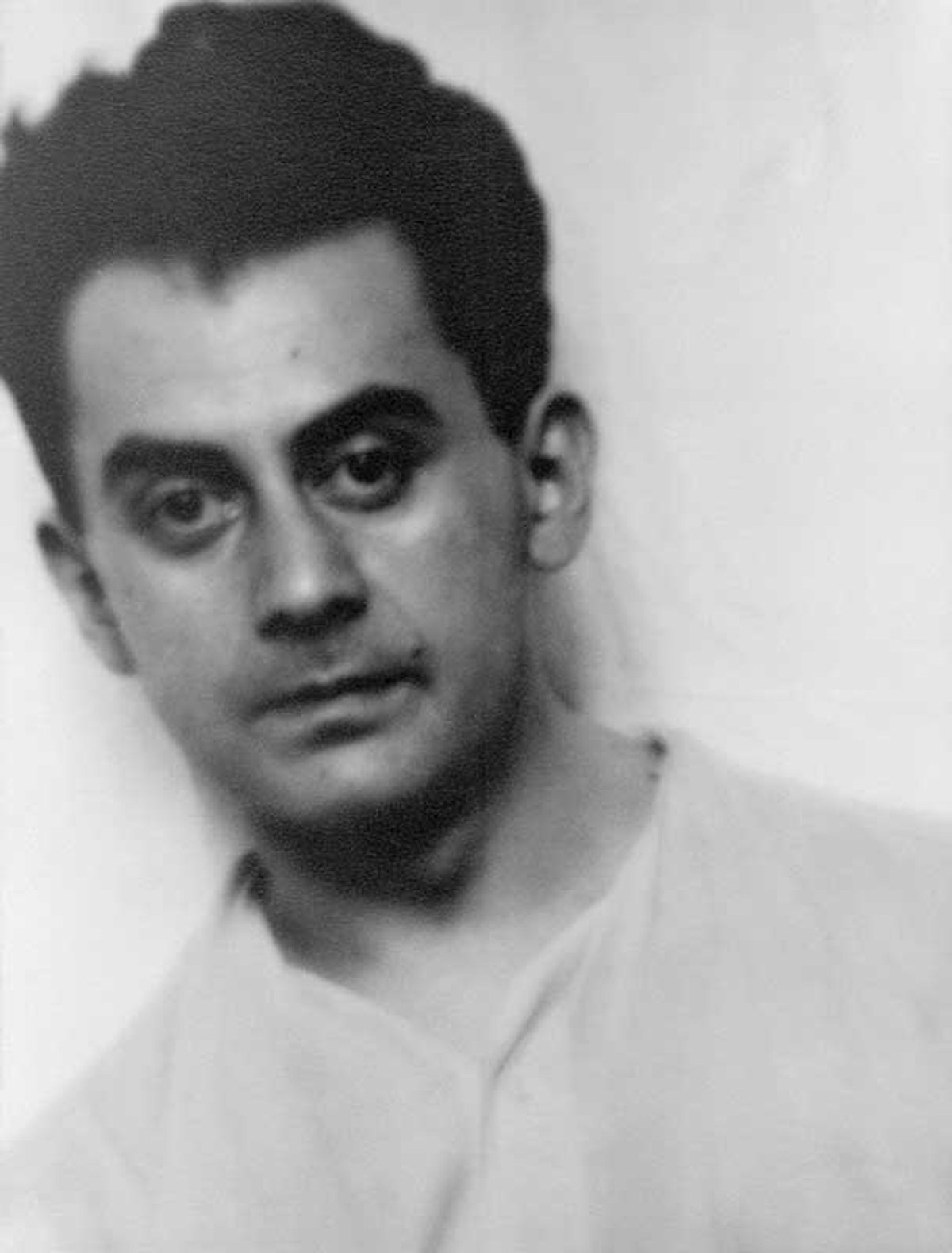

Impish, defiantly self-contradictory, sometimes obscene, Man Ray (1890-1976) resisted being understood. The painter and photographer undervalued much of his own work, such as the probing portraits that paid the bills in Paris during the 1920s and 1930s.

Arthur Lubow’s Man Ray: The Artist and His Shadows is a graceful, compact look at the man and the many kinds of art that he made, much of which manipulated light. The study is part of Yale University Press’s “Jewish Lives” series—the self-named Man Ray barely acknowledged that he was Jewish.

Shadow is a key word here. Man Ray pioneered camera-less photography in images called rayographs and solarisations, from shadows of objects on paper. Those dreamy shapes gave everyday objects a staged grandeur. He made photographs in the shadow of painting, his professed vocation, while his early paintings were in the shadow of Marcel Duchamp. He also relegated his origins, his Jewishness, to the shadows.

Man Ray was born Emmanuel Radnitsky in Philadelphia in 1890 to Jewish parents, a tailor and a seamstress, who emigrated from Russia. Determined to be a painter, he also took to photography and to photographers exploring this still young medium.

Marcel Duchamp, the Cubist and Dadaist whom Man Ray met at an artists’ retreat in New Jersey, was his conduit to Paris, where Man Ray found a home and a shared conceptual language. Later, Surrealism’s strict rule-maker, André Breton, spoke approvingly of Man Ray as “pre-Surrealist”.

Lubow names five chapters in his short study for Man Ray’s female companions. The artist regularly offered lodging to young women who needed it. Many became his lovers, such as Kiki de Montparnasse (born Alice Prin), the brazen performer and the model in so many of his photographs. Their bond was as madcap as any screwball comedy. Man Ray’s images of her, such as Le Violon d’Ingres (1924), where he super-imposed f-holes as if her body were a musical instrument—resonating with innuendo—are images that define that era. Sex in his work and the subject of who was whose muse will keep scholars busy.

Man Ray parted with another lover, the Guadeloupean dancer Adeline Fidelin, when he acknowledged his Jewishness enough to flee Nazi Germany’s invasion of France. He ended up in Los Angeles, where he found a new wife and few fans, and worked on repainting paintings that he had left behind. After the war, New York was art’s capital. The Abstract Expressionism of Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko never spoke to the witty, conceptual Man Ray, who returned to Paris. There, while Duchamp gave up making art, Man Ray burrowed into his studio—stuck in an idea of Paris that was no more.

Lubow’s evocation of Man Ray is full of insights, often dramatic, and is heartfelt on the artist’s friendship with Duchamp, but it breaks no new ground. The few images fall far short of Man Ray’s massive output. Also, Man Ray’s Jewishness was scrutinised in Alias Man Ray, an exhibition and rigorous catalogue by the Jewish Museum, New York, in 2009-10. So far, Man Ray still frustrates those who want to bring him out of the shadows. They’ll keep trying.

• Arthur Lubow, Man Ray: The Artist and His Shadows, Yale, 216pp, 30 colour + 1 b/w illus., £16.99 (hb), pub. 14 September 2021 (US), 9 November 2021 (UK)