The email message “It’s leprosy! Hurrah!” sent from Canterbury to Toronto last September was as joyous as it was brief. It solved a centuries-old puzzle and opened up a lost medieval world in glorious colour.

The sender was Leonie Seliger, the glass conservator of Canterbury Cathedral, who had discovered leprosy spots on a figure depicted on the cathedral’s 12th- and 13th-century Miracle Windows. The recipient was Rachel Koopmans, a medieval historian at York University in Toronto, with whom Seliger is studying the windows’ graphic motifs. Together they are finally identifying the original narrative order of the stained glass, unravelling stories from the years after Thomas Becket, the Archbishop of Canterbury, was murdered in the cathedral by knights of King Henry II in 1170.

“It’s very exciting to discover things that nobody had seen probably since the medieval period,” Seliger says. “And there are so many more treasures to be discovered.”

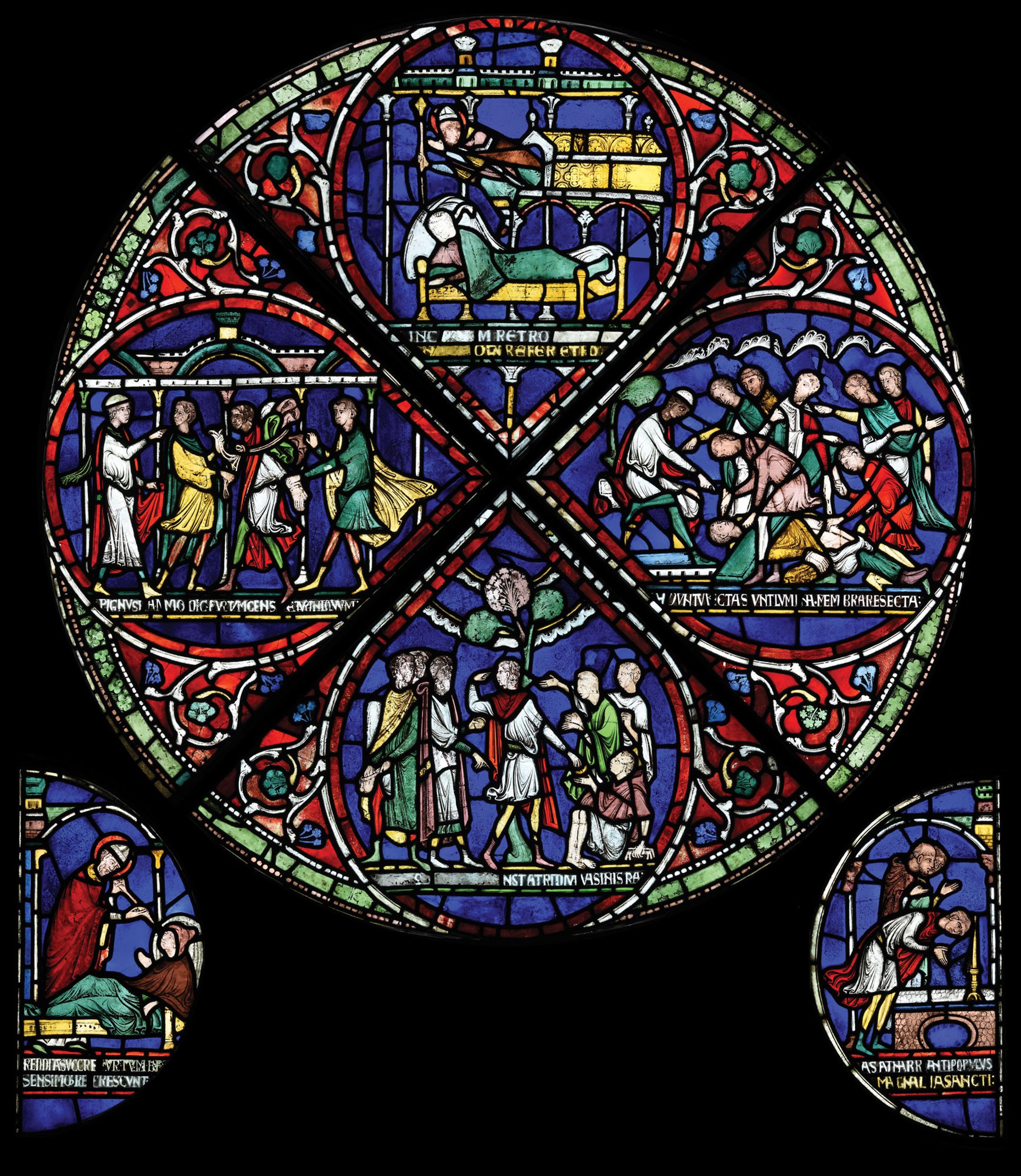

Becket was enshrined in Canterbury Cathedral’s Trinity Chapel, surrounded by 12 windows to the north and south commemorating his life and the miracles associated with him. Seven have survived, showing the early pilgrims who visited his shrine to be cured. Now an entire 6m-high window, North III, is going on exceptional loan to the British Museum in London, as the centrepiece of the forthcoming exhibition Thomas Becket: Murder and the Making of a Saint (20 May-22 August). Thanks to new research, it will be reassembled correctly for the first time in centuries.

The Miracle Windows on the southern side of Trinity Chapel at Canterbury Cathedral depict the healing miracles that are said to have taken place at the tomb of St Thomas Becket in the Crypt between 1170 and 1220 Photo: David Iliff

Armed with a microscope and a late 12th-century chronicle, Seliger and Koopmans discerned leprotic spots on a man having his legs washed—distinguishing them from corrosion marks on the glass. He could suddenly be matched to the Latin inscription “lepra” beneath a figure on horseback in another part of the window. So emerged the story of the healing of Ralph de Longeville, recorded in 1171-72 by a monk, Benedict of Peterborough, whose exhaustive account of St Thomas’s miracles is being translated by Koopmans.

“A whole lot of pieces of the puzzle clicked together,” Koopmans says. “For years we’ve been puzzling about them, and it was only when we combined my knowledge of the text and Leonie’s knowledge of the panels that the whole story became clear.”

Researchers realised this panel depicted Ralph de Longeville being healed of leprosy, a miracle associated with St Thomas that was documented in a manuscript by the monk Benedict of Peterborough © The Chapter, Canterbury Cathedral

A detail of the panel showing the leprotic spots on the man's leg, which were initially mistaken for corrosion marks on the stained glass © The Chapter, Canterbury Cathedral

Koopmans realised that the stained-glass artists who made North III in the 1180s were following the chronology of Benedict’s manuscript. Once the leprosy detail was discovered, another misplaced panel could be identified with the tale of Eilward of Westoning, who appealed for Becket’s help after being blinded and castrated for petty theft. Believed to be cured by the saint, he made a pilgrimage to Canterbury. The glaziers showed Eilward in front of a tree with three large flourishing leaves symbolising his restored genitals.

The story of Eilward of Westoning, who appealed for St Thomas’s help after being blinded and castrated for petty theft (above, right), shown in its full correct arrangement for the British Museum exhibition © The Chapter, Canterbury Cathedral

Pilgrims to Canterbury could buy small lead flasks of water infused with a tincture of Thomas’s blood; North III shows a monk from Jervaulx Abbey in Yorkshire drinking from such a flask. Other narratives portrayed in the window are those of Goditha of Hayes, cured of dropsy, and two lame sisters from Boxley.

Seliger and Koopmans proved in 2018 that glass panels of a different window in the cathedral, North V, were not a later restoration, as believed, but were genuine medieval compositions—the earliest portrayal of pilgrims travelling to Canterbury. But the fact that seven Miracle Windows survive for study today is itself a miracle.

Depredations over the centuries include the 1538 destruction of Becket’s tomb by Reformation demolition gangs, a botched 1660s restoration and the whim of a cathedral dean who had windows moved to be near his chair in the choir. In the Victorian era, glaziers reconstructed some panels using random fragments of glass and even painted their own inferior versions, never recording what they had done. These alterations went largely unquestioned until the 1970s.

Seliger and Koopmans have had to piece the stories together from hundreds of glass panes, but their task is far from complete. Interrupted by the pandemic, they will reconvene in the cathedral’s stained-glass conservation studio this autumn to study other scrambled and hard-to-read inscriptions.

There is no time to lose. Some of the windows are in great need of conservation, and Seliger will devote the next year to devising a programme of research, repair and restoration for which more than £1m will have to be raised.

“There is no series like this anywhere else—images of ordinary people telling the story of Becket’s early cult, so critical for English and international history,” Koopmans says. “We’ve got the chance to read this glass and understand what the medieval glaziers wanted us to see.”