He is sometimes mistaken for “that homeless guy” but prefers to be known as “Moses” or “God”. Or he will settle for “Roman Catholic cardinal”, a costume that always gets him a seat on the subway. Henry William Oelkers has portrayed characters humble and exalted over 25 years as an artist model. Most New Yorkers will never knowingly interact with these “professional muses”, but they often admire the art they inspire. A photographic portrait of Oelkers was used on the cover of David Javerbaum’s novel The Last Testament: a Memoir by God, which was turned into a Broadway play, and many art students have learned anatomy from staring at his body. He is often considered a dream subject, partly thanks to the Rorschach test that is his bountiful, bristling beard. But versatility has not protected Oelkers—or other live models, an often overlooked part of the arts community—from financial frailty during the coronavirus pandemic.

At 64 years old, Oelkers is recovering from cancer treatment and, as a result of cancelled live modelling sessions, says he owes about a year of rent. “Part of me already has a space picked out under an underpass to live in when I get thrown out,” he said after a recent gig where he posed contemplatively on a Central Park bench wearing a bottle-green velvet robe. It is a stark contrast to his homeless outfit, which he embodies so realistically that he sometimes warns studio coordinators about it in advance to make sure he gets let in the door. “I guess I’m way too close to homeless in my real life,” he added.

Oelkers is one of up to 200 people who make their living posing for artists in New York, according to community estimates, and many more who model occasionally. A survey of 20 schools and studios that used models before the pandemic shows that 45% have stopped hiring altogether. Most of the others are hiring half the number they used to, or fewer, while some have closed or relocated abroad. “I wish we were in a position where we could support more models than we do,” says Scott Robinson of the Pratt Institute. “I know more than a few must be struggling.”

Some models now pose through Zoom and fund a professional camera and lighting themselves. Nude modelling is less common online, but it happens. Oelkers knows two women who found screenshots of themselves on porn sites.

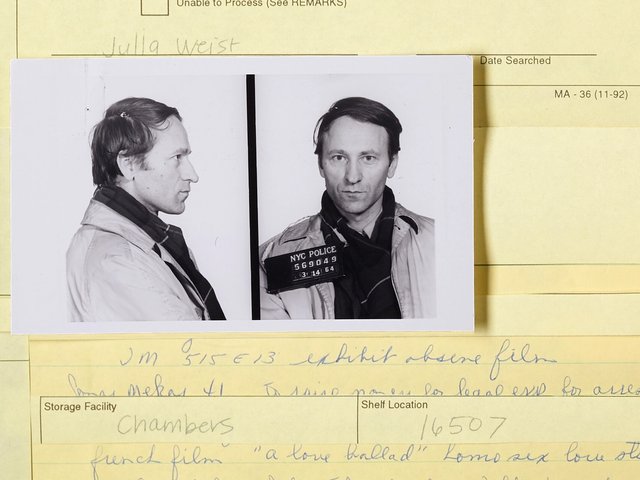

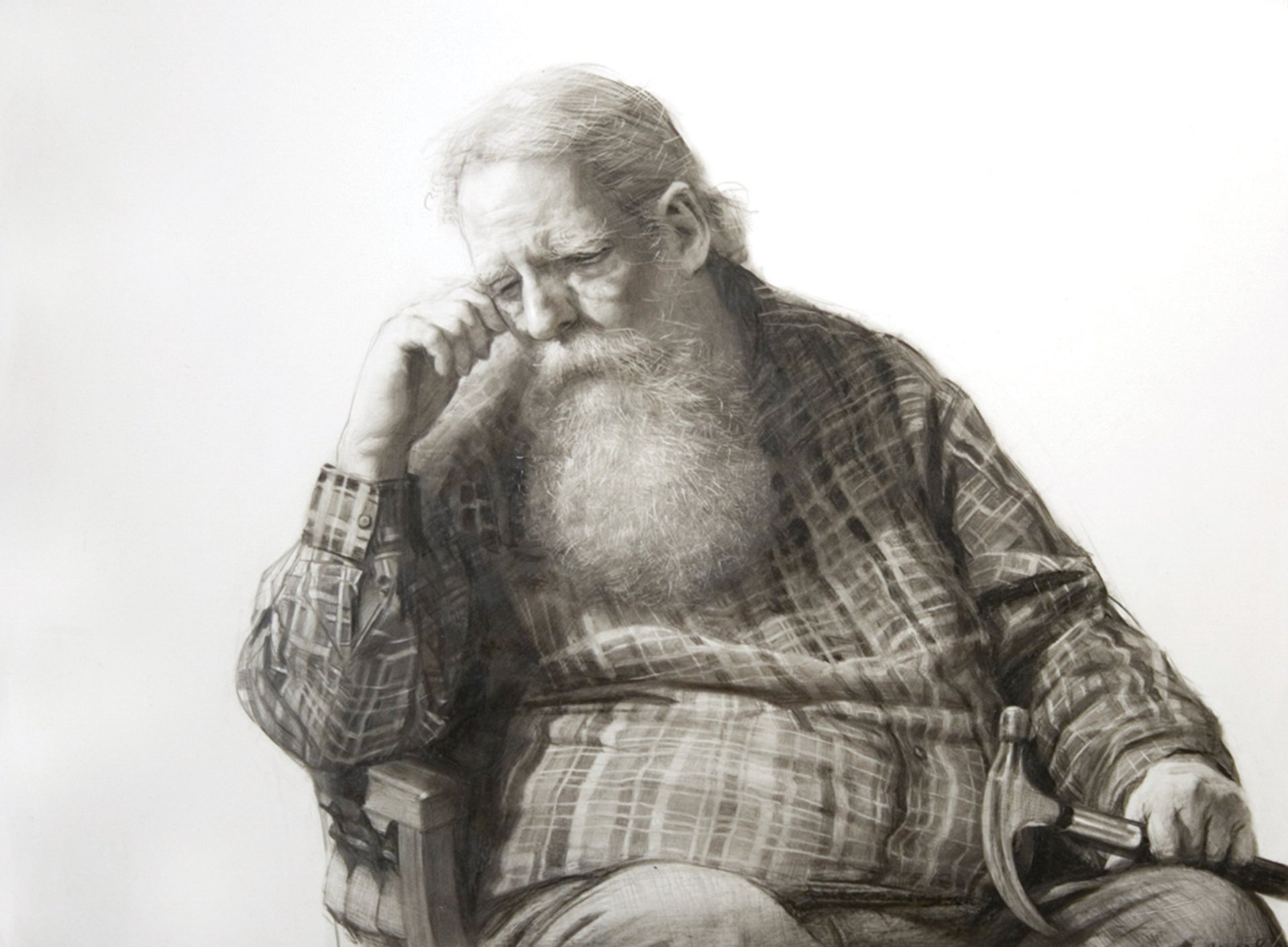

The venerable beard: Oelkers plays his part in Steven Assael’s Henry and Hammer (2020) © Steven Assael

No stimulus cheque

Art models are independent contractors who make, at most, $20 an hour. A year ago the CARES Act made unemployment insurance available to workers not on a payroll. But some have had trouble getting those benefits. Oelkers does not qualify because he did not earn enough before the pandemic—too little to pay taxes, and the minimum income requirement for federal filing is $12,000—so he is also denied the individual stimulus cheques issued over the past year. Oelkers estimates he is now making 10% of his prepandemic income.

Financial insecurity is why he fell into the art scene decades ago. He had a family to support, mounting debt, and had lost his house. On a whim, he attended modelling auditions. He was the oldest person by more than a decade and remembers standing naked alongside “surfer magazine” bodies. But he got the job, and soon learned that serious artists are not just looking to draw young, thin figures.

“You want something more,” says Richard Weinstein, a painter who Oelkers has sat for multiple times. “A few models always give us something unexpected.” Weinstein says Oelkers truly embodies his parts, allowing artists to “let their imagination buy into whatever character he’s dressed as”. Artist Minerva Durham calls Oelkers an “icon”.

Oelkers says Durham recently gave him extra money when he was recovering from cancer surgery and could not work, describing it as “severance pay”. During the pandemic, friends have been giving him food. He shops for groceries at the dollar store, hides from his landlord, and has learned how to jump the subway turnstile. He bought a belt after losing so much weight that many costumes no longer fit. He says he has had suicidal thoughts but is fighting to stay positive. He meditates daily and hopes to find a job as model coordinator. And some studios are gradually opening up.

“Do I wish sometimes that I had 30 years in a secure job? Hell, yeah!” Oelkers says. “Health insurance? Woah, baby! You know, a steady paycheque—I can’t even conceive of that right now. I swear, the rent I owe right now looks like the deficit of a third world country.”

“But this is the life I know,” he adds, “that I’ve kind of created out of desperation. And along the way, I discovered I was good at it.”