The artist Julia Weist is rethinking the role of public art and, with it, what the public offers artists. Although her stint as Public Artist in Residence (PAIR) for the for New York’s Department of Records and Information Services (DORIS) began before lockdown shut down the city—and with it, many of the parks and squares where public art can be found—she had been working in isolation for months in the municipal archives, dredging up examples of artists whose work, even if little known, has helped shape the city’s cultural landscape through government-sponsored programmes.

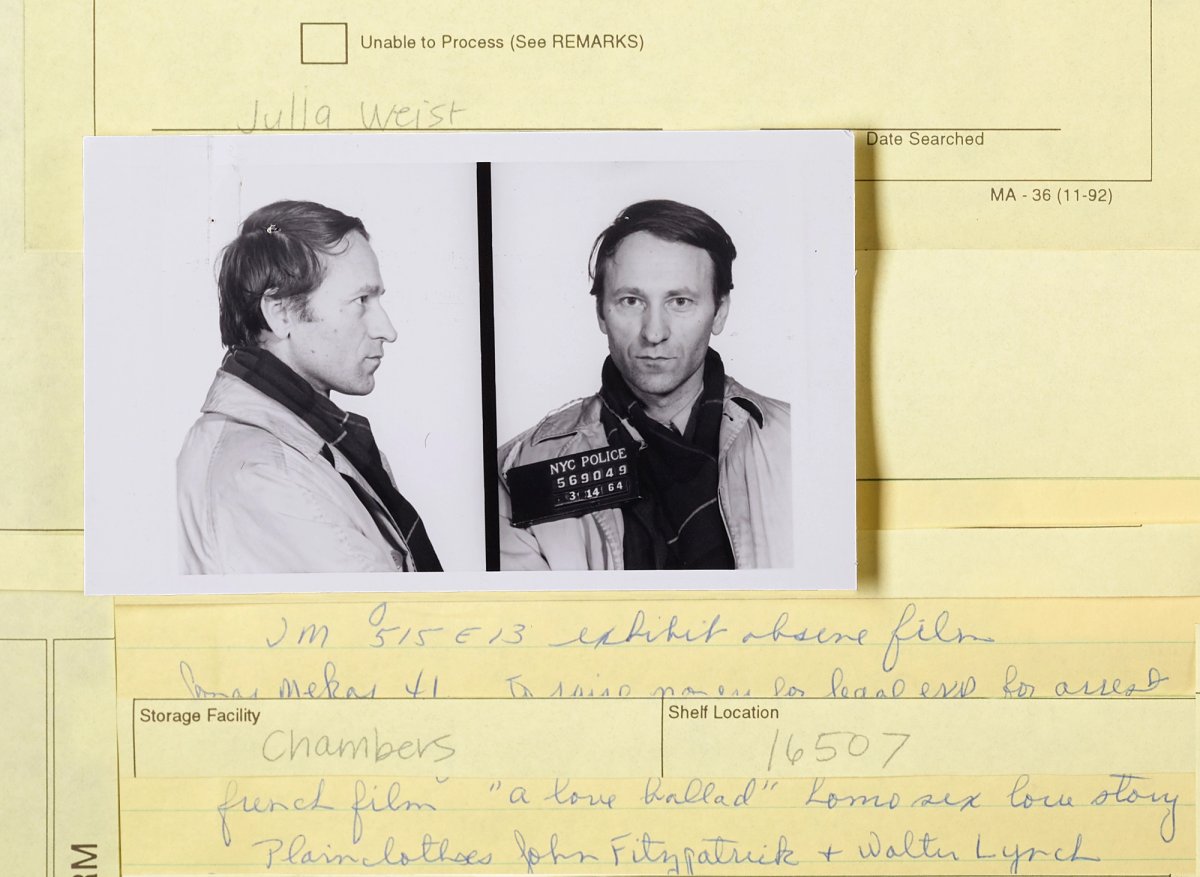

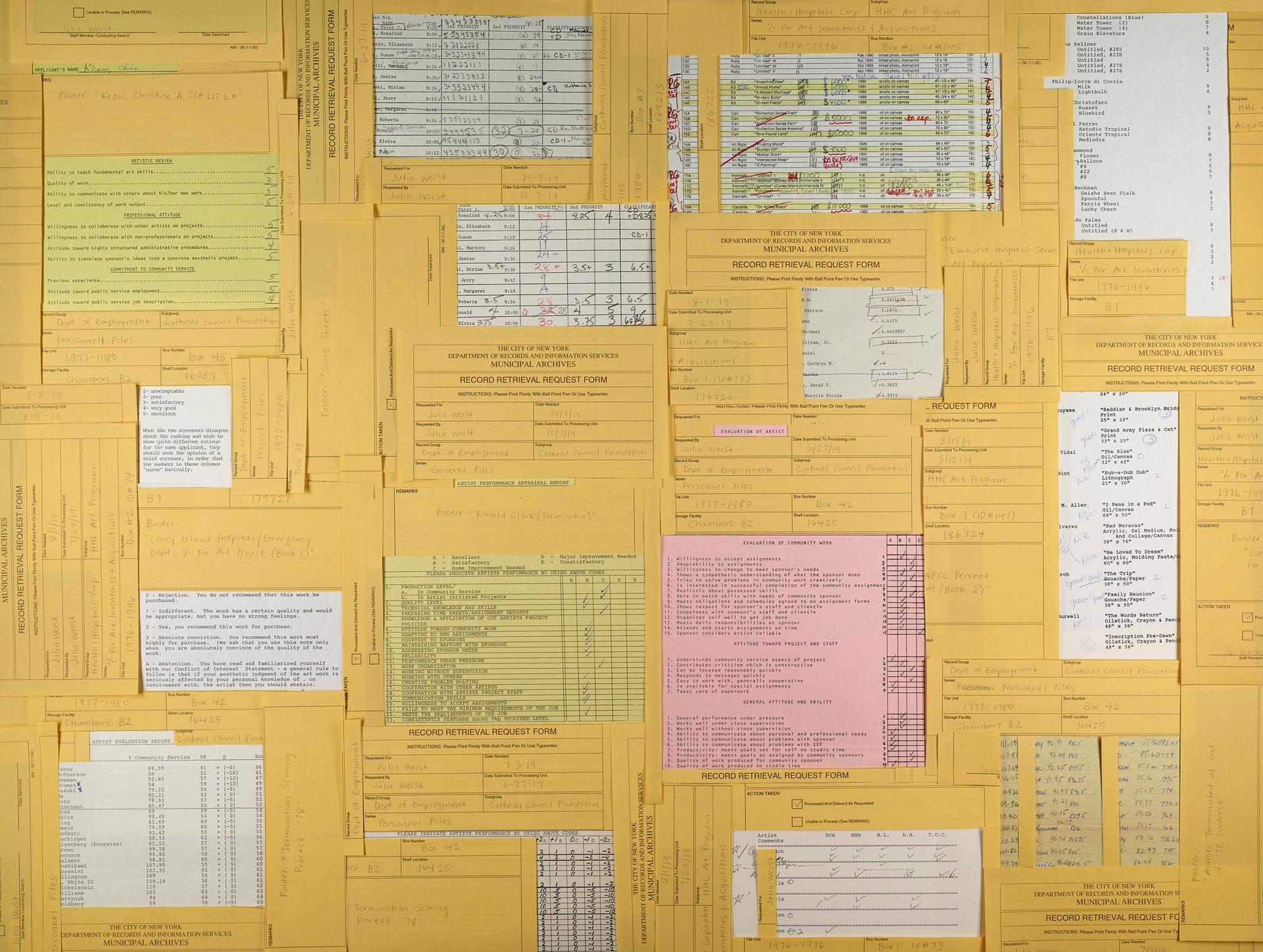

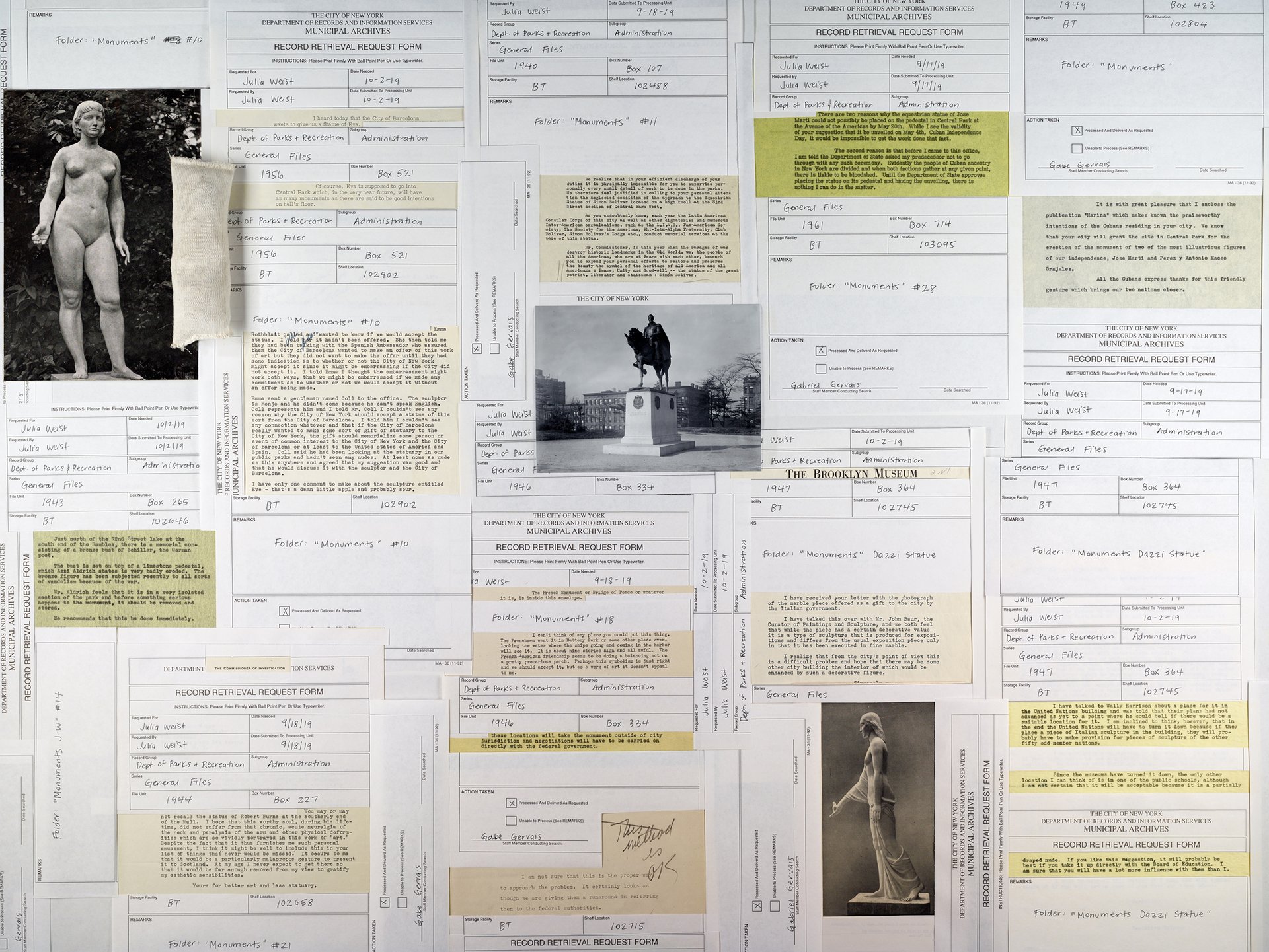

Her resulting project is partly archival, partly participatory. Entitled Public Record, it represents the culmination of Weist’s year-long residency and consists of 11 individual photographic prints submitted to DORIS as official correspondence. Her compositions were created by overlaying archival items with retrieval slips, leaving only essential sentences visible. Once the photographs of the collages were complete, she transferred a print of each to the Commissioner of DORIS with a simple memo attached: “I’ve completed eleven artworks in a series called Public Record.” As of this week, the digitised artworks, themselves now embedded in the bureaucratic structure in which she was working, are available for free for anyone if they submit a Freedom of Information Law (FOIL) request by following the instructions on the archives.nyc project page.

Rubrics, a photographic work by Julia Weist, part of her Public Record project © Julia Weist

As the coronavirus (Covid-19) pandemic pushes people online for most human interactions, Weist sees it as an opportunity to reclaim the digital commons for the people. These municipal records, she says, are owned wholly by citizens and made available for the public’s benefit.

“Typically public art utilises shared physical infrastructure such as parks, plazas and sidewalks. I'm interested in spaces owned by the public that may be abstract or immaterial,” Weist explains, adding that this project asks New Yorkers to consider two such alternative public sites. “The first is the public record, meaning all information that's already public or that can be made public according to laws and protocols. The second is the only truly public space on the internet: government websites and platforms. Although the internet is a public commons—a place where the public gathers—it's made up of privately owned and operated sites.”

A warehouse for New York’s Department of Records and Information Services Photo: Julia Weist

As her work now lives sandwiched between both physical and digital documents related to everyday life in the city, such as birth certificates, court documents and old wages ledgers, Weist was confronted by the uneasy relationship between art—and the artists who make it—and the city. While it is evident that New York’s municipal government has historically understood the value that art offers the city, one of the most culturally dense in the US, Weist says it was less clear what the city offers back to artists.

She describes decades-old records in the Department of Employment’s collection that stated: “Even prosperous economic times may find up to an estimated 75% of the work force in arts professions unemployed.” These statements are even more haunting now as 95% of artists report having lost work due to the pandemic. A few notable public work programmes show up, such as the Works Progress Administration (WPA), established in the 1930s, and the Comprehensive Employment and Training Act (CETA) in the 1970s, each of which could provide models for economic recovery for artists and cultural workers at large in the months ahead.

International, a photographic work by Julia Weist, part of her Public Record project © Julia Weist

But Weist says mostly the records are exhaustive in their documentation of art workers struggling to survive in New York. “Artists are defunded, victimised, rejected and evicted,” she writes in an essay about Public Record. “They are turned in to the House Un-American Activities Committee and are surveilled by undercover NYPD “Red Squad” officers who infiltrate their gatherings and find them subversive and obscene.”

It is evident that New York City has become increasingly unsustainable for artists as well as small arts organisations and galleries, but even more so in a massive economic emergency. “I believe that even before the pandemic the time was ripe for a massive municipal work project for artists,” Weist says.

Julia Weist at New York’s Department of Records and Information Services Photo: Kelly Marshall

Weist was one of four artists placed in residence this past year with NYC agencies as part of PAIR, an increasingly rare example of a government-funded art programme in th US. It was inspired by the artist Mierle Ukeles’ pioneering artist residency with the New York Department of Sanitation, which started in the late 1970s and indelibly changed the state of the city’s sanitation for the better. Since its launch in 2015, PAIR partnerships have included Tania Bruguera with the Mayor’s Office of Immigrant Affairs, Onyedika Chuke with the Department of Correction (Rikers Island) and Janet Zweig with the Mayor’s Office of Sustainability, among others.

It is through such works projects that artists' public contributions are recognised and supported through commissions, community projects and partnerships. In turn, artists receive consistent direct funding at a liveable wage, according to Weist. “Individual grants, commissions and market opportunities exist for artists in the city, but not at a scale that can support a robust class of artists working primarily as artists.”