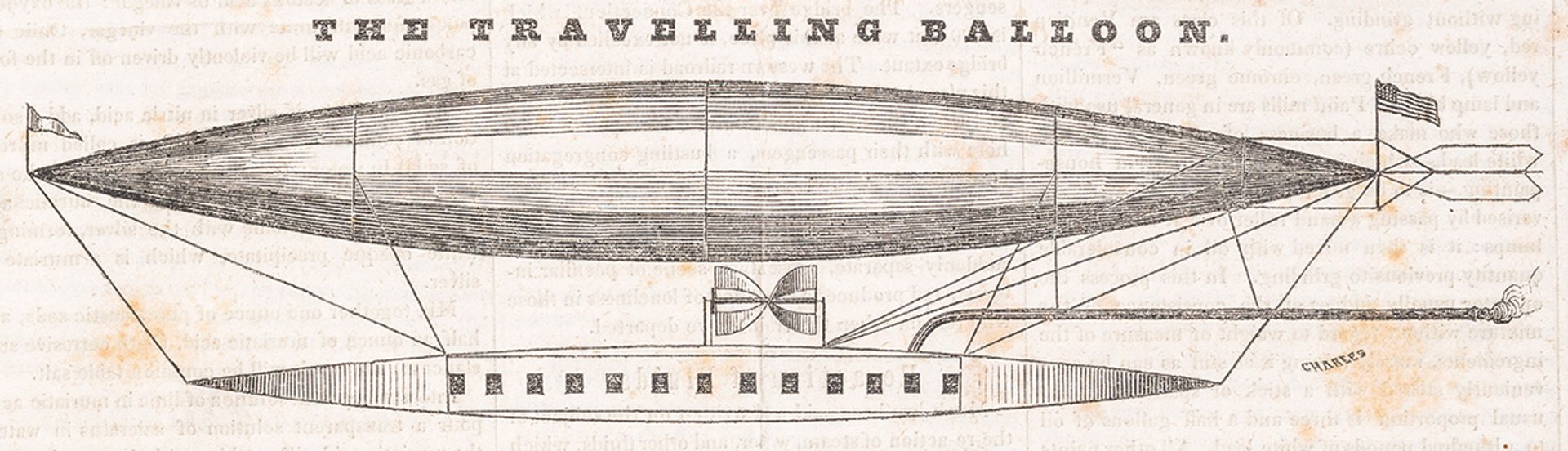

On Thanksgiving Day 1852, the New England artist and inventor Rufus Porter was visited “by swarms of thanksgiving citizens” eager to inspect his steam-powered, hydrogen-filled “travelling balloon”. Among those citizens, he later wrote in the Aerial Reporter, his self-published newspaper, were some “thanksgiving rowdies”, one of whom tested the balloon’s strength by making a hole in it. Days later, wind and rain exacerbated the damage.

Porter’s airship never did fly, nor ferry settlers across America to California as he intended. Neither did any of his other inventions—including a horse-powered boat, a revolving rifle, a self-adjusting cheese press and a “combined chair and cane”—make it to production. Despite his restless imagination, he was a chronically inept businessman. His work as an artist, which comprised creating elegant murals for New England homes and a charming line in miniature portraits, remains little known. Arguably, Porter’s most enduring achievement is the founding in 1845 of Scientific American, still the longest running magazine in the US; after only a few months, however, he had sold his share in it and moved on to new interests.

“Porter recognised the transformative potential of technology to bring people together”

Porter does not deserve to be ridiculed, even if he was sometimes taken less than seriously during his lifetime. (In 1849 the lithographer Nathaniel Currier published a satirical print, The Way They Go to California, which showed eager goldminers swinging their picks off the side of a dirigible that uncannily resembles Porter’s.) Rufus Porter’s Curious World, a new exhibition of paintings, inventions, publications and ephemera at Bowdoin College Museum of Art and a book published by Penn State University Press, will set forth the case that this American polymath was, in many respects, decades—if not centuries—ahead of his time.

“Porter recognised the transformative potential of technology to bring people together,” says Anne Collins Goodyear, the co-director of the Bowdoin College Museum of Art. “He was someone who envisioned the power of a network to share information.”

Justin Wolff, the co-organiser of the exhibition and a professor of art history at the University of Maine, quotes the author Jean Lipman, who called Porter a “mechanical Johnny Appleseed, sowing the seeds of new and ingenious ideas”. Wolff says: “He had a very devoted love of public knowledge, of useful knowledge.”

Porter's 1845 design for a “travelling balloon” Courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society

Porter sought to share that knowledge not only through his various publishing endeavours, but also through the development of his “aerial steamer”. When, in another piece for the Aerial Reporter, he anticipates the potential benefits of air travel, he describes a future that would not fully arrive for another 100 years: the faster dissemination of news around the globe; the importation of out-of-season fruits and vegetables; and the migration of people keen to avoid inclement winters or summers. Even more optimistically, he prognosticates: “The social habits of mankind will be promoted… and systems of laws and customs, more in accordance with common sense and common comfort, will prevail throughout the world.” He was a true believer in the American Enlightenment.

Born into a farming family in Massachusetts in 1792, Porter moved to Maine when he was nine. Although he briefly attended Fryeburg Academy, as an artist and engineer he was largely self-taught. His miniature watercolour portraits—a number of which are gathered for the exhibition—while deftly executed, were a commercial side-line, apparently devised to raise funds for his inventions. But to designate Porter as a folk artist is problematic, says the show’s co-curator Laura Sprague. “It puts him into a silo, [it is] a very constricted way of understanding him,” she says. “He did all of these things simultaneously.”

A portrait of Martha Swan Flagg (around 1830) attributed to Rufus Porter © Private Collection; Photo: David Bohl

Wolff points out, as an example, how Porter’s work in mechanics, engineering and spatial design fed into his skills in composing murals for domestic spaces. In one of his finest works, known as the Howe House Mural (1838), an excised panel of which appears in the exhibition, Porter and his son Stephen fitted a multi-perspective landscape between doors and windows in a stairwell.

Since Porter’s time, such cross-disciplinary thinking has fallen out of favour, a trend that the exhibition’s organisers hope to challenge. “In an age in which Stem—science, technology, engineering and mathematics—takes centre stage in education,” says Goodyear, “we are interested—especially in a liberal arts college like Bowdoin—in foregrounding the importance of arts and humanities in thinking constructively about the future.”

The exhibition’s main sponsor is The Wyeth Foundation for American Art.

• Rufus Porter’s Curious World: Art and Invention in America, 1815-60, Bowdoin College Museum of Art, Brunswick, Maine, 12 December-31 May 2020