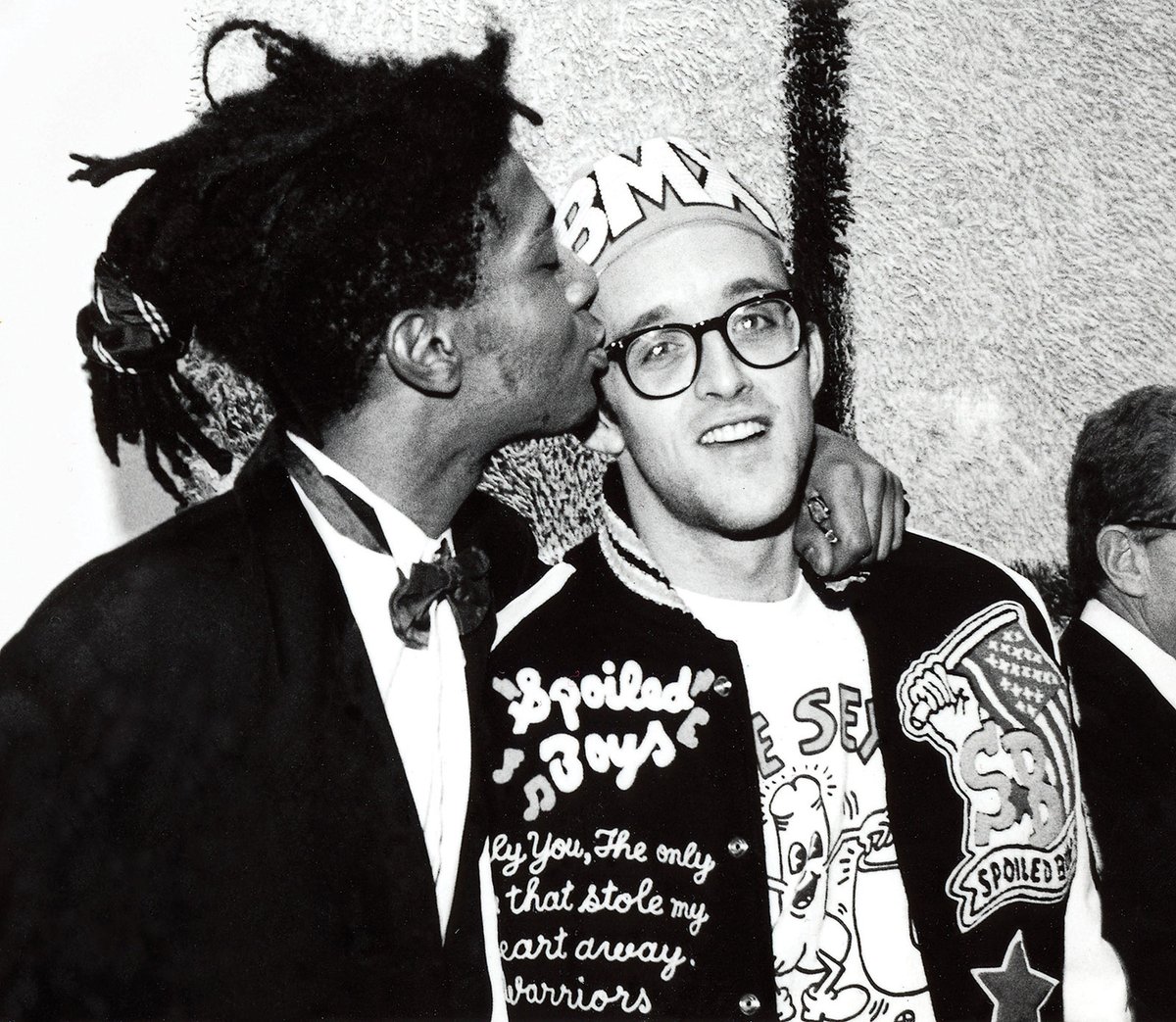

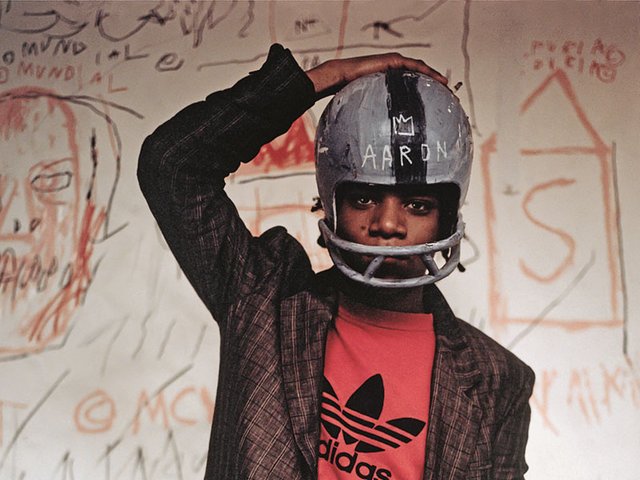

Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat were born two-and-a-half years apart and died young: age 31 and 27 respectively. They lived and worked in the gritty streets of lower Manhattan in the 1970s and 80s. They partied and worked with Andy Warhol. They were DJs, friends, mutual admirers and rivals. At first, the streets and subways of New York City were their gallery walls, and their messages were overtly political. When they died they were famous. Today, they are megastars.

Given the parallels between Haring and Basquiat, the Austrian curator and art historian Dieter Buchhart still wonders why Keith Haring, Jean-Michel Basquiat: Crossing Lines, which opens at the National Gallery of Victoria (NGV) this week, is the world’s first substantial art museum show to examine the commonalities and divergences between the work of two young men whose early deaths belied their vast, varied and influential legacy.

“This is definitely the first big museum show of the two artists together,” Buchhart says. “I had this idea for a long while, because Haring and Basquiat were dear friends [but] they were also rivals, and that meant that they tried to get better [by competing with each other].”

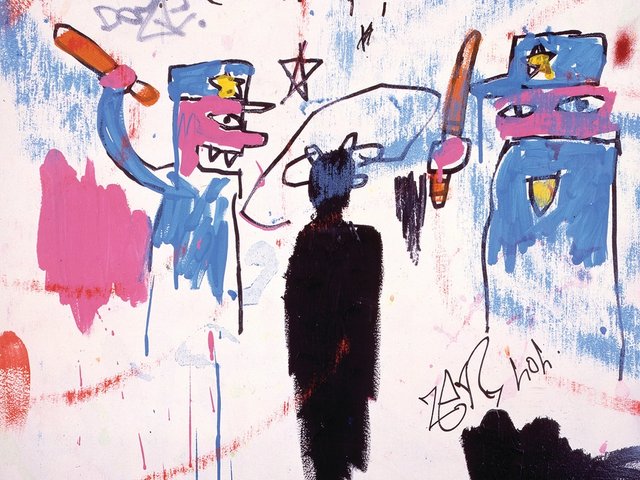

Basquiat’s Untitled (1982) © Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat

Buchhart still remembers the day in the 1980s when a school classmate returned from a trip to New York bearing some Haring works on paper. The classmate had bumped into the artist in Manhattan, and Haring had given him some drawings. They fascinated Buchhart. Today, he is an acknowledged scholar on both Haring and Basquiat.

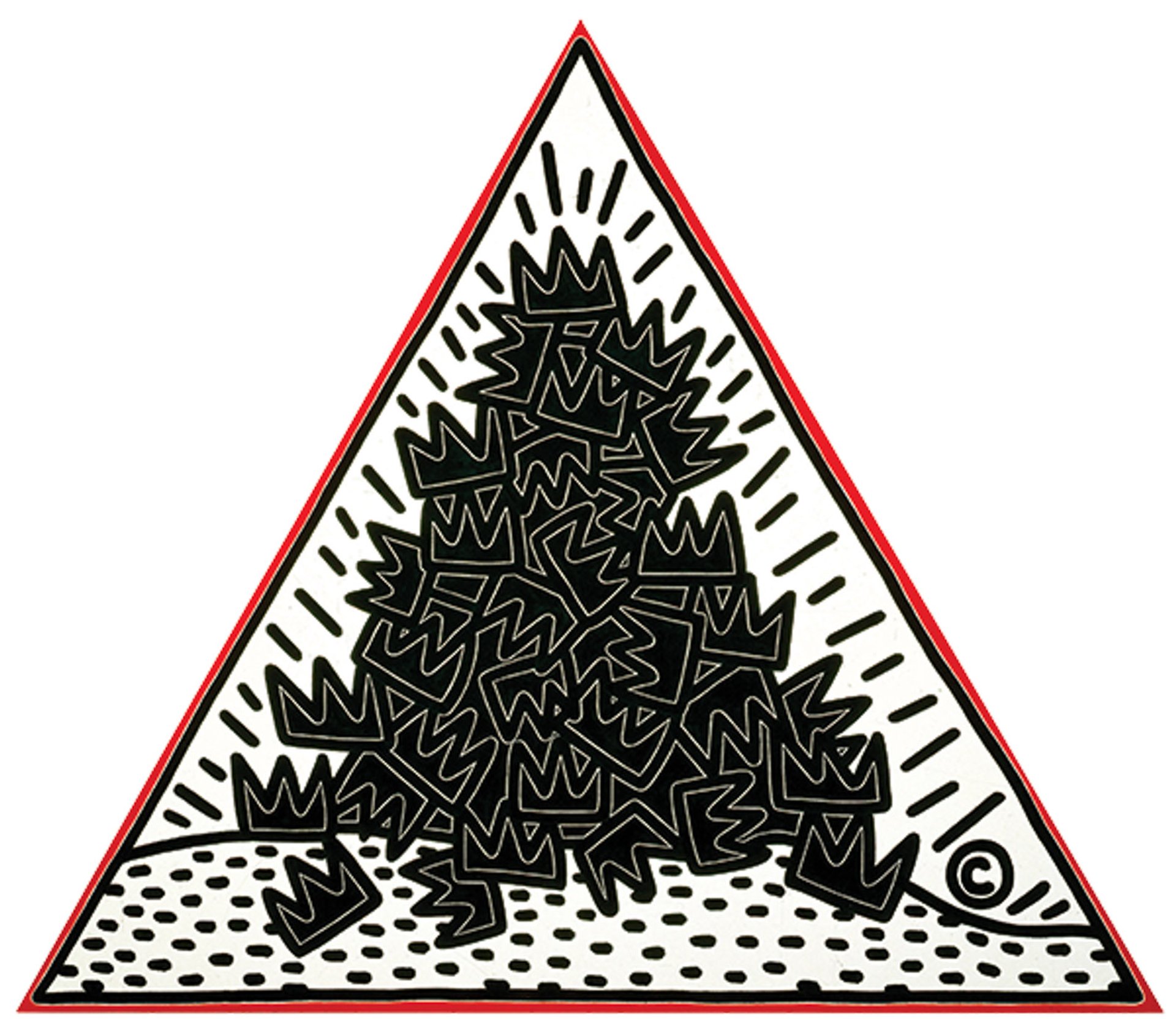

Manhattan in the 1980s was nothing like the glass-and-steel showpiece it is today. It was an “inspiring warzone”, where cheap rents attracted young artists, Buchhart says. It was here that Haring developed characters such as the Barking Dog and the Radiant Baby, while Basquiat produced his complex layering of motifs and symbols. Their art was against racism, commodification and oppression. Tragically, both men died from two of the major scourges of the times: Haring of HIV/Aids-related cancer and Basquiat of a drugs overdose.

Haring’s A Pile of Crowns for Jean-Michel Basquiat (1988) © Keith Haring Foundation

Why Melbourne for this ground-breaking show? Buchhart points out that Haring had links to the city, painting a recently restored mural as well as an ephemeral work on the NGV’s glass facade. While Basquiat never visited Melbourne, the NGV’s 2015-16 exhibition featuring Andy Warhol and Ai Weiwei started a tradition of creating shows with two artists. “The format made sense here,” Buchhart says, adding that the 300 works in the show will include Basquiat’s “undisputed masterpiece”, Untitled (1982), and an untitled Haring painting on a tarpaulin featuring an atomic mushroom, babies and angels.

Basquiat’s estate is run by his family. Haring had time to set up the Keith Haring Foundation, located in his studio in Manhattan’s NoHo area, which is lending 30 to 40 pieces to the NGV show. Gil Vazquez, the foundation’s president, was a close friend of Haring’s and remembers the artist was a “huge fan” of Basquiat, and had a Basquiat in his bedroom: Defacement (The Death of Michael Stewart), the 1983 painting about Basquiat’s friend who died after being arrested for tagging a wall.

The Haring archive is huge and includes the artist’s library, newspaper clippings, catalogues, apparel, photographs, letters, music and the files he kept on people who interested him—including Basquiat. “He had drafts of things he wrote about Jean-Michel after he passed,” says Anna Gurton-Wachter, the foundation’s archivist. These include the draft of an article he wrote for Vogue, which is included in the exhibition.

The exhibition’s main supporters are Creative Victoria and Mercedes-Benz.

• Keith Haring, Jean-Michel Basquiat: Crossing Lines, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 1 December-11 April 2020