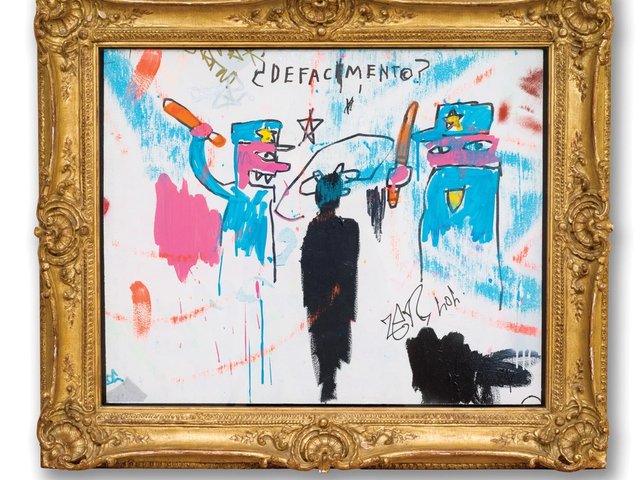

In September 1983, deeply shaken by the fatal beating of his friend and fellow street artist Michael Stewart while under arrest, Jean-Michel Basquiat went to Keith Haring’s studio at 600 Broadway and scrawled his reaction directly onto the wall. The painting, which Haring named Defacement (The Death of Michael Stewart), depicts two ruddy-faced NYPD officers wielding bright orange batons in the face of a black figure.

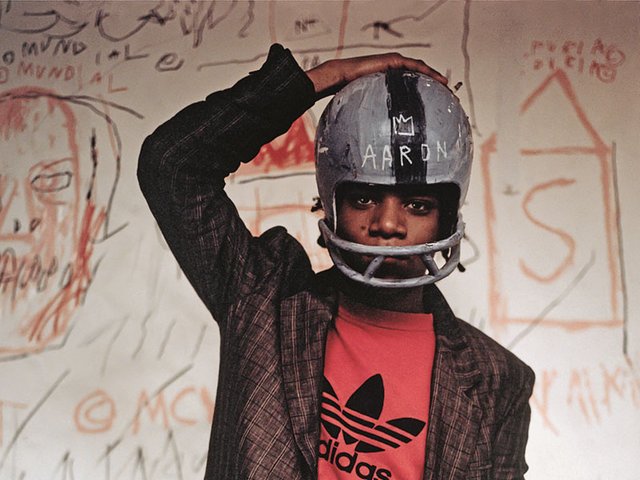

“At the time, Basquiat said ‘it could have been me’. Michael’s death was so traumatic he felt paralysed by it,” says the activist and writer Chaédria LaBouvier, who has organised an exhibition dedicated solely to Defacement at her alma mater, Williams College in Massachusetts (until 29 January). “Basquiat’s last live-in girlfriend Kelle Inman said that Defacement was a painting that really touched him. They were still talking about Michael Stewart five years after his death.”

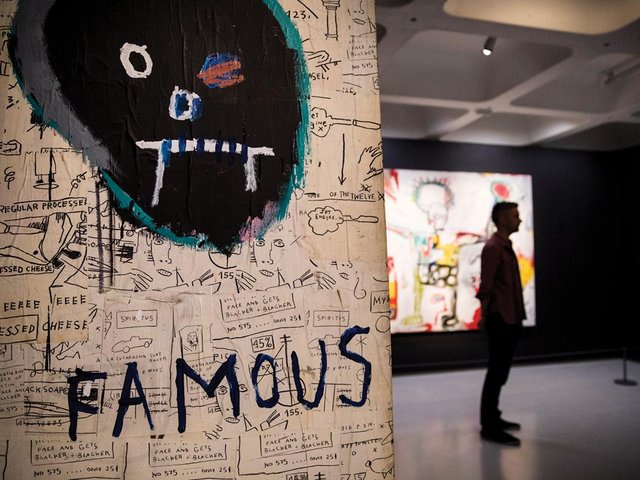

There has been little scholarly research on Defacement, largely because it has only been exhibited twice before: in 2001 and again in 2014-15. It is currently on show in the recently refurbished reading room at Williams College Museum of Art (WCMA) and is the subject of a new course being taught at the liberal arts university by LaBouvier in January.

“There’s a dearth of scholarship on Basquiat in general; his work didn’t fit comfortably into the categories that were created for American art in the early 1980s,” says Jordana Moore Saggese, a professor of visual studies at California College of the Arts who spoke at a symposium about Defacement on 10 November. “Around 90% of his works are in private collections, which also makes research difficult.” Another personal collection of around 30 works, created by Basquiat between 1979 and 1981 in the Manhattan apartment of his friend Lonny Lichtenberg, are on show at Miami’s satellite fair, X Contemporary, for the first time. Meanwhile, there are plenty of works by Basquiat on show at Art Basel in Miami Beach at galleries including Van de Weghe, Gagosian and Helly Nahmad, who sold one painting for $15m this week.

“We’re in this together” Defacement has always been kept in an intimate environment. Haring cut the work from his studio wall around a year after it was painted and hung it over his bed in an elaborate, baroque-style frame sourced by Yoko Ono’s then boyfriend, the interior designer Sam Havadtoy. The work remained in Haring’s possession until he died in 1990, when it was given to the Italian curator Francesco Clemente’s daughter, Nina. Despite the age gap, she was a close friend of the New York artist and still owns the work today. “Keith specifically left it to Nina; he thought she would know what to do with it,” LaBouvier says. “Nina grew up looking at this painting every day.”

LaBouvier also grew up with Basquiat’s work: her parents were not wealthy collectors, but kept three of his drawings in the family home. She has been researching the artist’s life and work since she was 19. The current project, however, is particularly poignant for LaBouvier, whose brother Clinton Roebexar Allen was shot dead by Dallas police in March 2013. The same month she co-founded Mothers Against Police Brutality and has since become a vocal proponent of the Black Lives Matter movement.

“I feel that the art world has not asked itself sufficiently enough if black lives matter,” LaBouvier says. “Places where we create culture matter so much; art reflects how we see ourselves or how we want to see ourselves. The Defacement project combines my scholarship and activism in a place where it is sorely needed.” There are plans to exhibit the painting at other institutions in the US, possibly with other works that were created in relation to Defacement. In 1985, Haring painted Michael Stewart—USA for Africa, depicting a blood-red naked man being strangled by a pair of disembodied pink hands.

The November symposium, which addressed issues of police brutality, black masculinity and racism, is one of many conversations that have been ignited by the Defacement exhibition. Following an open call, individuals and groups, including the Black Student Union at Williams College and detectives from the New York Police Department, have held discussions in the reading room. Original copies of the New York Times from the day after Michael Stewart was beaten have been left in the space, which has been furnished with couches and bookshelves to resemble a living room.

“With Defacement as a centrepiece, the reading room has become a public platform to hold really difficult discussions. The work was painted 33 years ago, but it reminds us that these are not new conversations we are having,” says Sonnet Coggins, WCMA’s associate director for academic and public engagement.

A private reaction At the time, Michael Stewart’s death prompted public outcry, stirring protests by black activists and others who believed that New York City officials had covered up the actions of the transit police. (In 1985, an all-white jury acquitted all six of the indicted officers.) However, Basquiat avoided these rallies, choosing instead to paint Defacement behind closed doors. “We are seeing a very filtered and private meditation that wasn’t supposed to be public; Defacement wasn’t supposed to be part of a marketplace or discourse,” LaBouvier says. “Artists often gave each other gifts and these gifts were sacred, they were not part of the commercial world.”

LaBouvier argues that another painting by Basquiat in the collection of the Brooklyn Museum is the artist’s “public commentary” on Stewart’s death. Back of the Neck, which was begun in 1982 but finished in 1983, is a semi-anatomical painting of a neck, spine and an arm bent at a 90-degree angle, “like it could be part of a choke hold”, LaBouvier says. Stewart’s death prompted a review of the NYPD’s use of restraining manoeuvres that cut off the flow of blood and oxygen to the brain, which were banned in 1993.

Franklin Sirmans, the director of the Pérez Art Museum Miami, who was the first to publicly show Defacement in the exhibition One Nation Under a Groove at the Bronx Museum in 2001, says the work is “remarkable” in the context of Basquiat’s output. “There’s this line between what is considered a work for the gallery and what is considered something that he would have done as part of SAMO [the graffiti collective with the eponymous tag],” he says. “This piece is a real reaction; it’s done with the urgency of one of his writings on the wall.”

A variety of other people’s tags are also visible on the surface of the painting, which Sirmans suggests points to Basquiat “as more of a collective person than we usually give him credit”. The fact that Defacement was painted on the wall of Haring’s studio also “places the artist within a conversation of ‘you’re not alone, we’re in this together’”, says Sirmans, who also took part in the symposium.

For LaBouvier, Defacement “is the most topical painting in Basquiat’s body of work at the moment”. It is also the most personal, as it was her brother’s death that motivated LaBouvier to create a project focusing on the painting, which serves as a memorial not just to Michael Stewart, but to Clinton Allen and all the other young black men lost to police violence. “Had Clinton not lived, this project would not have hap-pened,” LaBouvier says. “Here8’s this boy the art world would have never cared about. He lived in Dallas and wanted to be a rancher. But he is making us look at these issues and that gives me such a tremendous sense of relief and pride.”