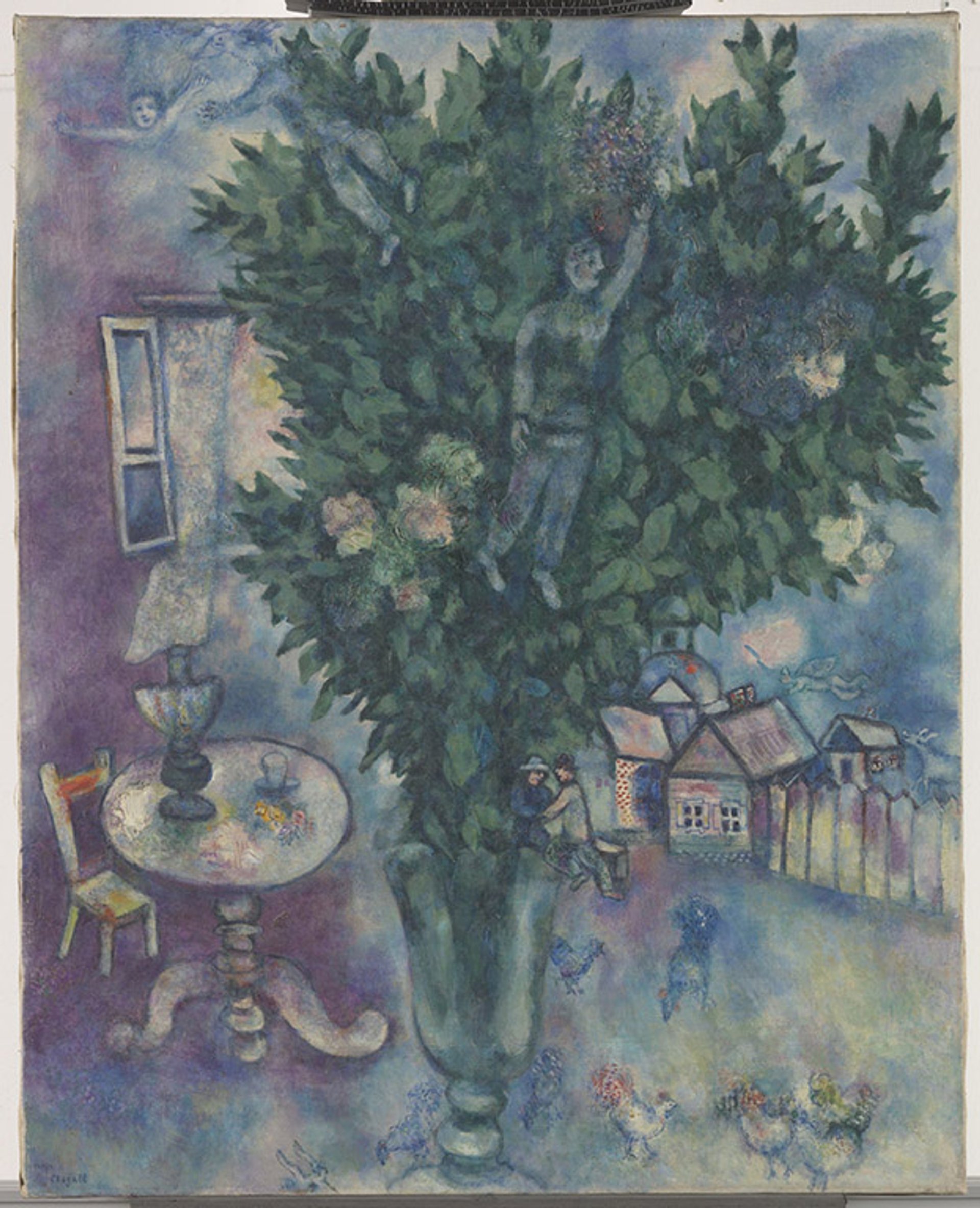

Eight years ago, Meta Chavannes, a conservator at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, was examining the 1913 Chagall painting The Pregnant Woman/Maternity in response to a loan request and was dismayed to find some cracks in its deep red background. It proved a challenge to treat, and she searched in vain for some technical literature to enlighten her on what pigment the artist might have used for that area.

“Chagall didn’t really want to talk about his working methods,” says Chavannes. “He said, ‘Look at the paintings, look at the chemistry going on, rather than trying to work out exactly how I did this.’” Nor did the artist want to be filmed when he was painting, she adds.

Chagall's The Pregnant Woman/Maternity (1913 © Marc Chagall, c/o Pictoright Amsterdam/Chagall ®

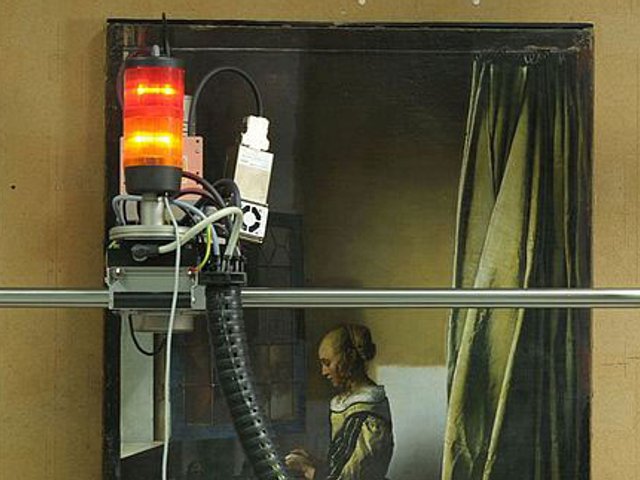

Confronting a dearth of knowledge, the conservator and her colleagues would eventually decide to take a deep dive, studying and testing nine Chagall paintings in the Stedelijk’s collection to see what they could glean about his practice. Now the museum has announced the results of that five-year effort, which could prove valuable to conservators and art historians around the globe.

“We were trying to collect really basic information about which materials, which pigments he used, which canvases he used, whether he varnished, how he set up a painting and what he was trying to achieve,” Chavannes says.

The nine paintings span 35 years of Chagall’s career. Some of the conservators’ physical findings line up with existing anecdotes about the artist’s life, like the lack of funds during the Paris years that prompted him to paint The Fiddler (1912) on a tablecloth. Conservators have determined that the chequered tablecloth is typical of those woven in his native Vitebsk in what today is Belarus and theorise that his wife, Bella, who was staying in Vitebsk in 1912, gave it to him.

“You can see the blue grid pattern below the paint, and we even found the remnants of some tassels around the edges,” Chavannes says. An inspection of the tablecloth under raking light found that Chagall used the chequered pattern as a grid for filling in the blocky houses in the composition.

Chagall's The Fiddler when raked with through-light René Gerritsen

Conservators also gained some insight into the artist’s habit of abandoning canvases and returning to them by examining The Synagogue at Safad, Israel (1931) with infrared reflectography. The test revealed an underdrawing totally unrelated to the painting’s subject. When conservators turned the painting a quarter-clockwise, they realized that the underdrawing resembled the composition in a 1924 painting depicting Chagall’s daughter, Ida at The Window. Whereas conservators had earlier assumed that he painted the synagogue on a trip to Israel, the underdrawing suggests that he probably started it when he returned to Paris, picking up a canvas he had abandoned seven years earlier.

Chagall's The Synagogue at Safad, Israel René Gerritsen

Chagall's Ida at the Window (1924) Rik Klein Gotink

Similarly, after studying the thick paint layers in The Virgin With the Sleigh, completed in 1947, the Stedelijk team conjectured that Chagall must have started it in France prior to moving to the United States and then transported it in a crate during his 1941 ocean crossing. (The artist would remain in the US until 1947, when he returned to France.)

Throughout the nine paintings, Chagall seems to have relied on the same eight pigments, which the conservation team will document in a forthcoming article about their project in the German scholarly journal Zeitschrift für Kunsttechnologie und Konservierung.

Conservators have also gained a sense of Chagall’s compositional method in the nine works, Chavannes says. Once the artist completed an underdrawing, he tended to faithfully fill in the central figure as if he were working on a colouring book. But in the background he made many more changes, removing, for example, an underdrawn figure with polka dot trousers reaching up into a tree in The Fiddler.

He often made changes in the background that resulted in “a more streamlined and less cluttered look”, jettisoning elements that “he thought maybe were too much for some reason”, the conservator says.

Some questions remain unresolved, like the cause of degradation of a layer of green paint on the leaves in Love Idyll (1925), and the reason for paint losses in The Pregnant Woman/Maternity and in Self-Portrait With Seven Fingers (1913). “It’s tempting to say they got damaged while they were stowed in a loft or under a bed in his very cramped studio in Paris, but we don’t know,” Chavannes explains.

Chagall's Love Idyll (1925) under ultraviolet light Rik Klein Gotink

The conservators hope that colleagues at other museums will put the Chagall research to use after their results are published. In the meantime, a video about the project is here, and museumgoers will have a chance to view eight of the nine paintings in the exhibition Chagall, Picasso, Mondrian and Others: Migrant Artists in Paris, opening at the Stedelijk on 21 September. Drawing on the museum’s collection, the show will feature works by more than 50 artists, photographers and graphic designers, including 38 pieces by Chagall.

“We started from scratch in uncharted territory,” Chavannes says. Now, pieces of the Chagall puzzle have finally come together.