Herb and Dorothy Vogel ©Arthouse Films/Courtesy Everett Collection Inc/Alamy Stock Photo

It feels like a bygone age. Dorothy (b. 1935) and Herbert Vogel (1922-2012) were a New York librarian and a postal worker who spent almost half a century acquiring art that they crammed into their one-bedroom apartment in Manhattan. Bought for enjoyment rather than investment, the resultant collection of more than 4,000 items, mostly works on paper, by conceptual and minimalist artists such as Carl Andre, Donald Judd and Sol LeWitt, was donated to the National Gallery of Art in Washington and various other museums throughout the US.

“It had to be affordable, and it had to be able to fit into the apartment,” explained Herbert Vogel in a 2008 interview with the Daily Telegraph.

But in an era of growing income inequality, in which the wealthy have embraced art—particularly contemporary art—as an alternative asset class, pushing gallery and auction prices ever-higher and hollowing out the middle market, is it still possible for professionals of relatively modest means to become serious collectors?

“If they exist, I haven’t seen them,” says Douglas Walla, the founder of the New York-based contemporary dealers, Kent Fine Art. “In large part, the entry part of the market for young artists, where the price point would be very accessible, has been consumed by speculators,” Walla says, adding that much of this activity is currently focused on “artists of colour—long neglected—and older women artists of merit. The endgame is profit.”

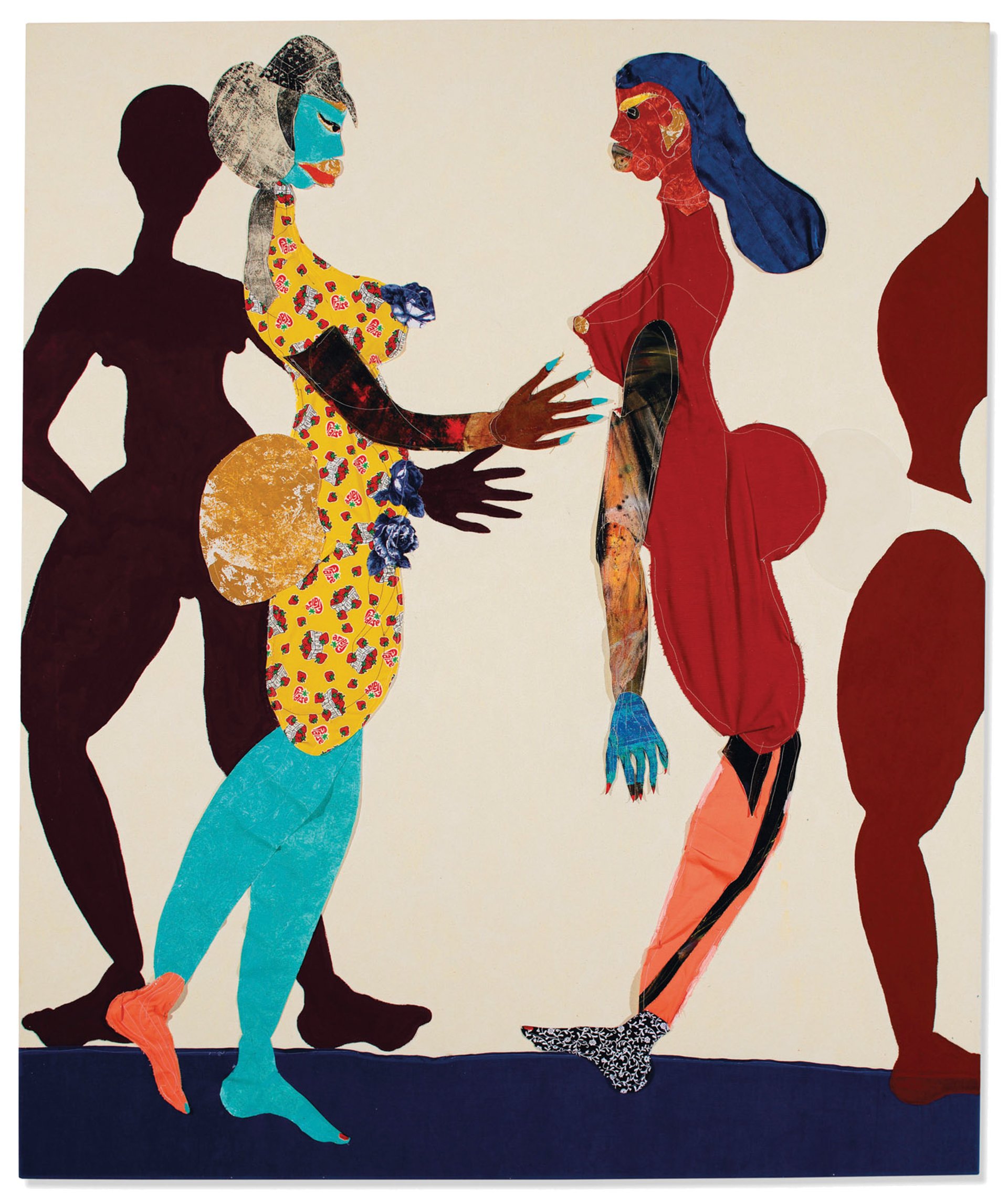

Tschabalala Self's Out of Body (2015) Courtesy the artist

The £371,250 bid by the New York-based dealer Jose Mugrabi for the 2015 oil-and-fabric collage Out of Body by the young African American artist Tschabalala Self at Christie’s in London in June—more than six times the high estimate and setting a new auction record for Self—showed the sort of profits that can be made “flipping” works by sought-after names. There is a lengthy queue of buyers for new pieces by Self, one of which sold for between $60,000 and $80,000, on the booth of the London dealer Pilar Corrias at Art Basel earlier that month.

The idea that a postal worker or a librarian might be able to collect in today’s art world seems almost laughable. But it is not just the overheated contemporary market that is suffering from a shortage of collectors from the middle or professional classes.

“So many of my clients were doctors, dentists and veterinarians,” says the New York dealer Michele Beiny, who has run a gallery specialising in 18th- and 19th-century English and Continental porcelain since 1987. “Now they tend to come from finance and real estate. It has changed.”

Even though 18th-century porcelain has become less fashionable with collectors and therefore less expensive than most 21st-century art, quality pieces in the $5,000-$10,000 range can still be out of reach. “People would love to collect but they’ve been hit by the economy,” Beiny says.

According to the report Under Pressure: the Squeezed Middle Class, published in May by the Paris-based Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, “over the past 30 years middle-income households have experienced dismal income growth or even stagnation in some countries.” In addition, “the cost of living has become increasingly expensive for the middle class, as the costs of core services and goods such as housing have risen faster than income,” the report says.

Julia Boston is the founder one of the few antiques shops left in the King’s Road in west London.

This economic squeeze has affected every sector of the art and antiques trade. “The market took a huge hit in 2008-09,” says Julia Boston, the founder of Julia Boston Antiques, one of the few antiques shops left in the King’s Road in west London. “I took the decision to have much better stock. The rich are protected from recession. The antiques trade has contracted enormously. The middle is dead,” says Boston, who specialises in 18th- and 19th-century French furnishings in the £1,000-£100,000 range.

Boston points out that nowadays successful younger professionals in their 30s and 40s “spend their money on mortgages and education”, and there is little left to spend on big-ticket discretionary purchases. She added that their homes tend to be “very minimalist, very modern.”

A shortage of disposable income and a shift to plain white interiors are two of the reasons why the professional classes are buying fewer works of art and collectables. But there are other cultural factors at play. Collecting, like many other aspects of 21st-century life, has been financialised at pretty well every level. The titles of British TV programmes such as Fake or Fortune?, Cash in the Attic and Flog It! attest to the extent that material culture has become perceived as a cash prize, rather than something to live with and enjoy, à la Vogel.

As a result, most antiques have never been cheaper, at least at auction. “There are wonderful opportunities in this sector,” says Kerry Shrives, the senior vice president at Boston, Massachusetts, auctioneers Skinner, which on 13 July held a 530-lot sale of European furniture and decorative arts. A Spanish walnut chest from around 1700 at $461, and a 19th-century Biedermeier mahogany veneer bureau at $185 were among the handsome period pieces selling way below estimates at Ikea-like prices.

But to what extent do such purchases represent opportunities in a culture that seems to care less and less about old things, or even things? Shrives is aware of recent consumer research that has shown millennials would rather spend their money on experiences rather than possessions and that an increasing percentage of professionals in their 30s and 40s rent rather than own their homes.

“Prices have softened a bit,” Shrives says. Her clients buy in a different way to how they did in the 1980s: “They’ll buy the conversation piece, but then not feel the need to buy seven others.”

For the investment-minded, contemporary art remains pretty much the only opportunity in town, but today how can a collector with only a few thousand to spend hope to emulate the Vogels? At that price level Gagosian is not going to greet you with open arms, but what about cultivating a reputable smaller gallery that is trying to discover and support future Donald Judds and Tschabalala Selfs?

Will Jarvis of the Sunday Painter Photo by Ollie Hammick. Courtesy of The Sunday Painter

The south London gallery The Sunday Painter, for instance, represents the New York-based conceptual artist Kate Newby and the British sculptor Emma Hart, who in 2016 won the Max Mara Prize for Women. Its co-founder Will Jarvis says that there are potentially plenty of new buyers “but they need to be introduced to collecting. The industry is opaque”. Jarvis adds that because of the financial pressures smaller galleries face, “you have to gun for established collections. It takes time to bring on younger collectors, and we don’t have much time”. He says editioned pieces are a good entry point for new collectors.

Newby, a New Zealander, is best-known for her installations but in 2017, while on a residency in San Antonio, Texas, she produced a series of abstract soft-ground etchings made with local fauna. Printed in editions of ten, these are priced at $2,500 each.

These are affordable and can fit into any apartment. But can a print make a decent return on ones money? While editions may not lose value, the chances of a spectacular profit are slim to none.

This, ultimately, is the problematic distinction between the mindset of today’s collectors and that of the Vogels. They did not care about investment; they just wanted to live with the art.