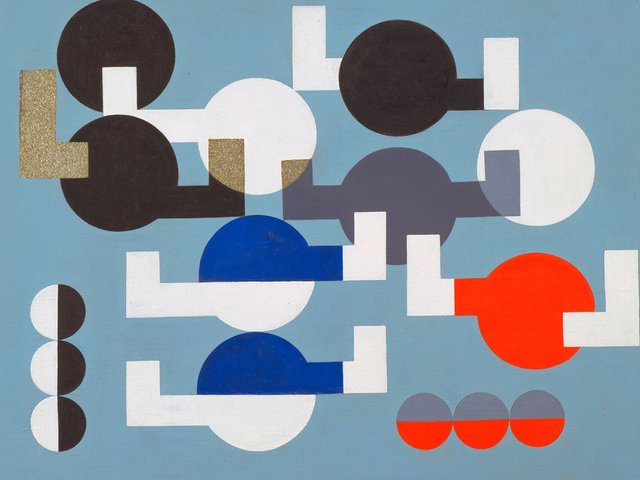

The electromagnetic fields around Tate Modern will be slightly skewed this week for the largest UK exhibition of the experimental Greek artist Takis. With around 70 works from the 1950s to the early 2000s, the show aims to introduce audiences to an artist whose practice—which deals with light, sound and, most notably, magnetic forces—“reinvented what post-war sculpture could be”, says the show’s co-curator Michael Wellen.

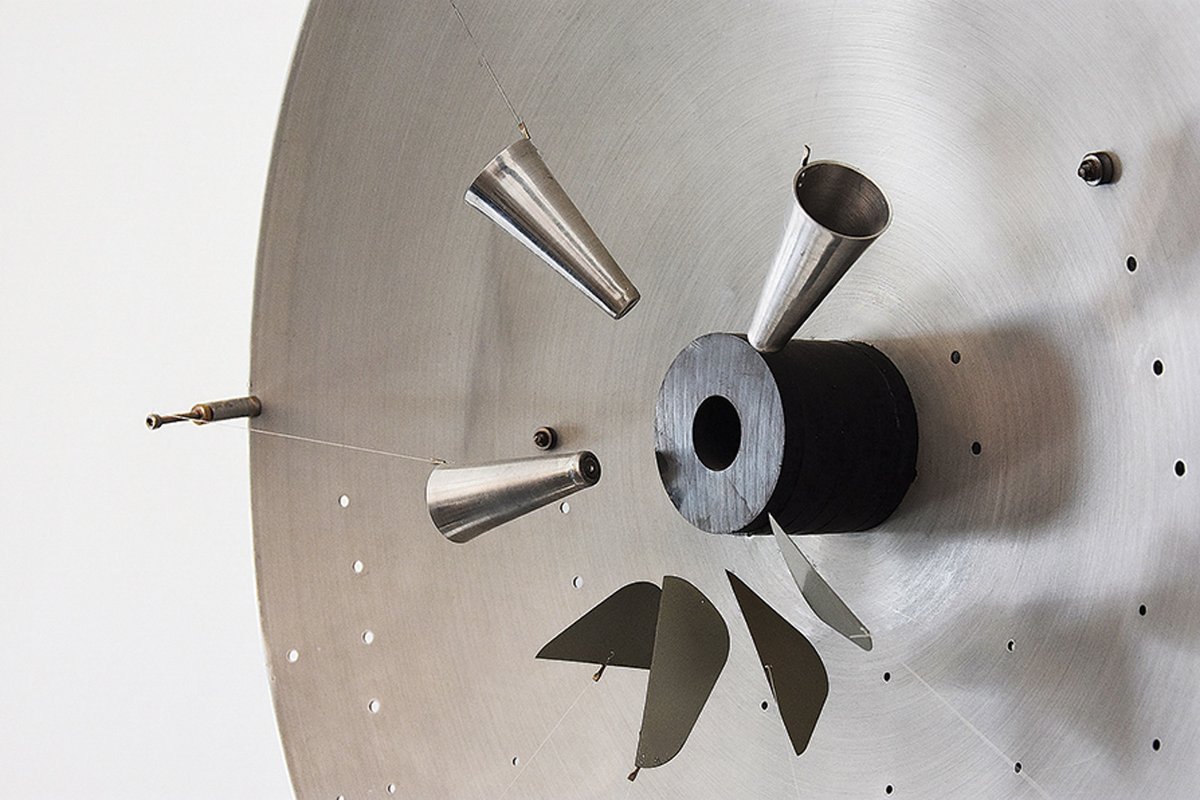

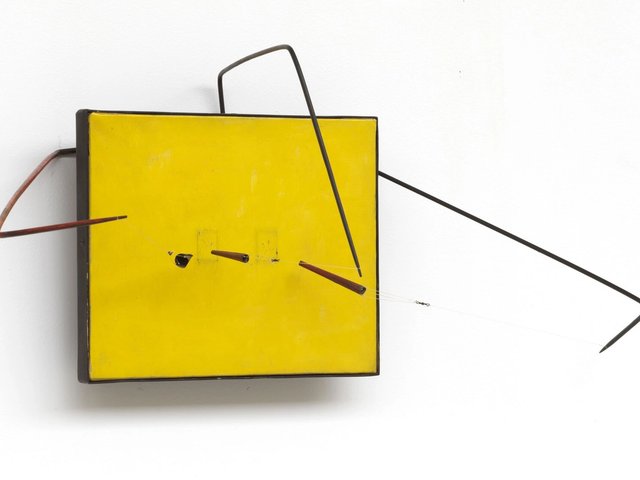

The sculptures mark a departure for the Tate, Wellen says. One includes metal objects floating above a red canvas surface, while another, Magnetic Fields (1969)—which has not been exhibited since the 1970s—consists of a magnetic pendulum operated by museum staff that triggers movement from around 100 rod-like metal structures.

Takis's Magnetic Fields (1969) Photo: Hlias Nak, © ADAGP, Paris and DACS

Alongside the magnetic works, the exhibition will also group Takis’s works under the themes of light and sound. A series known as Musicals will fill the galleries with discordant sound fields from needles randomly striking strings, while the freestanding Télélumière No. 4 (1963-64) will emit an erratic blue light—the result of tinkering with an alternating electrical current and mercury lamp.

The boundaries between what constitutes art and scientific experiments have always been challenged by Takis, says Wellen, who views him as a successor to Marcel Duchamp—who was in turn an admirer of the younger artist’s work. However, it is not just Takis’s use of experimental mediums that continues to keep his work relevant. His long-standing consideration of the effect of rapidly changing technology paved the way for contemporary artists working with the environment, such as Olafur Eliasson, who is the subject of a concurrent exhibition at the museum called In Real Life (11 July-5 January 2020).

The show is supported by Tate International Council and is organised with the Macba Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona, where it opens on 21 November, and the Museum of Cycladic Art, Athens, where it will travel to in May 2020.

• Takis, Tate Modern, London, 3 July-27 October