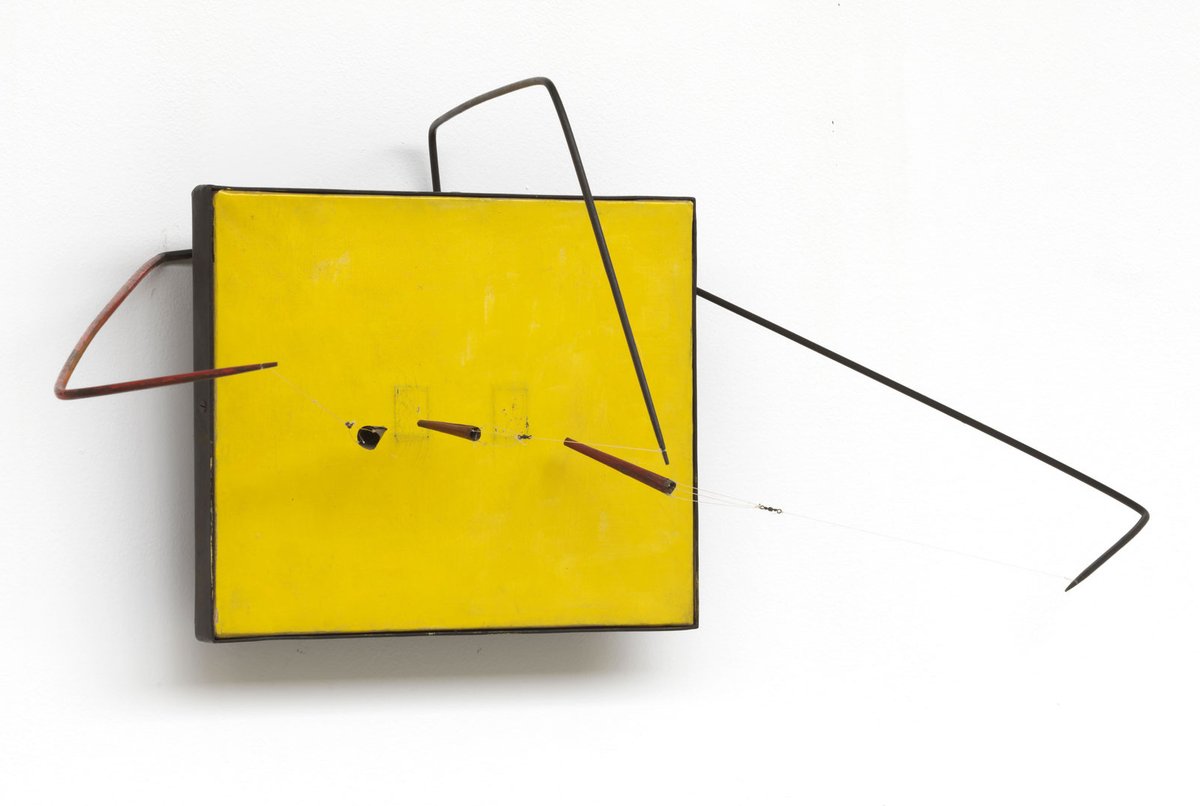

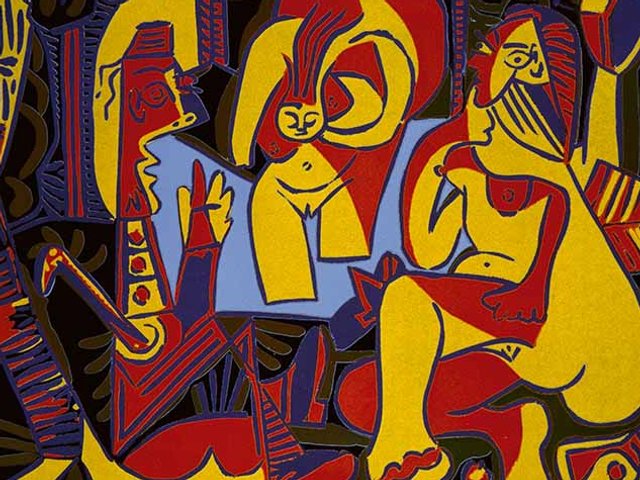

Marcel Duchamp once described the Greek artist Takis as the “happy ploughman of the magnetic fields”—a suitable description of an artist who seemingly ploughed his own furrow in the art world and whose work can also bring unalloyed joy. A thematically arranged exhibition at Tate Modern, which opened this week (until 27 October; tickets £13, concessions available), brings together key works in a show full of wonder which takes you back to that moment as a child when you first encounter the invisible attraction of magnets. Takis began working with magnetism in the late 1950s and in sculptures such as Telesculpture (1959), he seems to freeze time as suspended black spheres and cones are pulled towards the magnet but never quite touch, like a photographed explosion. In his Magnetic Walls series from the early 1960s, abstract shapes seem to have turned into three-dimensional objects and leapt out from the canvas, as though a Joan Miró painting suddenly came alive. Showcasing sculptures using electricity and light, the exhibition is soundtracked by intermittent gongs that draw you to the final room. Here, two sound works, Gong (1978)—inspired by Zen Buddhism and made from an old oil tank— and Musical Sphere (1985) are activated every 15 minutes by a gallery assistant, producing a delightful cacophony that pulls you in.

Three shows opening this week at the Imperial War Museum London, as part of its Culture Under Attack season, highlight both the best and worst of humanity: from the destruction of cultural heritage and even the murder of those who stand in their way, to the extraordinary lengths people will go to safeguard, preserve and recreate important artefacts. What Remains (all three shows are on until 5 January 2020; free), looks at the destruction and then rebuilding or recreation of culturally significant objects, from the new Coventry Cathedral to a 3D-printed replica of an Assyrian lion sculpture destroyed by Isis in Mosul. Art in Exile explores the curious priority grading system used by the museum to select works to send out of London during the Blitz—yes to all works by John Singer Sargent and the less remarkable John Lavery; no to all the works by female artists. It also tells the stories behind the evacuations of works in other major London museums, such as the National Gallery and the British Museum. Finally, in Rebel Sounds, the sounds and stories of people who have used music as an act of resistance, whether in 1930s Nazi Germany, Northern Ireland in the 1970s or present day Mali, are told and played.

Featuring an array of works ranging from Sam McKinniss’s portrait of Buffy the Vampire Slayer shadowed by a toothy attacker to a plush swan penetrating a howling hyena in bloomers by Marianna Simnett, My Head is a Haunted House at Sadie Coles HQ (until 10 August; free) is, like its pop culture horror genre inspiration, a cheap but satisfying thrill that sticks in your brain for far too long. While many galleries go for feel-good summer shows, this one—along with a similar but more macabre companion show at Rodeo, Dracula’s Wedding, both curated by Charlie Fox—probes the psychological depths of memory, general bodily weirdness, and the line between humour and horror proving that even if our parents told us monsters are in our minds, it does not make them feel less real. That does not mean we cannot find solace in the spooky, though.