It would be easy to read the monstrous sculpture positioned near the entrance of Frieze Los Angeles as an allegory about the swampy excesses of the art market. But Max Hooper Schneider, the artist who made this part- walrus, part-woman creature as a Frieze Projects commission, says it is a component of a larger series he is developing. Much of his work uses biological imagery, or actual living organisms, to imagine a world where man has been displaced from his throne. Last December, the Los Angeles gallery Jenny’s featured four of his living tableaux, where tiny fish swam among mountains of cheap plastic jewellery and crustaceans made a home out of mounds of lingerie. Expect an even more immersive experience at the Hammer, where he will have his first museum show in September.

The Art Newspaper: What is the thinking behind a walrus-human hybrid?

Max Hooper Schneider: It’s a long running personal fantasy of mine, these marine mammal hominid hybrid creatures, like half-humans, half-dolphins. I’ve always been obsessed with actual marine mammals—manatees, seals, dolphins—and I imagine scenarios where they could come to land and be equal participants in our civilisations.

And is this creature realistic?

The walrus skull is. I actually went to an anatomical replica company in Palm Desert and they let me cast a walrus skull, although it’s oversized compared to the female figure.

Max Hooper Schneider © Photo: Nick DeLieto

What if people see it as trafficking in women’s body parts?

I’d say I have a pretty democratic approach to human-nonhuman materials, giving them equal agency. Other examples in the series include men, kids and genderless people. It’s my army of marine-mammal people, across all genders.

And how do coral reefs figure in your work?

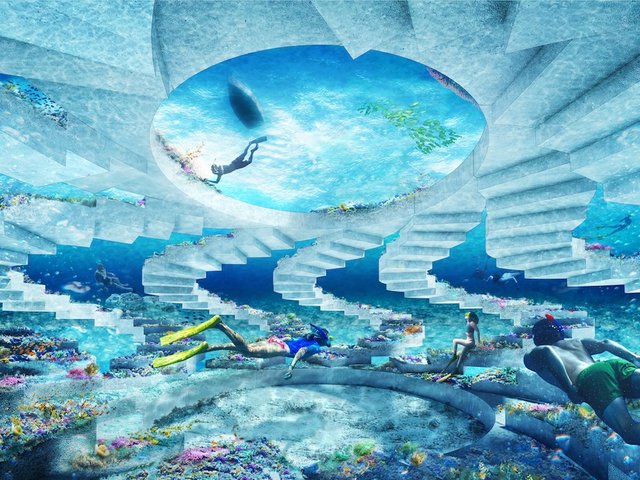

In 2016, I won the BMW Art Journey, where they invite artists to concoct some sort of wild journey. Mine was my bucket list of ultra- ultra-remote coral reef sites all over the world: eight different ones, each with its own typology, in various states of flourishing and decay. I started in New Zealand on an active volcanic island that is home to extremophiles: organisms that can live in typically lethal conditions, like the bacteria that lives in your salt shaker. I was interested in reefs because coral is the first responder to global and environmental change— they are the first to tell us if sea temperature is rising, or if water chemistry has changed. So I could use that as a lens for approaching humankind’s present moment on the planet. It furnished me with a poetry for thinking about what’s next, not just dystopia or apocalypse.

You consider some of the works in your last gallery show “reefs” of a sort.

Two are “reefs” in quotation marks. One was a whole architecture of lingerie and seductive wear. In most instances, the polyurethane and synthetic fabrics would be lethal to a marine habitat, but I had cultivated and cured it until it got to the threshold where it could become a fertile substrate for marine organisms. I chose to use mainly invertebrates—decorator crabs and starfish and snails—because I understood their behaviour. I also tend to use organisms that are very hardy, the kinds that will, in my imagination, inherit the world when we’re gone.

Many kids dream of being marine biologists but this was a real ambition for you.

I’ve always had an obsession with marine biology. I grew up near the Pacific Ocean doing tide pooling, and I had a menagerie of aquariums since I was seven or eight. But by the time I was heavily into it, studying marine biology and biology at NYU and working in labs, I grew disenchanted by how data is produced. In many ways I want to keep things mysterious; the modes of empirically knowing something are less interesting to me. My mother is a scholar of [the 17th-century philosopher] Spinoza, and she furnished me with a certain type of thinking that loosened empirical strictures of sciences.

Max Hooper Schneider's Pet Semiosis 15 (2018) © Michael Underwood

How did you start working for Pierre Huyghe?

In my last year of grad school [at Harvard] in 2011 [where I did an MA in landscape architecture], I saw Pierre’s aquariums at Marian Goodman and was enraptured. And fortuitously, when I moved back to New York, they advertised for someone with an understanding of aquariums, marine biology and also contemporary art. I walked in and they said there’s no other candidate. Pierre and I had this weird nerd rapport with a macabre sense of humour—he was into cheesy splatter films and collected fossils. I freelanced for him for almost three years as an install technician, helping to manage all the aquariums, setting up the biology, water parameters and maintenance.

Some might say your work is the Malibu version of Huyghe. What makes it different?

I think I introduce a heavier handed narrative. I tell stories. For instance, with the lingerie reef, I’m really telling a story about some Big Bang-like moment, some flash underwater that petrified human garments. I sometimes think of the sculptures as short stories. Pierre’s stuff is so much more open-ended; he sets up the rules for the game, but he won’t tell you what the game is.

When I first met you, you were wearing a death metal T-shirt. Is that what you listen to when you work?

Yes, 24/7. I wake up an hour early every morning just to download new albums: pure death metal or heavy metal. It’s 100% an obsession. I think there are superficial reasons for it but also brain chemistry or physiological reasons. Sonically it calms me down. The more abrasive, the more guttural, the better for me. It’s like giving speed to someone with ADD. I think this kind of music concentrates the chaos of the world into a small space, like putting it into a Tupperware container, and then I can relax and focus on minutiae. I can do surgery to it. The only thing I can’t do during it is write academically.

Tell us about your Hammer Projects show.

I’m doing a human-scale dioramic landscape that addresses issues of climate change, especially desertification—when giant bodies of water dry up. The sculptures themselves won’t move but there will be some sort of atmospheric movements or vibrations. I’m also doing the Istanbul Biennial [14 September-10 November], creating a garden of “telegraph plants”, whose leaves are visibly active, constantly moving towards light. Part of my practice is demonstrating the agency of the world out there—a decentralised, non- solipsistic, non-anthropocentric approach.

• Hammer Projects: Max Hooper Schneider, Hammer Museum, (22 September-5 January 2020)