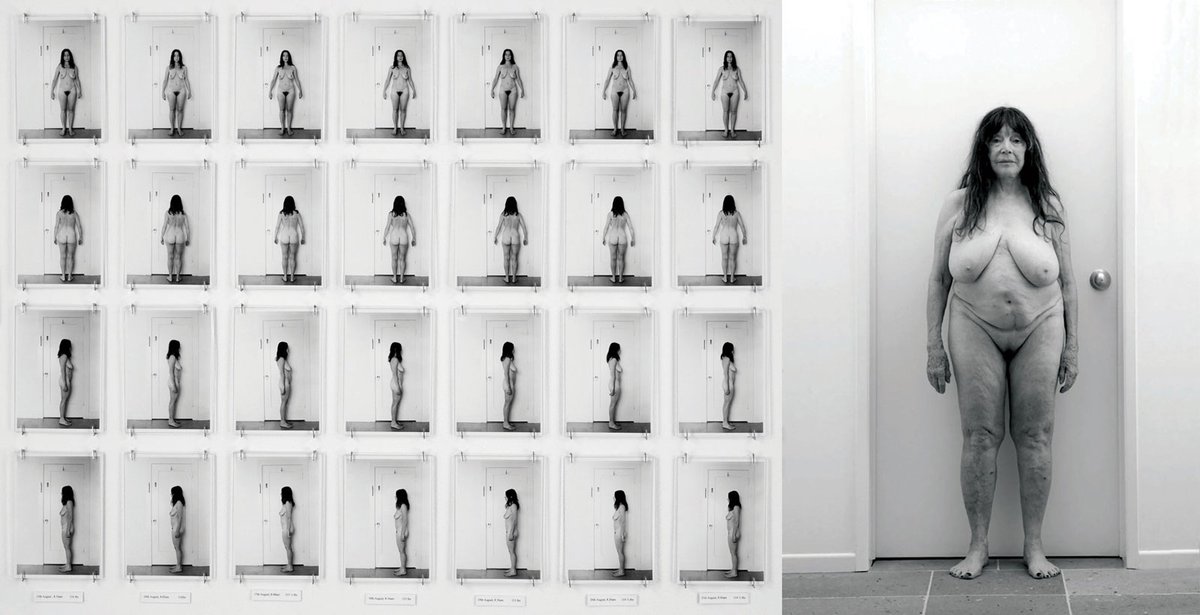

When Eleanor Antin made the landmark feminist work Carving: A Traditional Sculpture in 1972—photographing herself naked every morning during a few weeks of hardcore dieting, at age 37—she was testing her physical stamina and vulnerability. But it takes another kind of bravery to revisit the project at age 82, which Antin has recently done. The project will make its debut alongside the original next May at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (Lacma) in a focused show called Time’s Arrow. The show later travels to the Art Institute of Chicago, which owns the original Carving series.

Both projects consist of small photographs hung in a grid to track the effects of dieting on her body, which Antin has wryly compared to Michelangelo’s process of carving a sculpture to release the material’s ideal form. The 1972 work has four rows of 37 images, each row of a different angle. Carving: 45 Years Later is even larger, with five rows of over 100 images each. In both, the female form seems to strain against the rigid framework—the flesh resists the grid.

This time around, the fat was more stubborn, which led to a longer dieting time and larger format. Antin explained in a project statement that she “was too vain to start at 141 pounds. So I began [dieting] without photographing myself. It was amazing. I lost 11 pounds so quickly and easily.” But when she started to document her weight loss, the pounds proved harder to shift, creating a more sceptical meditation on our ability to shape our bodies and lives.

“Everything Eleanor does has a deep humour to it, but I find this work has more gravitas,” says Lacma’s director Michael Govan. “She’s presenting herself very bluntly and directly, raising questions about aging and mortality.”

Antin started the work shortly after her husband, the poet David Antin, died from Parkinson’s complications. “I think I chose to redo this piece at this time because it’s basically about loss. The loss of my flesh, the loss of my lover and partner of 56 years, the loss of the body I used to know and lived with for so long (though like so many women, I was often trying to change it because it was never quite right),” she writes in an email.

True to form, she ends on a lighter note: “And hey, though this piece is a confession of imperfection, it still presents hundreds of photos of my naked, imperfect self. There’s a profound egotism here as well.”