On arriving at the Bauhaus as a student in 1922, Anni Albers (then Anni Fleischmann) was dissuaded by the school’s founder, Walter Gropius, from working on “heavy craft areas”, which included painting, her preferred medium. Directed towards the more “feminine” weaving department, Albers took to it with a gusto that changed the face of what the medium could be and in the process became one the 20th century’s most important textile artists (it is principally because of her that such a term even exists). Albers’s experimentation with materials and patterns and the way she pushed the boundaries of what constitutes fine art, is explored in the first major retrospective of her work in the UK. Tate Modern’s Anni Albers (until 27 January 2019) exhibition, which opened this week, includes more that 350 objects spanning her career, from large wall hangings made while she was still at the Bauhaus to later silkscreens and lithographs from the 1970s.

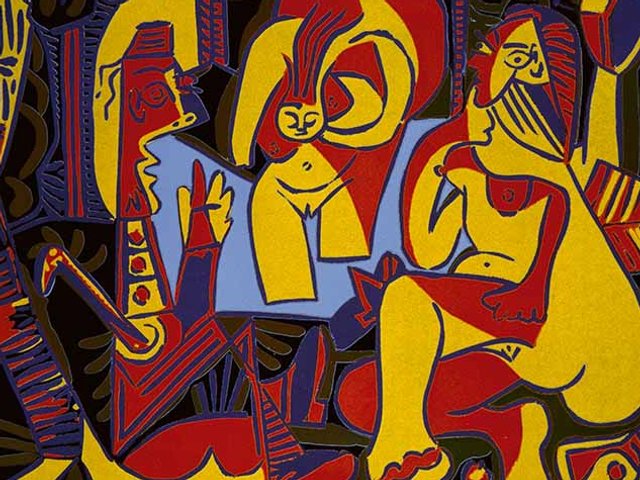

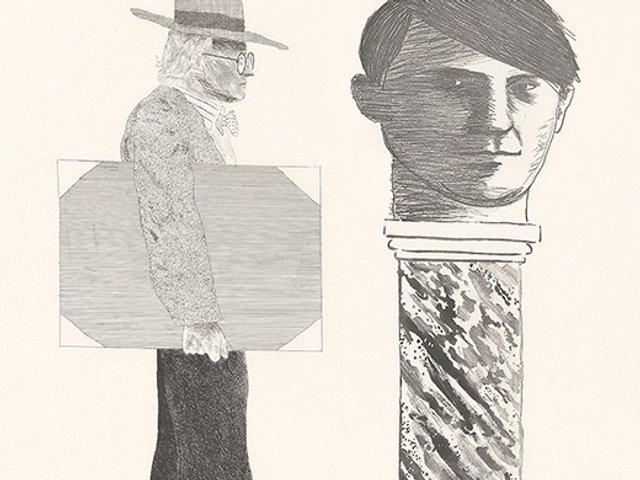

It could be argued that Anni Albers now eclipses her husband Josef, as the better-known artist in that couple. Their relationship is one of the few from the early 20th century that is not covered in an extensive exhibition at the Barbican Art Gallery on artist couples. With more than 40 relationships under the microscope—including conventional marriages, fleeting romances, platonic friendships and everything in between—Modern Couples: Art, Intimacy and the Avant-garde (until 27 January 2019) looks at how artists who were intimate also influenced each other. With a handful of works for each and supporting documents, visitors get a snapshot of relationships such as those of Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera, Lee Miller and Man Ray, Pablo Picasso and Dora Maar, Alexander Rodchenko and Varvara Stepanova. Among the highlights are an unusual near-abstract Salvador Dalí painting, Female Nude Seated in an Armchair (1927-28); Georgia O’Keeffe’s luminous Red, Yellow and Black Streak (1924); and Sonia Delaunay’s bold and colourful fabric designs painted with gouache on tracing paper.

The paintings and drawings of two giants of the early Italian Renaissance—Andrea Mantegna and Giovanni Bellini—have gone on display side by side at the National Gallery in an exhibition that aims to demonstrate that the two artists had a profound and lasting influence on one another. Mantegna and Bellini is the first show ever to examine the artistic dialogue between Mantegna, the self-made son of a carpenter from Padua, and Bellini, who hailed from a hugely successful artistic dynasty in Venice and would come to be recognised as one of the city’s greatest painters. “They excelled at different things,” says Caroline Campbell, one of the exhibition’s curators. “Mantegna revived the art of classical antiquity and made astonishing narrative paintings that made history seem alive; technically, he was a master of foreshortening. Bellini was a master of light, colour and landscape—nobody painted those as skilfully as he could.”