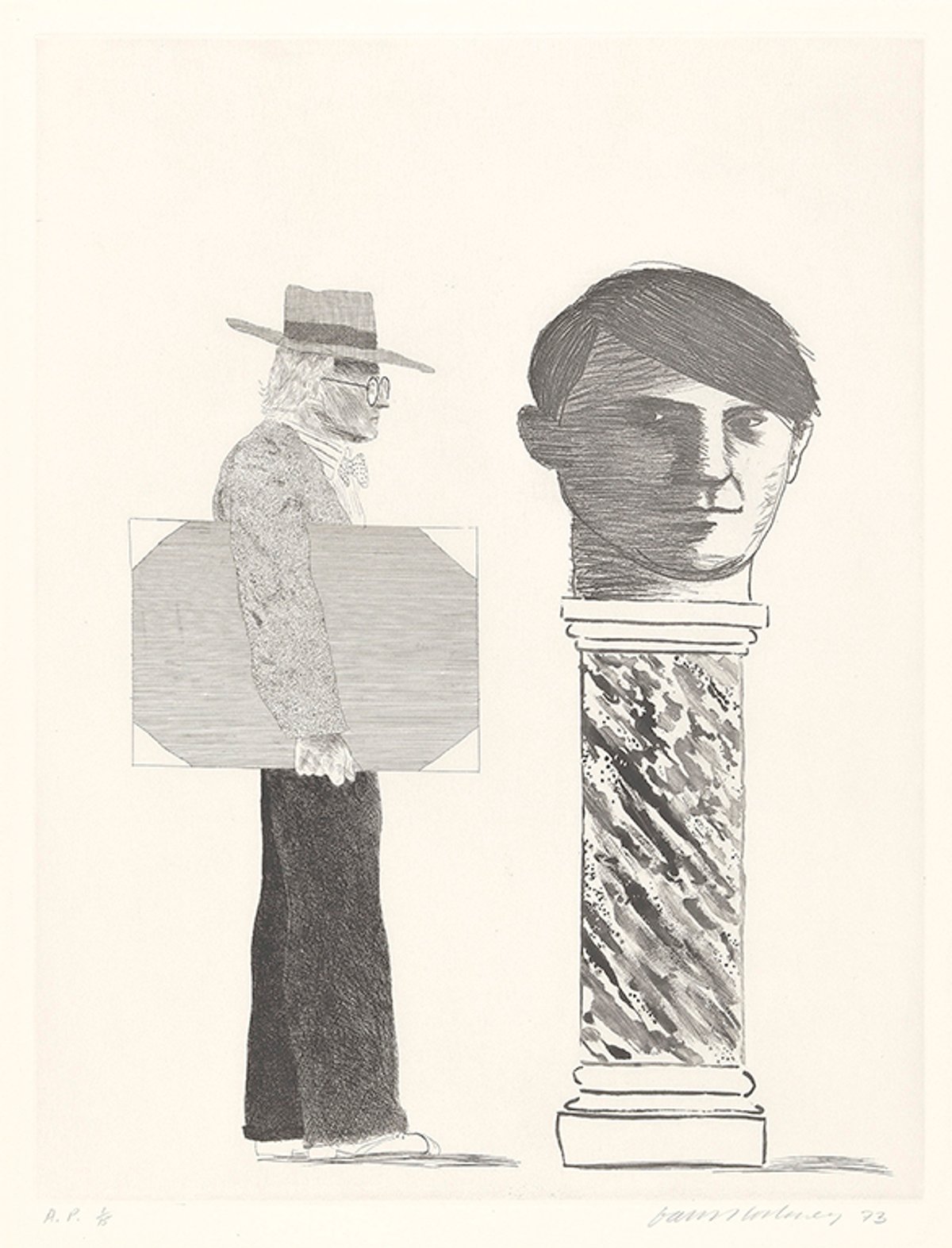

It is fortunate that David Hockney, at his best, is a great artist. Despite a sometimes confusing layout and some dud rooms in David Hockney: Drawing from Life (until 28 June; tickets £20, concessions available) at the National Portrait Gallery, the quality of his work—especially early etchings while a student— makes it worth seeing. Nominally, this is a show of Hockney self-portraits and depictions of those close to him, organised thematically and, kind of, chronologically (at one point his subjects are referred to by their first names on wall texts before we have been properly introduced to them). However, there are still some stunning pieces in the show, reminding us why Hockney is rightly regarded as one of the UK’s greatest contemporary artists. Works dedicated to his two most important female muses, Celia Birtwell and his mother Laura Hockney, demonstrate his intricate drawing skills, such as the coloured pencil Celia, Carenac, August 1971. His innovative work in the 1980s also saw him create intimate photographic collages. Most strikingly, My Mother, Bolton Abbey, Yorkshire, Nov. 1982 is bathed in pathos, showing his widowed mother wrapped up in a green raincoat sitting on a tombstone. Hockney’s etchings made in the early 1960s, when he was still a student at the Royal College of Art (RCA), show a self-deprecation and reverence for his heroes but also a sense of confidence in his willingness to place himself alongside them. A Rake’s Progress, his homage to Hogarth— an intricate and playful mix of styles and perspective, with witty uses of language—is a joy. It is all the more impressive as Hockney only began etching because the printmaking facilities at the RCA were free and he had run out of money to buy painting materials.

It's your last chance to see Young Bomberg and the Old Masters at the National Gallery (until 1 March 2020; free), a show which effectively flips the script on our popular understandings of Bomberg's relationship to Western art history. Instead of severing ties from Rembrandt and Michelangelo, Bomberg's audacious brand of modernism was, it turns out, heavily—and avowedly—indebted to the past. Confined to just one room, the exhibition is pressed for space, showing just 8 Bombergs (half of which are preliminary studies) with two Old Masters. Botticelli’s Portrait of a Young Man (around 1480-5) hangs besides a pencil self-portrait, directly influenced by the quattrocento painting, with both men possessing similarly charismatic, determined stares. Even better is the painted study Sappers at Work (1918-19), a towering portrayal of a mine attack in World War I, which has its striking roses and lilacs tied to the swirling pinks and purples of El Greco. Mercifully, Bomberg is never pitted against these Renaissance heavyweights (there is no doubt who would win). Instead, the show allows for his clear reverence of the Old Masters to remain the focus, serving to both reposition and elevate his artistry.

The sweeping photography show Masculinities: Liberation through Photography (until 17 May; tickets £15-17, concessions available) shines a light on the fluid and plural nature of what it means to be a man. Although it includes images by some of art’s most famous practitioners: Robert Mapplethorpe’s images of a then little-known bodybuilder called Arnold Schwarzenegger join masculine-centric images by Andy Warhol, Wolfgang Tillmans and Catherine Opie, the most interesting works come from lesser-known names. Offerings by Thomas Dworzak show a trove of self-portraits by Taliban soldiers, who, despite being forbidden to be photographed, were allowed to take passport pictures. Taking advantage of this liberty, they used the privacy of the photo booth to create remarkably ambivalent variations on the kind of masculinity being imposed on them, posing hand-in-hand in front of idyllic painted backdrops, with flowers in their hair and kohl lining their eyes. The show’s curator Alona Pardo says she “is calling for a total rethink of gender”. The photographs here expose masculinity as a malleable and fluid construct—one that morphs and changes across era, generation and culture and is often learnt through practice, communicated via performance and amplified through popular culture. By presenting masculinity as eluding one simple definition through endless subtle variations Pardo says, "the show acts a counter-balance to the established order of things."