A decade ago, one began to witness the rise in popularity of a vegetable that had always been with us: kale. One could hardly go to a trendy restaurant or grocery store without noticing its ascendancy. Off the menu or to the side of the shelf went spinach, savoy cabbage and other old standbys. It was now kale for anyone aspiring to youth, health and coolness. However, aside from excellent marketing and product placement, there was little reason for kale’s phenomenally growing appeal.

Over the same time, a similar development has taken place with contemporary art. Its unstoppable rise has pushed all other art to the side, mirroring a trend that began in the art market, then took place in the art press, and finally happened in museums and academia as well. This radical shift in the art world has been advanced by clever marketing orchestrated by the greatest forces in the market and is eviscerating the presentation and understanding of our artistic heritage.

How this came about is a story worth telling, since it is the first time that the market has almost entirely dictated artistic taste in museums. Through the 1950s, Old Master art dominated the market. By the following decade, it became clear that the supply of top material was dwindling while being increasingly encumbered by issues of export and patrimony. To the rescue came French Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, as well as the early phases of Modern art. The supply seemed vast, the subject matter more appealing and less challenging, and the visual appeal immediate. Until the end of the 20th century, it remained the period of choice for the biggest new collectors. By contrast, museums played a dominant role in the field of Old Masters. It was the era in which the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC bought Leonardo’s Ginevra de’ Benci and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York Velázquez’s Juan de Pareja.

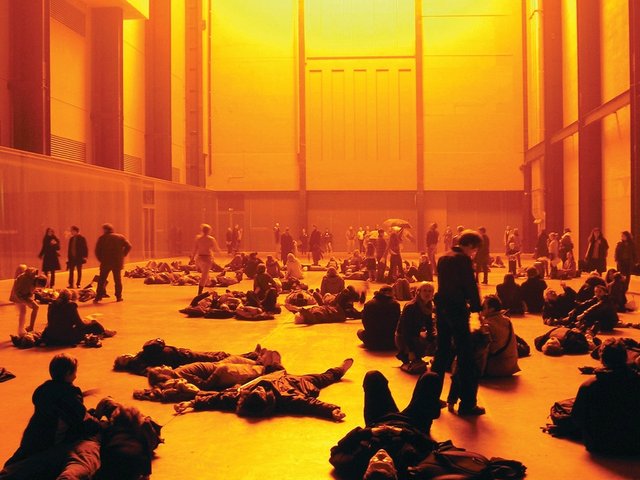

By the 1980s, the game had changed. The top tier of collectors became much richer and museums gradually lost the ability to compete with them. Globally, the number of the very rich grew exponentially. By the turn of the century, there wasn’t enough important art to satisfy this increased demand and the art market suffered. Thus began a relentless auction house and dealer campaign to promote the only field in which supply was limitless: contemporary art. Contemporary art was for the young and new rich, the cool generation. It required little cultural background, entirely suitable for the plutocrat who had never studied the humanities. Connoisseurship became irrelevant, as, for the first time, close similitude with other works by an artist became a virtue and a selling point.

The press eagerly jumped on board. New artists, new stories, new leaps in value: all very newsworthy. And more advertising revenue, as well. Can there be a better example of the collusion of the press and the market in the sale of a painting than the Salvator Mundi, possibly by Leonardo, in a contemporary art auction?

Next in line came the museums and academia. Museums began to worry about their relevance to a society in which the study of humanities was in sharp decline. They also began to worry about where large donations would come from if the major, very rich collectors were buying contemporary art and they were not active in that field. And, as these new rich collectors began to appear on the boards of museums, they assiduously began to promote their own field, ignoring the underlying conflicts of interest that this presented. In turn, museums began to disproportionately favour candidates for directorships who came from that field or promised to advance it.

Academia followed suit. More jobs were available in contemporary art, young people were told it was the cool place to be, and so it began to be taught in disproportion to its place in the history of art. And it was the perfect field for a generation that has little appetite for the hard work needed to master the traditional humanities, as well as their professors who loathed connoisseurship.

Most recently, museums and academia have added a further note to justify their direction. Contemporary art has somehow become associated with diversity and social justice, whereas older art has become emblematic of the evil, entrenched establishments of the past. The falseness of this connection is obvious, since the art of today serves and reflects the power structure of society, just as it has always done.

In fact, if one truly wishes to understand many diverse cultures, the place to start is with their respective histories, not the contemporary art of an ever more homogenous world. And, if museums want to do more for diversity, they might well start by diversifying their boards and hiring directors of different backgrounds. Then, one might hope that they would not all repeat the same ideas in the same way, as if reading from the same script, and that some new ideas would emerge. However, the very first step in advancing diversity of audience for most US and some Continental European museums should be to make sure that the poor can enter at no cost, following the excellent example of the UK’s national museums.

This brings us back to the beginning of our story, to kale. It is no better-

tasting and no healthier than many other vegetables. It is but one vegetable. The same is true of contemporary art. The public has shown, through its attendance at major shows of older art, that it wants a range of options. So it is time for museums to return to their true mission: the presentation and teaching of art from all significant periods and cultures, oblivious to temporary market trends and distortions.

• George Goldner was formerly the curator of drawings and paintings at the Getty Museum and the chairman of drawings and prints at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York