The Turbine Hall at Tate Modern is perhaps the most well known, and probably the most photographed, space in the world of contemporary art. A striking feature of a great example of 20th-century industrial architecture, it has hosted the important Unilever (and now Hyundai) series of large-scale installations since the museum opened at the Millennium. But as you enter Tate Modern what you initially experience is not so much particular artworks as an impressive space. In the public imagination, what Tate Modern first presents is the dramatic setting for a contemporary art experience.

In 1990, the art historian Rosalind Krauss described this situation as characteristic of the late capitalist museum. Reflecting on an exhibition of the Panza Collection of Minimalist sculpture, she noted that the object of her perception did not seem so much to be the art itself, but to be the museum as a building. In an age of “starchitecture” this might not be surprising, but her analysis had more to do with the developing character of museums than with their architectural notoriety. For what Krauss observed was a departure from the traditional museum’s intention of providing an art-historical narrative. Rather, what she saw museums now seeking to deliver was a certain kind of spatial engagement. And to produce that experience spaces of great size were needed, such as those planned by Guggenheim Museum director Thomas Krens for MASS MoCA, which opened in western Massachusetts the year before Tate Modern.

An end to chronology The years around the Millennium offered not only large-scale spaces for contemporary art, but, as Krauss foresaw, departures from the chronological narratives that had begun structuring major collection displays in the late 18th century. For one of the most striking features of the newly opened Tate Modern was the decision to present the collection thematically rather than historically, using broad topics such as “Landscape/Matter/Environment”, “Nude/Action/Body” and “History/Memory/Society” to configure the displays. Across the Atlantic, the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) had also embraced a thematic approach when rehanging the collection in late 1999. Before closing its building for a major expansion, the museum presented its collection around the pedestrian themes of “People”, “Places” and “Things”. It was a radical divergence, albeit temporary, from the rigid chronology of MoMA’s canonical narrative.

The thematic presentation at Tate Modern in part was governed by the nature of its collection, which did not have the depth to support a rich chronological survey of the development of Modern art. But the justification for such ahistorical displays also involved a more Post-Modern attitude that rejects the demand for a single analysis of culture. Rather than an unique, linear path through history, it is claimed that there are many paths, and many ways, in which the same collection can be configured so as to yield an illuminating view of artistic production. Here, there is not one truth but many truths, not one story but many stories, each able to represent the past, and its relation to the present, from a coherent standpoint. At Tate Modern traditional art-historical chronologies co-exist with thematic displays, most visibly in timeline murals outside the entrances to the collection galleries.

The move away from chronological presentation was also motivated by social and political considerations of access and diversity. From a populist viewpoint, a broad and varied audience responds more favourably to engaging narratives than to textbook art history. This audience-focused stance has been embraced in both the US and the UK by museums that seek to attract larger, more inclusive groups of visitors. Such a public, it is thought, finds viewing chronological exhibitions to be too much like schoolwork, which is something to be avoided as museums compete for leisure time with other forms of popular amusement. Critics have charged that a move from historical to thematic presentations is a retreat from the museum’s educational mission in the direction of infotainment. For its advocates, however, the departure from chronology is a way of expanding the effectiveness and reach of the museum-as-educator.

Mini-Bilbao Effect Museums, of course, are concerned with much more than education, and the role of Tate Modern in attracting international tourists and local audiences has been central to its success. The museum website notes that it is one of the top three tourist destinations in the UK, and that each year the museum contributes about £100m to the London economy. Yet the museum’s economic impact has not been a matter only of increased tourism and rising attendance, which has reached five million visitors a year—it has also involved the kind of urban development touted enthusiastically by the cultural sector in the 1990s. Generating its own mini-Bilbao Effect, Tate Modern has been critical to the enhancement of its Bankside neighbourhood, a process of increasing property value and spreading the kind of lifestyle amenities seen worldwide in cultural development zones.

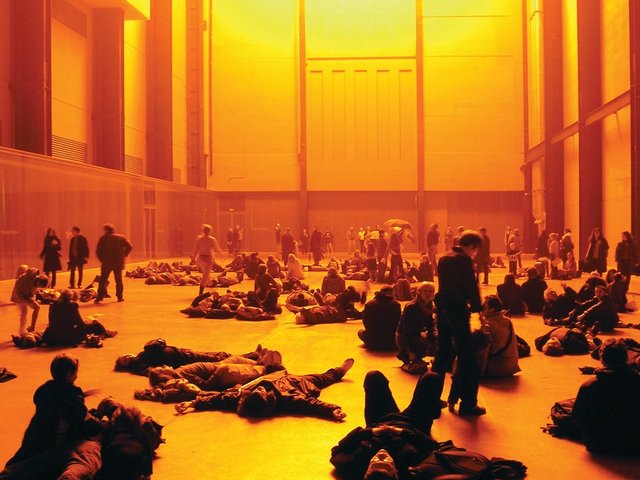

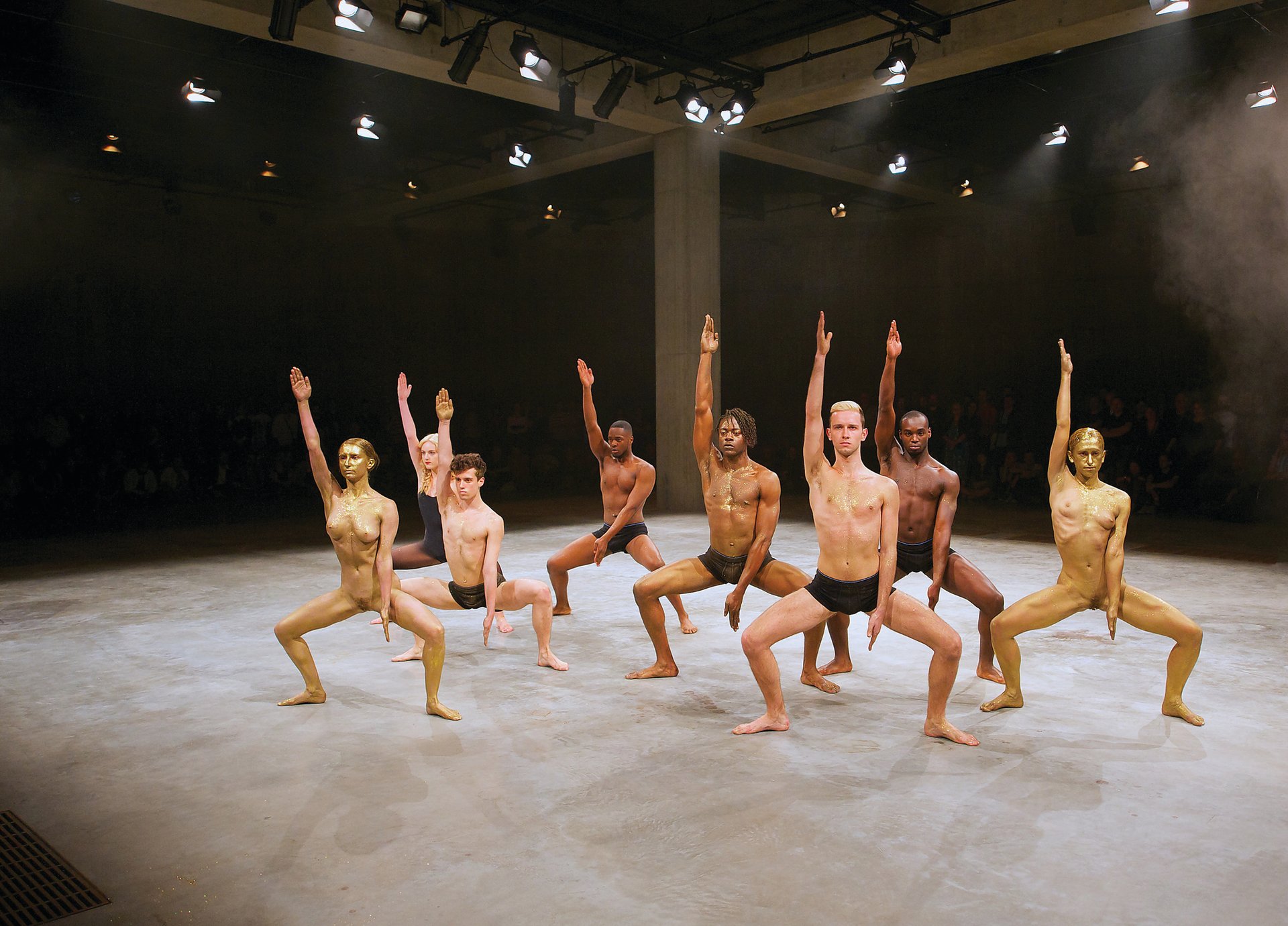

A primary instrument of Tate Modern’s magnetism is spectacle, from its massive presence along the River Thames into the Turbine Hall installations, where the towering interior was employed most dramatically in Olafur Eliasson’s The Weather Project (October 2003-March 2004). More recently, the opening of The Tanks in 2012 has provided a dedicated setting for performance, a variety of public spectacle that has become essential to contemporary museum programming. This is a worldwide phenomenon, with museum renovations, expansions and new buildings increasingly incorporating performance spaces. And the very enterprise of presenting exhibitions of contemporary art has assumed a spectacular dimension, given the confluence of art, fashion and pop entertainment. Emblematic of this is the media attention that developed around the Turner Prize competition and award ceremony.

The embrace of performance also reflects two important influences on the contemporary museum. One of these is the notion of a museum as a site of public gathering, a locus of multiple activities attracting a diverse public: film screenings, dance and theatrical performances, lectures, restaurants and bars, places just to hang out. The other is what has been called “New Institutionalism”, a set of experimental practices originating within international biennials of the 1990s. From this perspective, museums were not to be viewed only as places of display, but were to function as multidisciplinary sites of artistic production and inquiry. In this vein Tate Modern has produced a wide range of performative and participatory projects alongside its many exhibitions, such as Tate Scavengers’ one-day London-wide clue-following (2005) and Tania Bruguera’s Immigrant Movement International (2012). And across all of Tate’s museums, but especially at Tate Modern, a range of research projects have spanned education, art history, literature, ethnography and art conservation to generate discussion among specialists, public conferences and publications. Since 2004, the museum’s Tate Papers has been the most ambitious of contemporary museum journals.

The newest of Tate’s six research centres is focused on the Modern and contemporary art of Asia, and since its earliest years Tate Modern has put significant effort into collecting and exhibiting art from outside Europe and North America. Beginning in 2002 with the creation of the Latin American Acquisitions Committee and the three-year appointment of Mexican curator Cuauhtémoc Medina, Tate Modern has expanded its interests and reach through the creation of acquisition committees for the Asia-Pacific region in 2007, the Middle East & North Africa in 2009, Africa in 2011, and in 2012, South Asia and Russia & Eastern Europe (for more, see pp18-19). In creating these committees and supporting their activity, Tate Modern has been an international leader in the reorientation toward the global museum collecting of Modern and contemporary art.

Capital gains Relying on these acquisition committees to fund its collecting of so-called non-Western art, Tate Modern has actively embraced the kind of ambitious fundraising from non-governmental sources that has long supported US museums. And such private funding has been important to Tate Modern’s success from its earliest years. In this it has become a model for museums throughout the world that in the past had relied almost entirely on government funding to support their operations. Unfortunately, few of those institutions can call on the wealth of a financial capital of London’s importance, nor on the resources of a city that has become so enamoured of contemporary art and culture.

This symbiotic relationship with new moneyed elites and their cultural interests marks Tate Modern as very much of our time, embedding it in the web of mega-collectors and mega-galleries that constitutes the popular face of contemporary art. But just as characteristic of the contemporary museum is its openness to non-traditional audiences, a diversity of visitors largely made possible by Tate’s lack of admission fees for other than special exhibitions. Beyond rectifying art-historical exclusions and embracing a more broadly defined art world, the museum’s global collecting and exhibiting feeds, and is fed by, these very different stakeholders. Adding massive attendance, spectacle and scale to the mix, along with collection and archival research updated in an interdisciplinary mode, Tate Modern has become the paradigmatic 21st-century museum.

• Bruce Altshuler is director of the programme in museum studies, New York University