In May, the photographer Edward Burtynsky unveiled the first fruits of his five-year Anthropocene Project at the Photo London art fair, in the form of an augmented reality (AR) installation. Taking the name of our present geological era recently proposed by geologists and climate scientists, the project is multidisciplinary, featuring a film, a Steidl book, Burtynsky’s trademark large-scale photographs and virtual reality (VR)—all of which will be brought together for two exhibitions in Canada opening in September. The project follows the Anthropocene Working Group of geologists, and captures the devastating impact of humankind across the planet. Strikingly, Burtynsky told us that, while the term is gradually being more widely used, “it is the scientific and arts communities that are propagating the term Anthropocene, more than anywhere else”.

That Burtynsky sees the arts at the vanguard of climate change thinking speaks to the power of diverse cultural forms to grapple with complexities and find ways to communicate them. Among the biggest problems facing environmental campaigners—apart from the recklessness of the US, the world’s second largest polluter (according to the World Bank)—is in communicating the intricacies of the science and the need for urgent action. It is not helped by the warped sense of balance applied by media organisations to an issue with overwhelming scientific consensus: in April, the BBC was rebuked by the UK media watchdog Ofcom for not challenging false claims made by the prominent climate change denier Lord Lawson on the radio last year.

In the visual arts, a greater sense of activism is possible, and it’s being helped by the absorption of a broader range of disciplines and media into the canon. New technologies have been used in many of the best works, so it is no accident that Burtynsky is using AR and VR. John Akomfrah’s Purple, shown in London last year and recently in Madrid, used multi-screen video installations to reflect on present climate change theories through both new HD footage and archive materials. The brilliance of Akomfrah’s work lay in its ability to reflect an industrial past together with historic global colonisation and related cultural identities as the hinterland haunting environmental catastrophe. In Purple, one was repeatedly confronted with a figure in a protective white suit, framed by epic landscapes, imbued with beauty and terror. It was a clear reference to Caspar David Friedrich’s image of man enveloped by nature; the Romantic sublime imbued with insidious toxicity.

Akomfrah’s work was informed by the philosopher Timothy Morton, who sees climate change as an example of “hyperobjects”, which he describes as “entities of such vast temporal and spatial dimensions that they defeat traditional ideas about what a thing is in the first place”. The installation powerfully reflected a sense of that vastness. Akomfrah told The Art Newspaper last October that, while he might aim to be explicitly polemical when he starts a project, he ends up in “reflective mode”—he is more like Morton than populist climate change campaigners such as Al Gore. And yet, the emotion within his very human language cut through, so that Purple did not simply pose questions: however poetic and subtly allusive, it certainly fired me up.

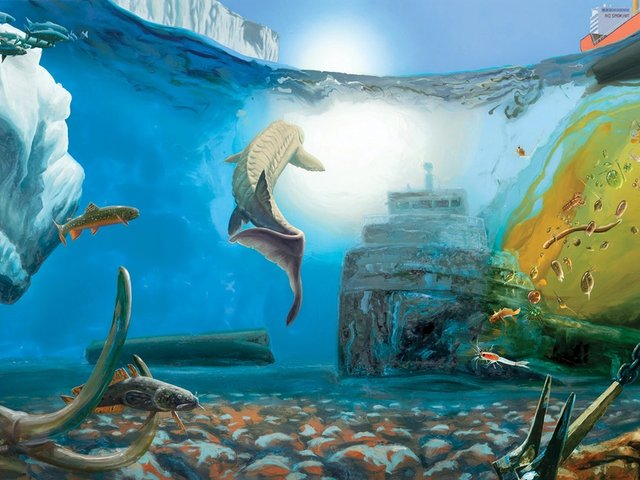

One of the most passionate and articulate advocates for this ability that art has to address the Anthropocene is the US artist Justin Brice Guariglia. He began his career as a documentary photographer in China, capturing the “great acceleration” that is at the heart of theories about this new geological era. But he made the shift into art because he wanted, he told me, “to figure out how could I make something that is more effective, because photography is more about the past. Very little photography is really about the future, whereas great art is really about the future.” To reject reportage, the discipline that is most associated with urgency and action, in favour of the wide-ranging disciplines of art installation, is a bold gesture. But it is an exemplar of artists’ conviction that they can effect change. We may, as the artist Alexis Rockman says, be “fucked”, but artists are not sinking without a fight.