The Dapper Foundation in Paris is stalling requests for dialogue with the Cameroonian claimants of a sacred sculpture that was acquired by a German colonial agent more than 100 years ago, according to a lawyer representing the Bangwa people of Cameroon.

The discussion over African heritage in French museums has gained new urgency after President Emmanuel Macron pledged “a temporary or definitive restitution of African heritage to Africa” over the next five years.

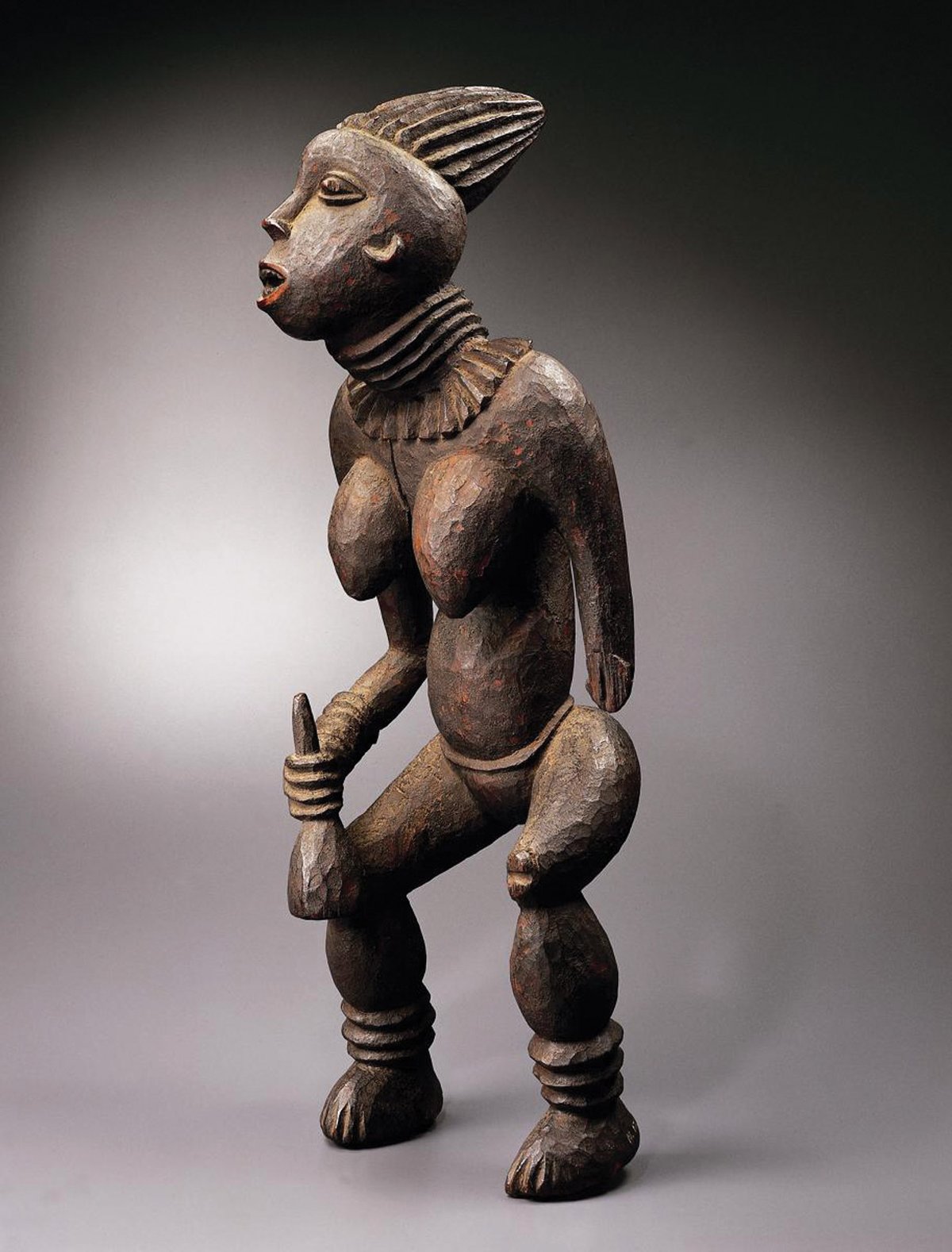

Known as the Bangwa Queen, the sculpture was either given to or looted by the German colonial agent Gustav Conrau, before Germany colonised the Bangwa grasslands region of what is today Cameroon and violently quelled insurrections. The sculpture was subsequently given to the Museum für Völkerkunde in Berlin. It later entered the art market and was purchased by the US collector Harry A. Franklin in 1966. His daughter sold it at auction in 1990, where it was bought by the Dapper Foundation.

Earl Sullivan, a lawyer based in The Hague who is representing the Bangwa king Fon Fontem Asabaton and chief Fuatabong Achaleke, says he has written three times to the foundation requesting information and dialogue about the Bangwa Queen sculpture.

“We have received no substantive response, only requests for verification,” Sullivan says. “As the party with power, resources and access to information, they have not given us the impression that they respect how meaningful these artefacts are to the community, nor that they intend to take us seriously.”

The Bangwa Queen was one of many items removed from the region during the colonial era, but it is one of the most important—alongside the Bangwa King, which is at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, Sullivan says. The female sculpture represents a physical manifestation of the power and health of the Bangwa people and is still considered sacred to them today. “The removal of these artefacts has resulted in a sense of great and ongoing loss for the Bangwa people,” he says.

The sculpture was on display in the privately funded Musée Dapper in Paris, which was established by the Dapper Foundation and which closed in 2017 because of low attendance and high costs. The museum focused on traditional and contemporary African art.

One of the Bangwa people’s main concerns was that the foundation might auction the sculpture, which could then potentially disappear into a private collection, Sullivan says. Christiane Falgayrettes-Leveau, the director of the Dapper Foundation, says the organisation has no plans to sell objects in its collection.

“The Bangwa sculpture, like other works in the collection, will be part of international exhibitions,” she says. “The closure of the Paris building does not signal an end to the Dapper Foundation’s activities. In line with our mission for the past 30 years, we will mount exhibitions of ancient and contemporary art to give more visibility to the cultures of Africa and of its diasporas.”

Sullivan says that Macron is “making laudable efforts to be on the right side of history in regards to the problem of African cultural, spiritual heritage artefacts held in post-colonial countries”. His client intends to write to the president to enlist his support for the claim, he says.