The exhibition On Documentary Abstraction, now on view at the Art Center/South Florida (until 2 January), sounds, perhaps, like a contradiction in terms. But the New York-based art critic and independent curator Rachael Rakes has brought together four contemporary artists to show the sense of it. The exhibition features work by Torkwase Dyson, Tomashi Jackson, and the Canadian duo Richard Ibghy and Marilou Lemmens, who all practice forms of abstraction to address issues such as history, race and economics.

While researching documentary film and social practice art from the 1990s and early 2000s, Rakes wondered: “What would a non-figurative documentary look like? How do you do that?” As she emphasises in a short essay published to complement the show: “Documentary has never been real, and has, from its beginning, been a form of art.” A truism by now, the fact nevertheless bears repeating, since it opens the door to the possibility for non-pictorial documentary art.

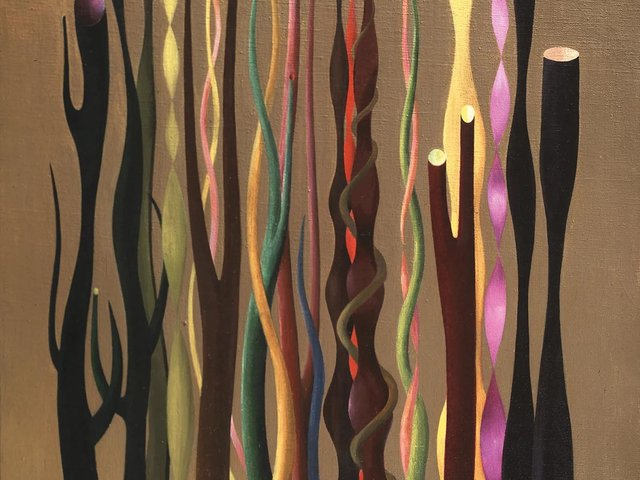

In 2016, Rakes saw “the articulation of what I had been trying to think about” in the work of Dyson. The artist produces immersive black paintings and sculptures that carry within their ravishing surfaces the lasting pain of slavery and racism. She is among a wave of artists today who thwart the sometimes counterproductive tendency to directly illustrate black suffering. “If you obstruct the information and communicate it differently, if you show it differently through spatial abstraction, it might have more of an impact,” Rakes says.

Rakes also explains that the notion that abstraction is somehow inconsistent with social engagement—something that was fiercely debated in the 1960s and 70s during the Civil Rights Movement—derives, in part, from the Modernist critic Clement Greenberg, who famously insisted upon that separation.

“This conceptualisation ultimately ignored centuries of abstract and formalist practices from around the world,” Rakes writes in her essay. “It also disregarded Modern Abstractionists’ own acknowledgement of visual and contextual references outside of their own field.”

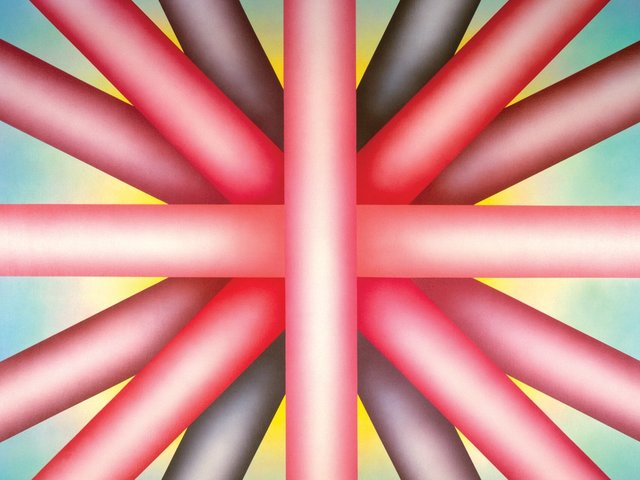

Chewing over these ideas while a fellow at the Art Center earlier this year, Rakes decided to mount an exhibition. In the show, Dyson presents works from her Strange Fruit series of paintings (a reference to Billie Holiday’s song about lynching), which pull from architectural plans. Also in the show, Tomashi Jackson, a Houston, Texas-born artist, has extensively mined the history of abstraction, finding intersections between Josef Albers’s colour theory and race, for example, which inform layered mixed-media works such as Grape Drink Box (Anacostia Los Angeles Topeka McKinney).

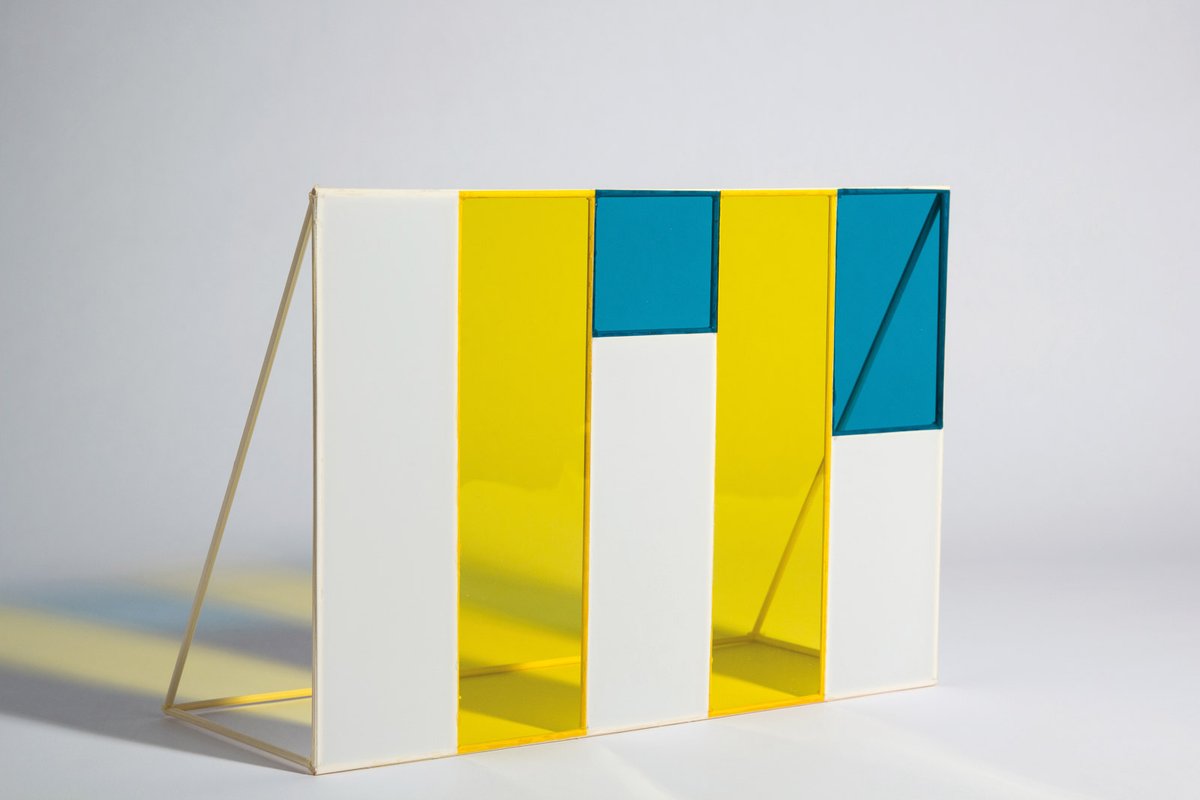

Richard Ibghy and Marilou Lemmens’s 13 sculptures from the series Each Number Equals One Inhalation and One Exhalation are inspired by studies about human productivity from the late 19th century through to the present. These colourful small works translate the schematics and diagrams into materials such as wood, string and plastic. “They’re really obsessed with the dominance of economic thinking in everyday life,” Rakes says. “The idea is that you remove the authority from these graphs by taking them away from their source and making them into sculptures.”

To what degree should curators and artists emphasise the information that supports works like these? It’s a quandary, Rake says. “That’s a tension. It’s not resolved for me and I don’t think it’s resolved for [the artists].” She adds: “I’m OK with someone walking into the show and seeing it because the pieces are striking. The works are beautiful and very colourful. I’m fine with people seeing them on that level or getting really interested in the content as well, or somewhere in-between. I won’t speak for the artists, but I would suspect they are OK with it, too.”

• On Documentary Abstraction, Until 2 January 2018, Art Center/South Florida