“I am the first English abstract artist (not the first female artist) to have made an international reputation,” wrote Paule Vézelay (1892-1984) in 1980. It is a bold claim, but Simon Grant, the curator of the artist’s first dedicated exhibition in over 40 years, points out that a lost 1928 drawing easily pre-dates the shift to abstraction by contemporaries Ben Nicholson, Barbara Hepworth and Henry Moore. “I’ve been wanting to do [an exhibition] for a long time,” Grant says, “it’s long overdue. She’s such an underrated artist in so many ways.”

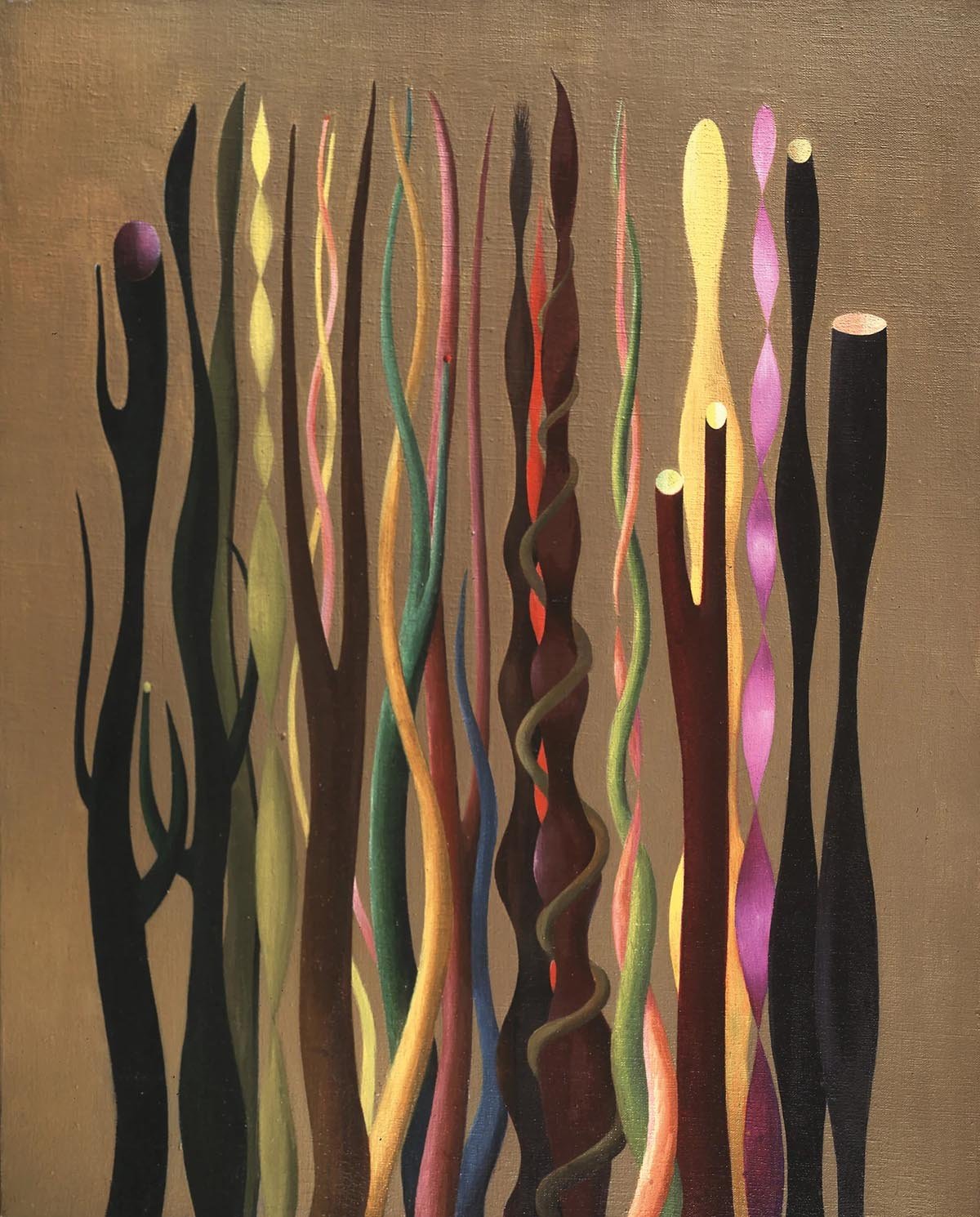

The self-proclaimed “Master of Line” applied herself to sculpture, painting, collage, prints, photography, textiles and more. She was admired by her peers, among them Wassily Kandinsky, Hans Arp and Marlow Moss. Opening this month at the Royal West of England Academy (RWA) in Bristol, Paule Vézelay: Living Lines will include more than 60 works from the artist’s seven-decade career, some of which have never been exhibited before.

Paule Vézelay in her London studio with her 1955 textile Harmony (left) and her 1956 painting The Yellow Circle (right) Photo: Estate of Paule Vézelay

Vézelay was a considerable figure on the international art scene before the Second World War, but her willingness to experiment ultimately worked against her, Grant says: “A bit like Sonia Delaunay and Sophie Taeuber-Arp, she was forgotten because of that dexterity. And yet their dexterity is their strength.”

The Bristol-born artist began life as Marjorie Watson-Williams. “She went against the grain,” Grant says. “Her mother wanted her to be a ‘polished corner’,” but instead she left home aged 20, first for London and then Paris, where in 1926 she changed her name. “English art bored her to tears,” he says. “She found a name that was a little bit ambiguous but sounded non-English.”

She knew she was up against a sea of misogyny and obstruction

A member of the Abstraction-Création association from 1934, by the end of the decade Vézelay had had exhibitions across Europe. She returned to Bristol at the beginning of the Second World War to care for her widowed mother and her brothers, both of whom had suffered shellshock in the First World War. Of this she had previous experience, since the French Surrealist André Masson, her partner from 1929 to 1932, had been similarly injured. “She tolerated hideous abuse,” Grant says. “It comes out in her work of the time—her lines start getting frenetic, edgy. Then she leaves him, and suddenly you have this blossoming of the biomorphic forms, which amazingly, coincided with the whole biomorphic movement in Paris.”

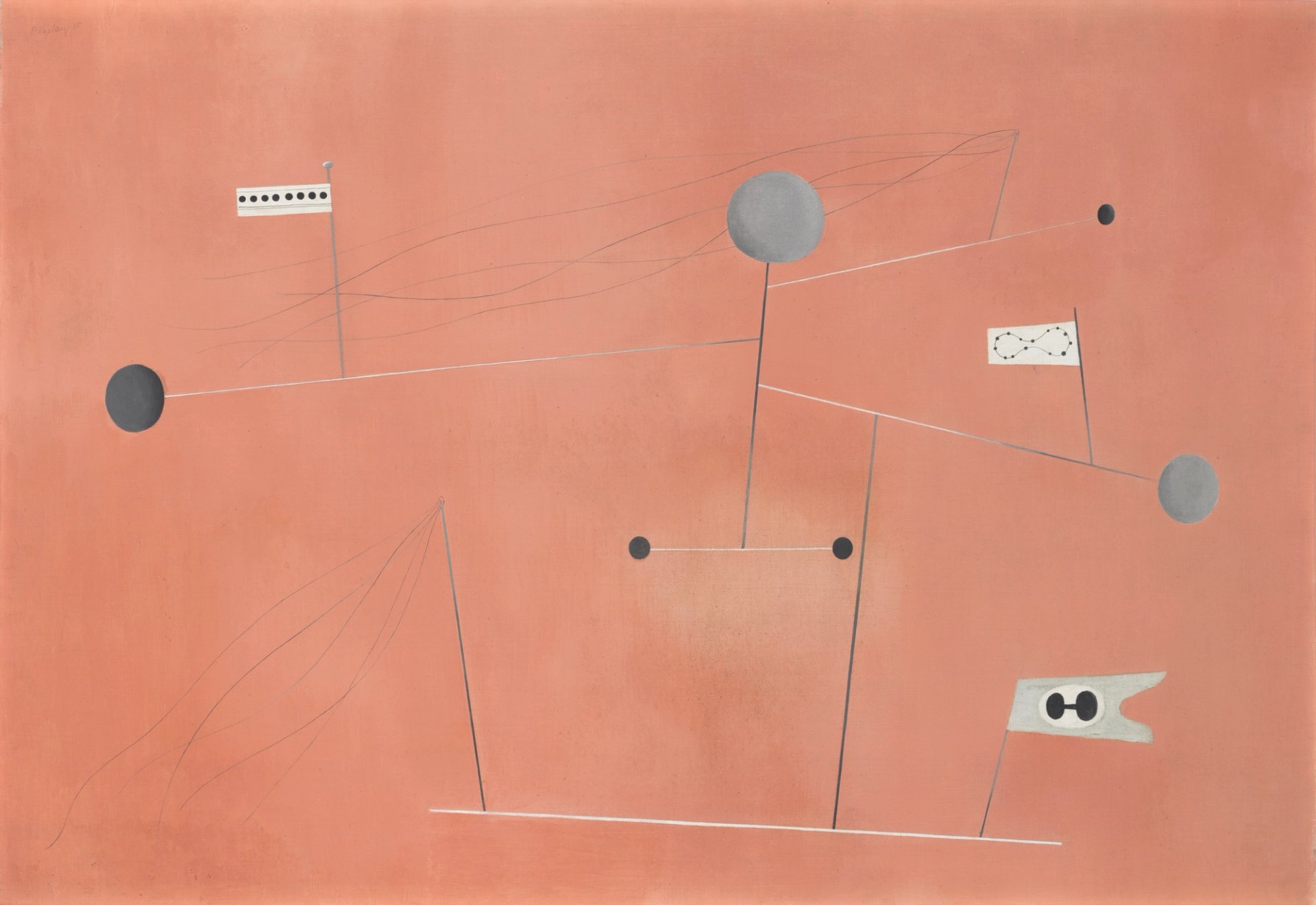

Paule Vézelay‘s Construction. Grey Lines on Pink Ground (1938) © Estate of Paule Vézelay. Photo: Tate

Art was not her only outlet, though. “She’d go fly fishing—it was either that or squash,” Grant says. She began fishing with her father as a child and “whenever he wasn’t catching anything, he’d get out his sketchbook, and you get a sense that her obsession with shadows and silhouettes, which is a really strong theme that runs through the whole exhibition, comes from experiences like seeing a fish moving in a chalk stream.”

Vézelay documented the Bristol Blitz as an official war artist and set up Bristol’s women’s defence corps with the local member of parliament, Mavis Tate. “[Vézelay] was ambitious and canny,” Grant says, “and knew that she was up against a sea of misogyny and obstruction. She was so stubborn and single-minded.”

Despite a major retrospective at the Tate Gallery in 1983, followed by an interview for BBC television with Germaine Greer, recognition eluded her, partly because she was reluctant to be separated from her work, and because she found the business of selling distasteful.

Still, Grant says, “she didn’t seem fearful of any of it. I think she was quite confident about her work. I think it gave her great strength—and joy.”

• Paule Vézelay: Living Lines, Royal West of England Academy, Bristol,

25 January-27 April