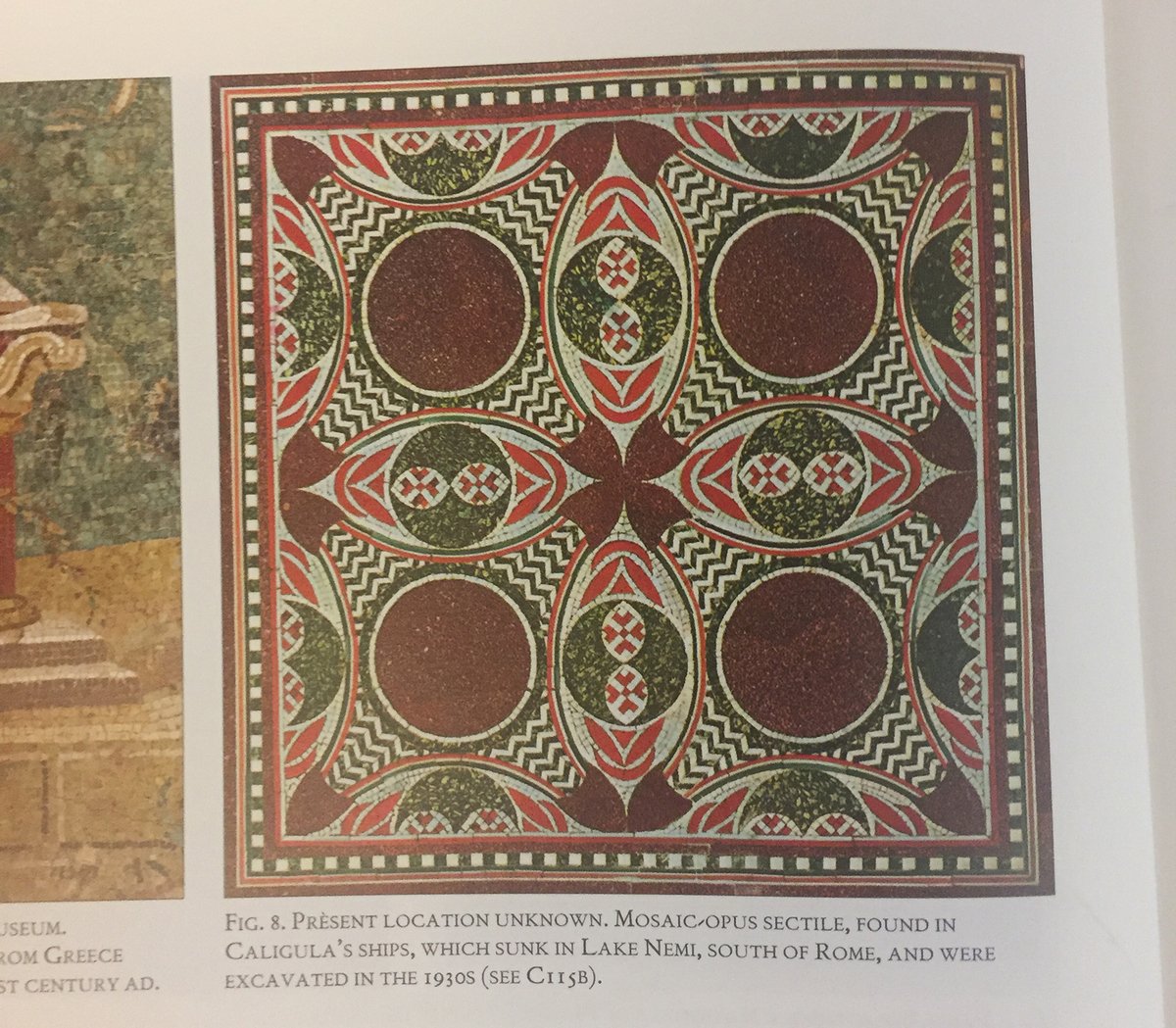

A section of mosaic tile believed to have been commissioned by the Roman Emperor Caligula for one of his massive ships on Lake Nemi was among a group of ancient artefacts returned to Italy on Thursday, 19 October, by the office of the Manhattan District Attorney. Authorities tracked down the work after it was published in a book on porphyry—a reddish purple stone prized by Roman emperors—put out by The Art Newspaper’s founding publisher, Umberto Allemandi & C. The piece was seized in September from the Manhattan apartment of a couple who had been using it as a coffee table, according to the New York Times.

The mosaic, dated to around 35 AD, once decorated the floor of one of three large ships that served as personal refuges for the extravagant emperor, which were sunk after Caligula’s assassination. “His Hellenistic obsession led him to use the great ships of Ptolemy IV Philopater as his model, which were also richly decorated with mixed marbles, including Porphyry,” writes the stone sculpture expert Dario del Bufalo, in his book Red Imperial Porphyry: Power and Religion.

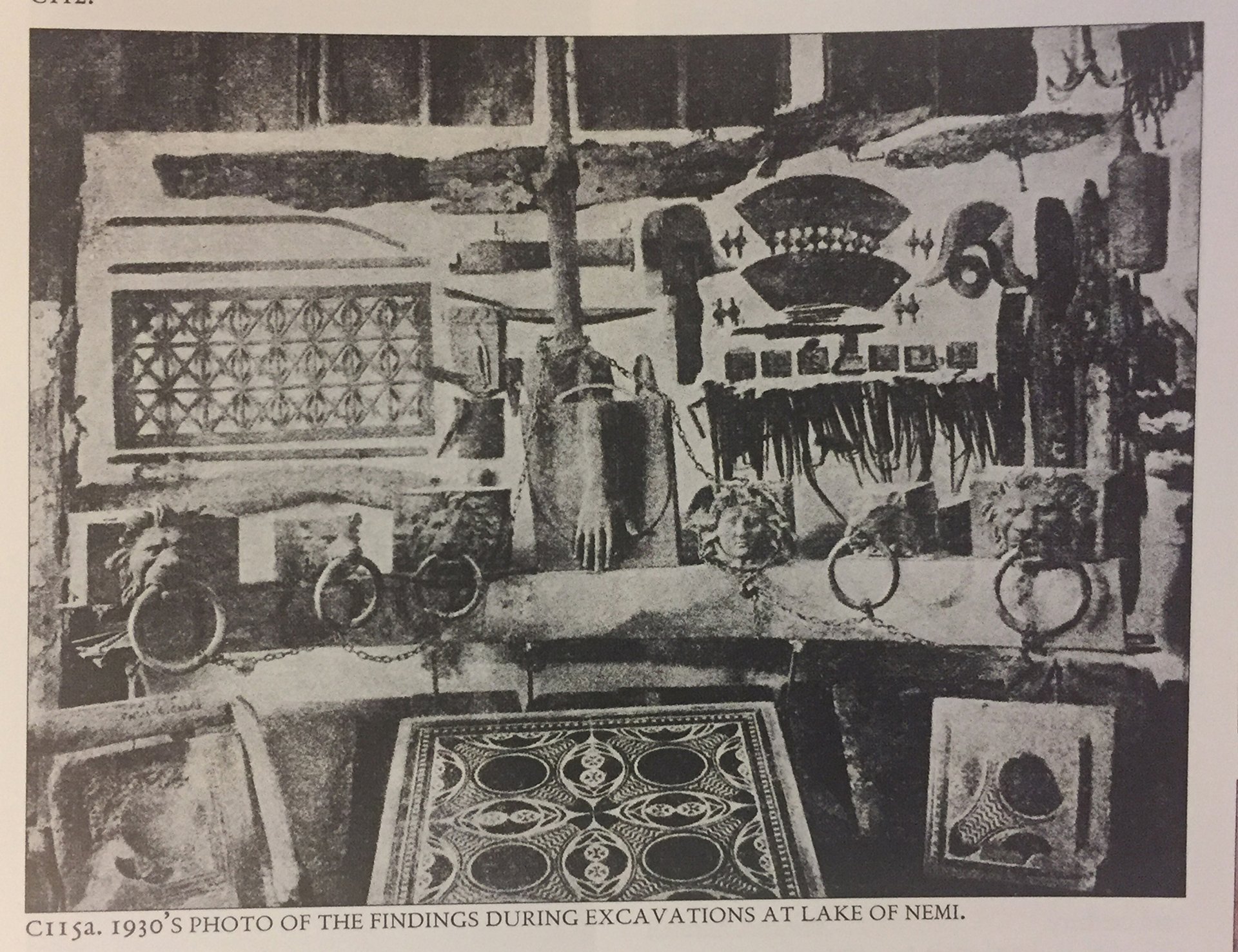

The lake was drained and the ships were excavated under Benito Mussolini in the 1930s and most of the recovered artefacts were housed in a museum built by the Fascist government. “The museum was later used as a bomb shelter during World War II and many of the original tiles were subsequently destroyed or damaged by fire, rendering the mosaic floor piece one of the only known, intact artifacts of its kind,” the district attorney’s office said in a statement. Del Bufalo’s book includes two photographs of the mosaic floor, including one from the 1930s in black and white showing the work along with other object found during the Lake Nemi excavations, and another in colour taken from a gallery in Rome in the 1960s with the caption “present location unknown”.

Umberto Allemandi & C

The effort to track down the work was in part spurred by the New York launch for del Bufalo’s book in October 2013. Eagle-eyed attendees recognised the mosaic as matching one in home of the antiques dealer Helen Fioratti and her husband Nereo, who had mounted it in a marble frame added a pedestal, turning it into a table. Fioratti said they bought the piece in good faith from an aristocratic family in Italy in the 1960s, and the sale was brokered by a police official known for recovering art looted by the Nazis, but they do not have any paperwork for the sale. “It was an innocent purchase. It was our favorite thing and we had it for 45 years,” Fioratti told the New York Times, adding of her decision not to challenge the seizure: “They ought to give me the legion of honour for not fighting it.”

Last week’s restitution also included a red-figure painted terracotta bell krater (around 360-350 BC) that was reportedly looted from Italy in the 1970s and turned over to the district attorney’s office this summer with the cooperation of the Metropolitan Museum, and a Campanian red-figure fish plate (340-320 BC) taken from a Christie’s auction. And earlier this year, the office returned an Etruscan vessel (around 470 BC), stolen from Cerveteri in the mid-1990s, and a group of seven artefacts which were all taken from Manhattan galleries as part of one investigation.