Nadine Hattom, Francis Alÿs et Al

Iraqi pavilion, Palazzo Canalli Franchetti

In an unusual move, the founders of the Ruya Foundation, a Baghdad-based non-governmental body, are pairing ancient artefacts from the Iraq Museum in Baghdad with works by six contemporary artists. The show, with the themes of “water, earth, the hunt, writing, music, conflict and exodus”, is called Archaic.

Tamara Chalabi, Ruya’s co-founder, is organising the pavilion along with Paolo Colombo, who organised the 1999 Istanbul Biennial. They chose 40 objects from the Iraq Museum’s collection, working with basic restrictions such as the prohibition of ivory and other materials. “It’s been a multilayered juggling act,” Chalabi says.

Items include a clay figurine of a fertility goddess from around 5000BC, and a dove-shaped Babylonian weight made of stone. Both were returned to the museum from the Netherlands in 2010, having been plundered following the fall of Saddam Hussein in 2003.

Some of the six participating artists, such as Luay Fadhil and Ali Arkady, live in Iraq, but others are based abroad, including Baghdad-born Sadik Kwaish Alfraji and Nadine Hattom, who live in the Netherlands and Germany respectively. Hattom’s installation, Until the River Winds Ninety Degrees West, features six images from her family album dating from the 1940s to the 1960s. “I’ve removed the people and supplemented them with descriptions of what is happening in the image,” she says. “These are based on memories, mostly from my father… There’s [also] a map, which I’ve turned into a large photo collage using landscape images from the UAE, the sea and mountains.” The map, which documents her family’s migration, is based on an excerpt from an ancient Mandaean holy book, but is “an imagined geography between heaven and earth”.

Chalabi stresses that most of the works have been commissioned. She says: “Alfraji has made work relating to hunting; he refers to old history school books found in Baghdad. It’s very interesting to see Iraq from [the artists’] point of view and how this experience fits with their identity and station in life.”

The Belgian artist Francis Alÿs will also create new works for the pavilion, including 14 paintings and a video, based on his recent experiences with a Kurdish battalion in Mosul, northern Iraq, as part of the military offensive against Isil.

Xavier Veilhan

French pavilion, Giardini

France’s Xavier Veilhan will be in permanent residence for the Biennale’s six-month run. Rather than show his own sculptural practice, he will take the role of “music lover” and host for around 70 invited musicians. The pavilion will become a working recording studio, fitted with obscure electronic instruments such as the ondes martenot and other equipment lent by (among others) Nigel Godrich, the Radiohead producer. The plywood grotto design draws inspiration from Kurt Schwitters’s lost Merzbau, which Veilhan calls a “benchmark” in installation art.

With no stage separating performer from audience, the pavilion will give visitors access to the normally unseen “uncertain moment of creation”, Veilhan says. “When you’re in the studio you can take chances—it’s a place for failure.”

Assisted by the Swiss-American artist Christian Marclay, the Swiss curator Lionel Bovier and three Venetian programmers, Veilhan has put together a line-up reflecting the “rich scene in Venice and the surrounding area”, along with performers as diverse as the French electro star Sébastien Tellier and the Welsh harpist Rhodri Davies. What unites them is “a focus on sound as a raw material”, Veilhan says. The finer details of the programme remain under wraps. “It’s like a blind date,” he jokes. “Maybe on the day you come, there will be a hardcore German saxophonist.”

Carlos Amorales

Mexican pavilion, Arsenale

Carlos Amorales was chosen to represent Mexico in November, against the backdrop of the US presidential election. Donald Trump’s executive orders for a travel ban and a wall on the Mexican border influenced the dark narrative of The Cursed Village, the new animated film at the heart of Amorales’s exhibition. Puppets—of deliberately indeterminate nationality—tell the story of an immigrant family that is violently rejected by a village.

The story is one element in a “total work of art”, says the curator, Pablo León de la Barra. Life in the Folds, the exhibition’s title, refers to the poet Henri Michaux and the “in-betweenness” of Amorales’s multidisciplinary practice, which encompasses graphic design, performance, literature and cinema. For a decade he also managed a record label, Nuevos Ricos, with the Mexican composer Julián Lede.

The pavilion presents music as a “codified language”, Amorales says. He has designed an alphabet of abstract letters based on ocarinas (Aztec whistles) to write poems that double as a music score. Interpreted by the ensemble Liminar, it soundtracks the film, whose characters take on the same graphic forms. There will also be live performances throughout the Biennale.

Geta Bratescu

Romanian pavilion, Giardini and Palazzo Correr

The 91-year-old Geta Bratescu will show old and new works—many unseen outside her native Romania—at the Romanian pavilion in the Giardini and the Romanian Institute of Culture and Humanistic Research in Palazzo Correr. It is not a career survey, but a taster of her wide-ranging works, including drawing, collage, photography, film, installation and writing. The exhibition will touch on recurring themes such as femininity, memory and the studio as a physical and mental space, says the assistant curator Diana Ursan. Though she now rarely leaves her apartment in Bucharest, Brătescu continues to make art daily and without assistants. Among the most recent pieces on show will be geometric paper collages known as the Game of Forms. She calls the process “drawing with scissors”.

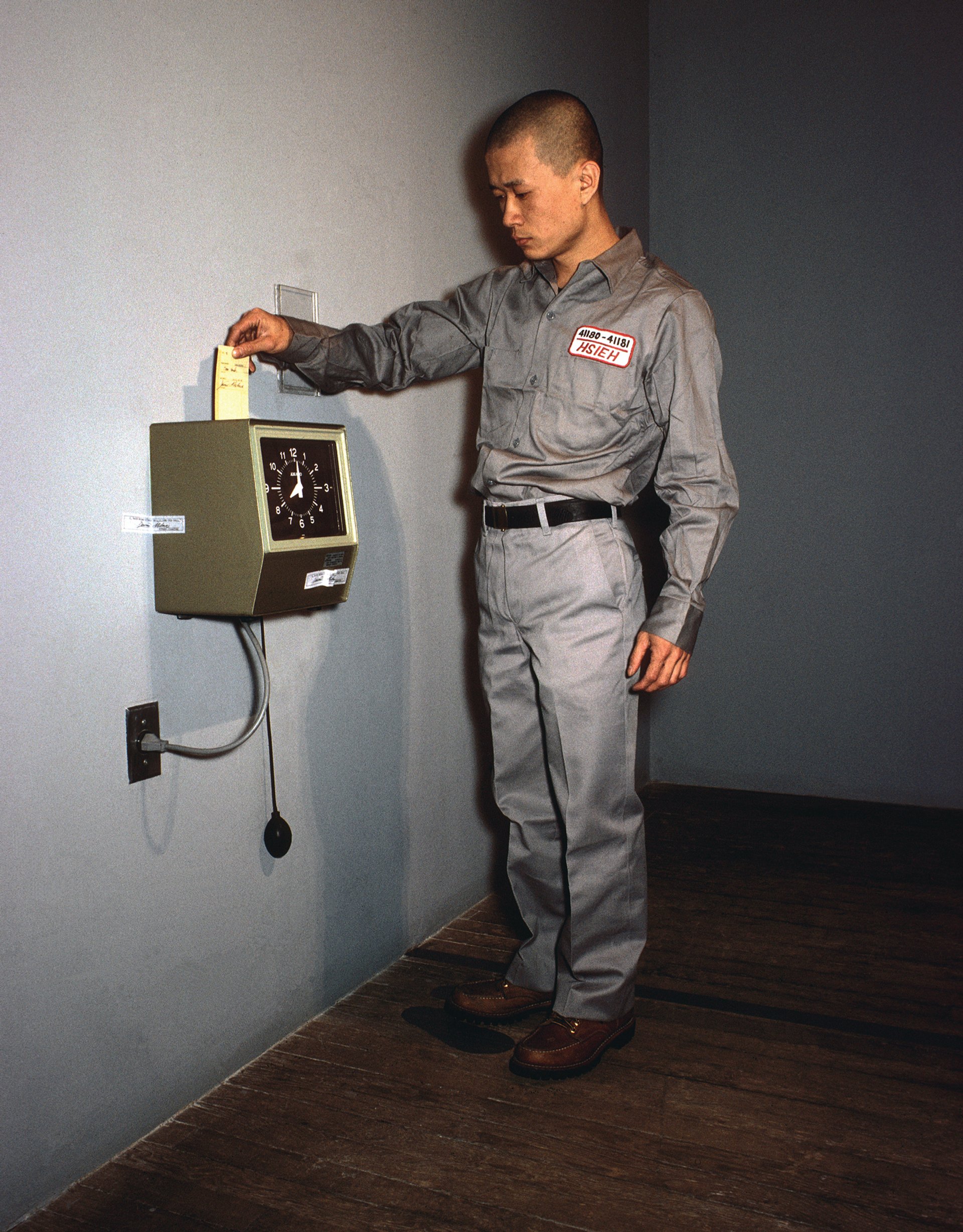

Tehching Hsieh

Taiwanese pavilion, Palazzo delle Prigioni

In late 1970s New York, an illegal immigrant from Taiwan embarked on a series of long-duration performances. With limited English, Tehching Hsieh meticulously recorded the year he spent in solitary confinement in his studio (Cage Piece), the year he went with limited sleep to punch a time clock every hour (Time Clock Piece), and the year he wandered homeless around Manhattan (Outdoor Piece).

Hsieh’s “lifeworks” seem to have been “designed largely for the future”, says Adrian Heathfield, the curator of Doing Time, his exhibition in the Taiwanese pavilion. “If he hadn’t documented them, perhaps he wouldn’t have been believed.” Photographs, films and objects from two of the performances will be on view in the most extensive show of Hsieh’s work to date. The works reveal Hsieh’s prescient commentary on the capitalist condition and the statelessness of migrants, according to Heathfield.

A room will focus on previously unseen early works made before he left Taiwan, including his brutal first performance, Jump Piece (1973)—a fall from a second-storey window that broke both his ankles.

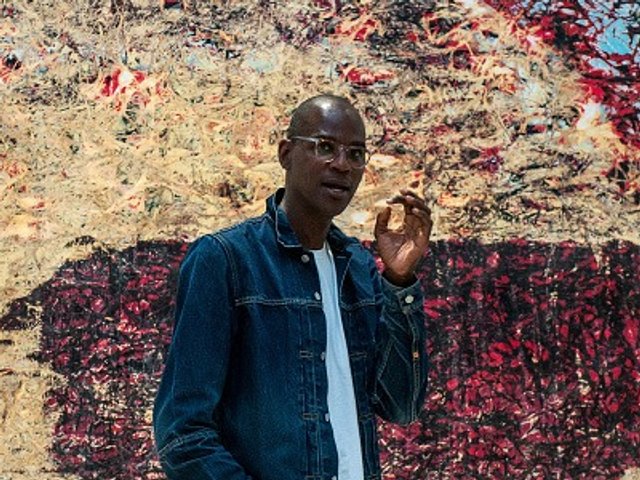

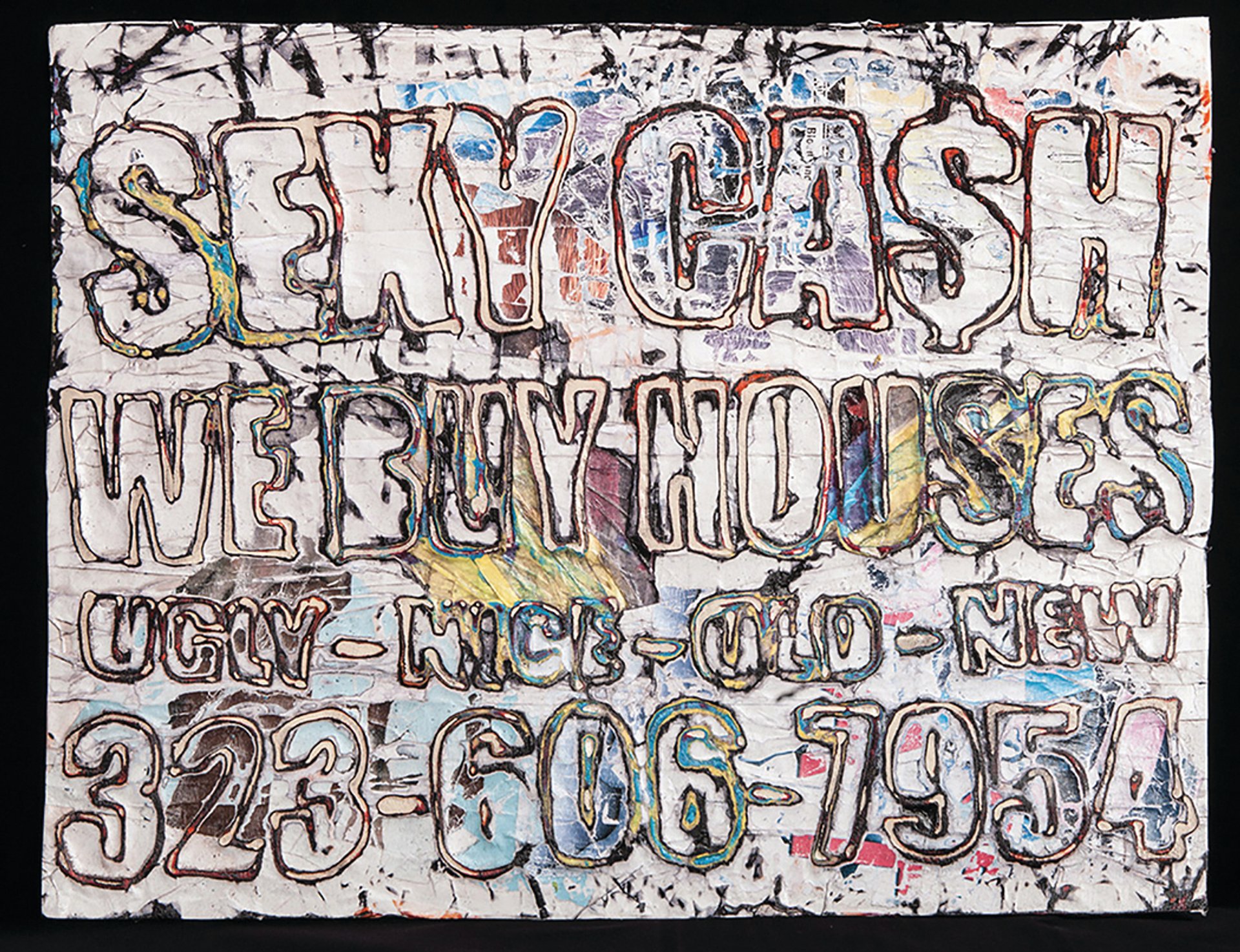

Mark Bradford

US pavilion, Giardini

The art and vision of Mark Bradford, the Los Angeles-based artist in the US pavilion, could not be more pertinent, says Katy Siegel, the research curator at the Rose Art Museum at Brandeis University. “The pavilion opens with Donald Trump in office, at a moment of enormous uncertainty and social crisis, and Mark’s work, his understanding of social life in the US, and his direct action with regard to social need are more relevant than ever,” she says.

Bradford opened a shop in April in the Frari district of Venice, where prisoners make and sell products, run in partnership with a local co-operative dedicated to finding employment for people serving prison sentences. “What Mark has personally experienced has helped to make him deeply insightful about the American landscape, about the collapsing centre and the massing periphery,” says Siegel, who is co-curating the exhibition, entitled Tomorrow Is Another Day, with Christopher Bedford, the director of the Baltimore Museum of Art.

These social preoccupations spill over into his abstract and collage-based works. Earlier this year, Bradford unveiled a circular fresco of works at the Hirshhorn in Washington, DC (until 12 November 2018), based on Paul Philippoteaux’s 1883 cyclorama depicting the climax of the Battle of Gettysburg.

Although the exact nature of his Venice work is under wraps, the pavilion website stresses that Bradford will be more strident than ever in his presentation, renewing the “tradition of abstract and materialist painting”. It adds that “the cyclical threat and hope of American unfulfilled social promise” is the artist’s priority.

Asked if there will be any departures, Siegel says: “Some of the surprises are—counterintuitively—returns; others are entirely new artistic experiments.” And has the experience been exciting and daunting? “It was a wild ride. We started in one place, with train travel and Gone with the Wind, and ended up somewhere very different.”

Anne Imhof

German pavilion, Giardini

Anne Imhof, this year’s Germany representative, shot to critical acclaim after winning the Preis der Nationalgalerie in 2015 and subsequently producing the immersive three-part opera Angst in Basel, Hamburg and Montréal. The pavilion’s curator, Susanne Pfeffer, the director of the Fridericianum in Kassel, says she chose Imhof because she confronts the “rapid and fundamental political, social, economic, pharmaceutical and technological changes that we are currently facing” with “a hard realism”. She adds: “Imhof makes this transformation visible through the use of the body, showing how much our bodies are part of power structures, capitalism and biopolitics.”

Imhof’s show will include continuous performance elements that will change and accumulate over time. Visitors can expect some of the notable components of past performances, such as live animals and technology. Imhof has been working with collaborators from the fields of philosophy, painting, music and law, and their different personalities are worked into the performances. The show will include paintings, sculpture, installations and seven new musical compositions that work with the pavilion’s space and architecture.

Egill Sæbjörnsson

Icelandic pavilion, Spazio Punch

Apparently, 54% of Icelanders believe in fairies, so it’s no surprise that this year’s Icelandic pavilion has been taken over by two trolls. The fictional characters Ugh and Boogar are the artistic companions of Egill Sæbjörnsson, an artist and musician. Called Out of Controll, and organised by Stefanie Böttcher, the director of Kunsthalle Mainz, works supposedly made by the 36m-tall trolls will be on show.

Björg Stefánsdóttir, the director of the Icelandic Art Center in Reykjavik, which has commissioned the 2017 pavilion, says the show is part of the Icelandic pavilion’s tradition for “dissolving social constructs, whether they be ideologies, nationalist sentiments or the myth of the artist”. The final choice of pieces for the Biennale was decided at the last minute, but the new large-scale works (“big fingers make it difficult to make small things,” says Sæbjörnsson) include paintings, ceramics, concrete and cement statues, found objects and chocolate sculptures. Sæbjörnsson has created a new musical composition and produced a book to accompany the show. The trolls are also breaking out into the digital sphere—they’re crowdfunding to create their own perfume; you can follow them on Instagram using the @icelandicpavilion handle and the hashtag #outofcontroll.

Cevdet Erek

Turkish pavilion, Arsenale

The Turkish pavilion’s artist this year is no stranger to biennials. In the last five years, Cevdet Erek, who works predominantly with sound, space and rhythm, has taken part in Documenta and in biennials in Sharjah, Marrakech, Istanbul and Sydney. He is best known for his ongoing series Room of Rhythms, where he uses site-specific sound installations to occupy often empty spaces and tell their hidden stories.

The exhibition for the Venice Biennale is called ÇIN—an onomatopoeic Turkish word for a metallic bell sound, the reverberation in an architectural space and also the effects of tinnitus. The first research trip the artist took to Venice was a few weeks before the attempted coup in Turkey in July 2016, which played a part in his early research. “Turkey and around was on fire. Fight, death, migration—it still keeps on in continuing and new scenes,” says Erek. He describes the work as an architectural intervention with sounds—“a temporary reuse for a ruin that is remade and kept in good shape”. He adds that the pavilion’s position in between those belonging to far-away countries, such as Peru, South Africa and Singapore, became a defining factor for the spatial design of the exhibition.

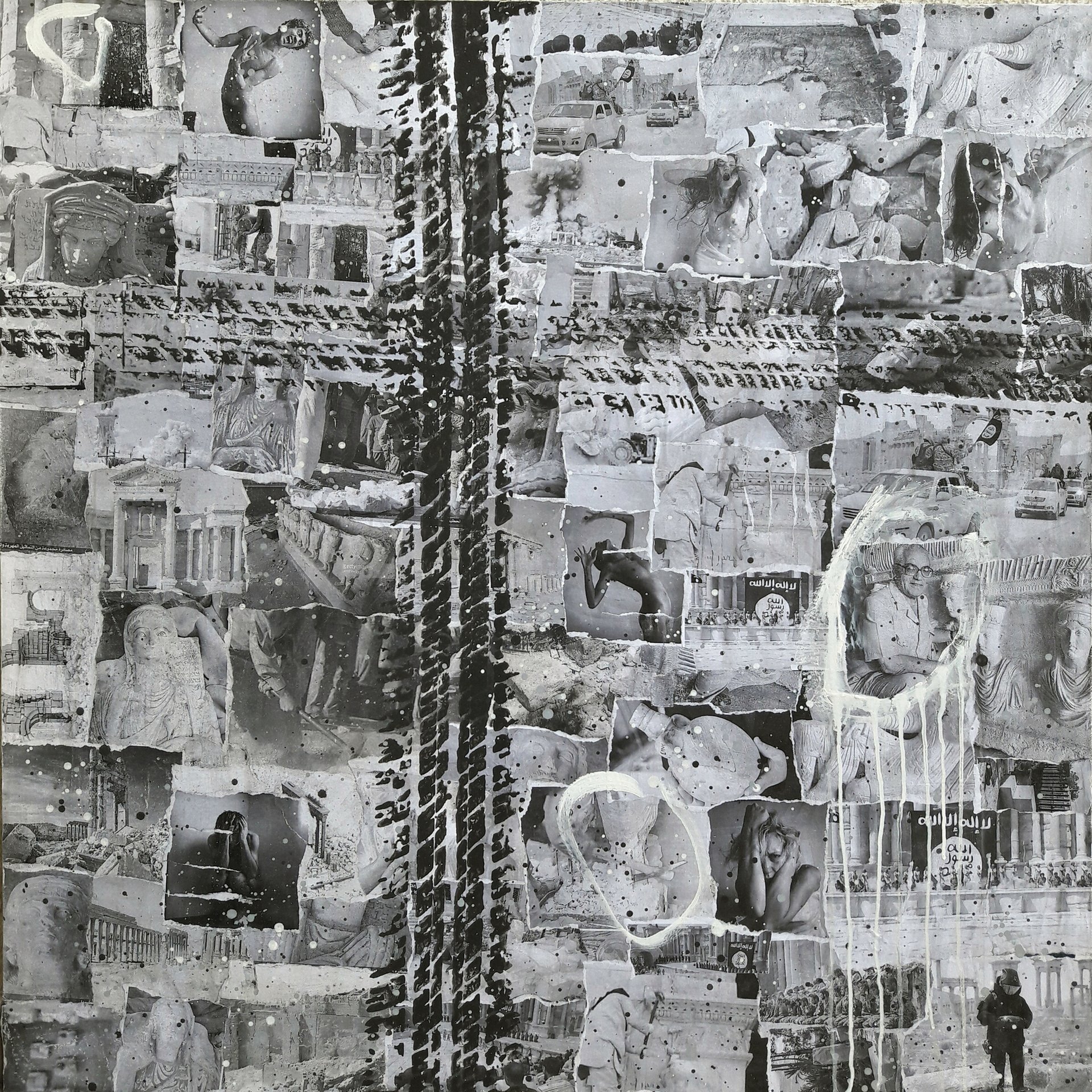

From Palmyra?

Syrian pavilion

Ex Cinema Chiesa del Redentore

Embroiled in a civil war, it may seem surprising that Syria has a national pavilion at the Biennale. Its past pavilions have often seemed more Italian than Syrian, having been commissioned and curated by an Italian art publisher since 2009 and with Italian artists featuring heavily. Emad Kashout, a cultural official in Damascus, has curated and commissioned this year’s show, but half of the eight artists are Italian and none of them is well known.

Mouna Atassi, the founder of the Syrian Atassi Foundation for Arts and Culture, says the pavilion’s problems are deep-rooted and involve an outdated approach to supporting art in Syria. “Art and culture have been monopolised by the authorities for over 40 years, with absolutely no role for the private sector. This leaves the authorities with too big a task,” she says. She also cites the major shortage of Syrian curators, critics, publications and institutions as an issue in creating a successful pavilion.

This year’s exhibition Everybody Admires Palmyra’s Greatness is heralded as a tribute to the ancient city that has become a contested site in the civil war. According to the press release, in the spirit of the legacy of the heritage site, “each artist, in his own way, will be asked to attest the importance of leaving prints and evidence of human passage in human existence”. Atassi adds: “Unfortunately we cannot say that we have ever been proud of the Syrian pavilion at Venice. Our view is that one should either present a pavilion worthy of the country—or forget it all together.” The pavilion’s press team could not be reached for comment.