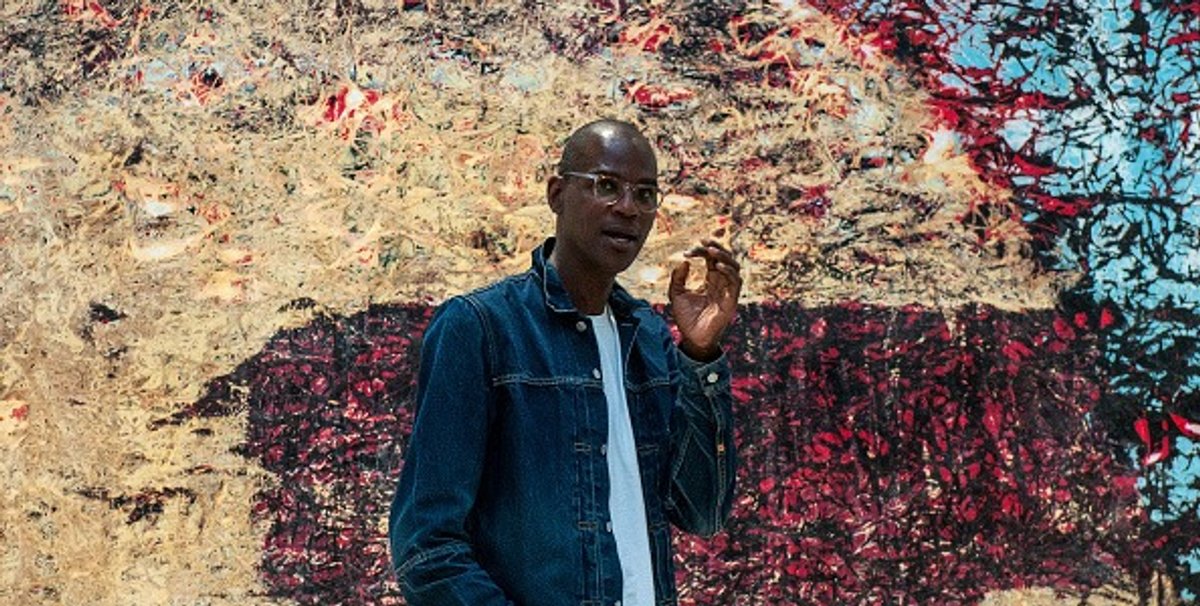

The Los Angeles-based artist, Mark Bradford, who is the toast of the Venice Biennale for his US pavilion, delivered on Thursday (11 May) a masterclass in making the art world part of the real world. He said that if you want to work with people facing real hardship, you really have to "listen and be prepared to write the check" for what "they want", with the stress on the word "they". Puncturing pretensions, he criticised those seeking a “photo-op” at others’ expense. Bradford was speaking at an event organised during the Biennale’s preview week by Pamela Joyner, a leading US philanthropist and collector of his work, and other African-American abstractionists.

The talk was moderated by Katy Siegel, the co-curator of Bradford’s exhibition, Tomorrow is Another Day, which turns the ideologically loaded space of the neo-classical US pavilion on its head. Forget ivory tower, or Camelot, think grotto and Greek myths meets the scrappy street life of South Los Angeles.

Back home in America, Bradford’s activism includes Art + Practice, a project he co-founded, which provides access to art and support to young people in foster care among others in his local community. Meanwhile, in Venice he has backed a shop where prisoners can sell the products they make in partnership with a local co-operative, Rio Terà dei Pensieri. It will stay open long after the Biennale closes in November—Process Collettivo is a six-year project—as the artist has invested in it for the long-term. Institutions have a responsibility to put others’ needs first he said, particularly when working with local communities “used to being exploited”.

Another leading artist, the Mexico-based, Belgian artist Francis Alys, is showing paintings, drawings and a film produced on the front line in Mosul last year at the Iraq pavilion in the Palazzo Cavalli-Franchetti. Alys spent time meeting refugees of the conflict as well documenting a Kurdish battalion’s campaign to liberate Iraq’s second city from Isis. Why take on the role of a war artist? This war is “medieval barbarism perpetrated and spread with the most modern of technologies”, Alys recently told Artforum. The Baghdad-based Ruya Foundation, the pavilion commissioner, also invited Alys on a research trip last year to refugee camps in northern Iraq where he held a series of workshops.

Numerous national pavilions, works of art in Viva Arte Viva, the main show of the 57th Venice Biennale and its collateral exhibitions aim to raise awareness about people facing hardship and exploitation. In a contentious move, the Tunisian pavilion (The Absence of Paths) is issuing “freesas”—fictional travel documents permitting freedom of movement worldwide—at three kiosks around the city.

The freesa document points out that the current humanitarian crisis stemming from forced migration across the Middle East and beyond underpins the project. The imitation visas are issued by “aspirational [Tunisian] migrants”, nationals who are expected to return home after the Biennale ends.

There are, meanwhile, around 40 refugees, living in Mestre on the mainland near Venice, who are taking part in Studio Olafur Eliasson and TBA-21’s Green Light project in the Central Pavilion in the Giardini. The initiative is led by the Danish-Icelandic artist who has designed a special lamp for Venice on sale at €250 each (proceeds go towards the project). “It takes two people to create a lamp,” Eliasson told us, stressing that the creative process involves both visitors and refugees who cooperate in making the lamps, getting to know each other a little better.

This is the Biennale that wears its social responsibility on its sleeve, literally. The tote bag to be seen with is printed with the slogan: “Refugee Rights” and on the reverse: “Indigenous Rights”, spreading the message that the Australian artist Tracey Moffatt’s pavilion, My Horizon, refers to both. For Vigil (2017), Moffatt has spliced together shocking photographs of migrants in distress at sea with stills of Hollywood stars’ faces frozen in horror.

The US-Taiwanese artist Tehching Hsieh is living proof of how a country’s art can benefit from a migrant artist. Hsieh arrived in New York in the late 1970s as an illegal immigrant. As “Sam Hsieh”, the young artist created epic durational performances, such as Manhattan (Outdoor Piece, 1981-82). In Venice, he shows photographs and ephemera documenting the year he wandered homeless around New York. The show includes an installation documenting another year-long performance. For (Time Clock Piece, 1980-81), the artist spent 365 days with limited sleep, punching a time clock every hour. The curator of the Taiwanese pavilion Doing Time Adrian Heathfield, tells us that “Hsieh’s work is a prescient commentary on the statelessness of migrants”.