“Everything seems to indicate that the past is not preserved but is reconstructed on the basis of the present,” the French sociologist Maurice Halbwachs wrote in Les Cadres Sociaux de la Mémoire (The Social Frameworks of Memory) in 1925. Cultural Memories in the Roman Empire, a collection of conference papers presented in 2013 at the Getty Institute, edited by Karl Galinsky and Kenneth Lapatin, aims to extend Halbwachs’s thesis—how did the Romans and their subjects use the present to interpret and to construct the past? The book is the latest contribution to memory studies, the research field that developed out of Halbwachs’s pioneering work on collective memory. It is the second of three volumes to appear as part of Memoria Romana, a research project funded by the Max Planck Institute. All the contributions to this book are, however, by anglophone academics.

The 14 essays presented encompass art and architecture from the third century BC to the fourth century AD and range geographically from Greece to Britain and from Roman Asia to Spain. The first chapter lays out the conceptual frame of reference, but the substance of the book is in those chapters that focus on local history, identity and power. Among them, Carlos Noreña argues that Hellenistic ruler cults in the late Roman Empire were used to foster a sense of local patriotism that served the Roman policy of divide et impera (divide and rule)—the encouragement of rivalry to frustrate attempts to form anti-Roman coalitions.

Brian Rose also offers an interesting insight into the Roman practice of “memory-shaping” in the provinces, examining the Julio-Claudian efforts to elide images of the dynasty with Troy’s heroic past. Following Augustus’s strong economic support for the Troad peninsula where Troy, or Ilion, had stood, a strong relationship between his dynasty and Ilion developed. Imperial statues at Ilion—80% of which represented Julio-Claudians—bore the inscription “kinsman”, to mark the supposed Trojan ancestry of the Roman rulers, the descendants of Aeneas. Despite the fact that the inhabitants of the region were at that time Greek, a consanguineous relationship with the Romans was artificially created.

Elizabeth Marlowe focuses on the Vicennalia Monument, a marble block now standing on Rome’s Via Sacra and part of the Five-Column Monument set up in the Forum to celebrate tetrarchy—the joint leadership of the empire by four men instituted by Diocletian and his successors. Marlowe proposes that sites of memory are created when one party has something to lose and another something to gain in the depiction of the past.

The Vicennalia Monument attempts a visual compromise between the old power and values of the Senate and the legitimation of the new tetrarchical political order.

The four emperors are depicted not as military leaders fighting at the empire’s borders, but as Roman citizens wearing the toga, with the ritual sacrificial instruments rendered in minute detail as a tribute to the old religion. The whole depiction echoed the Ara Pacis—Augustus’s altar of peace, which was the strongest visual symbol of the old imperial power.

The essays that form this book do not focus on the appropriation of a single past, but rather on a variety of places, memories and therefore identities. This type of approach proves most effective when it studies the way in which historical developments modified the past and shaped a new identity that manifested itself in art and architecture. However, some essays eschew specificity and waft off into ethereal theories and cultural concepts, using material culture as rhetorical decoration.

Halbwachs offered an idea about how history could be studied, but memory studies have gone beyond this to become an independent research field. In her introductory essay Susan Alcock, one of the pioneers in the field, compares the undertaking to a kaleidoscope. This metaphor could describe this book: not a lens or filter, but the Roman world in all its variegated aspects.

• Maddalena Alvi studied classics, history and art history at Bern University and at Christie’s Education in London. She has worked as a curator at Sam Fogg Gallery and as a researcher at the University of Bern, the State Hermitage Museum in St Petersburg and the Rothschild Archive

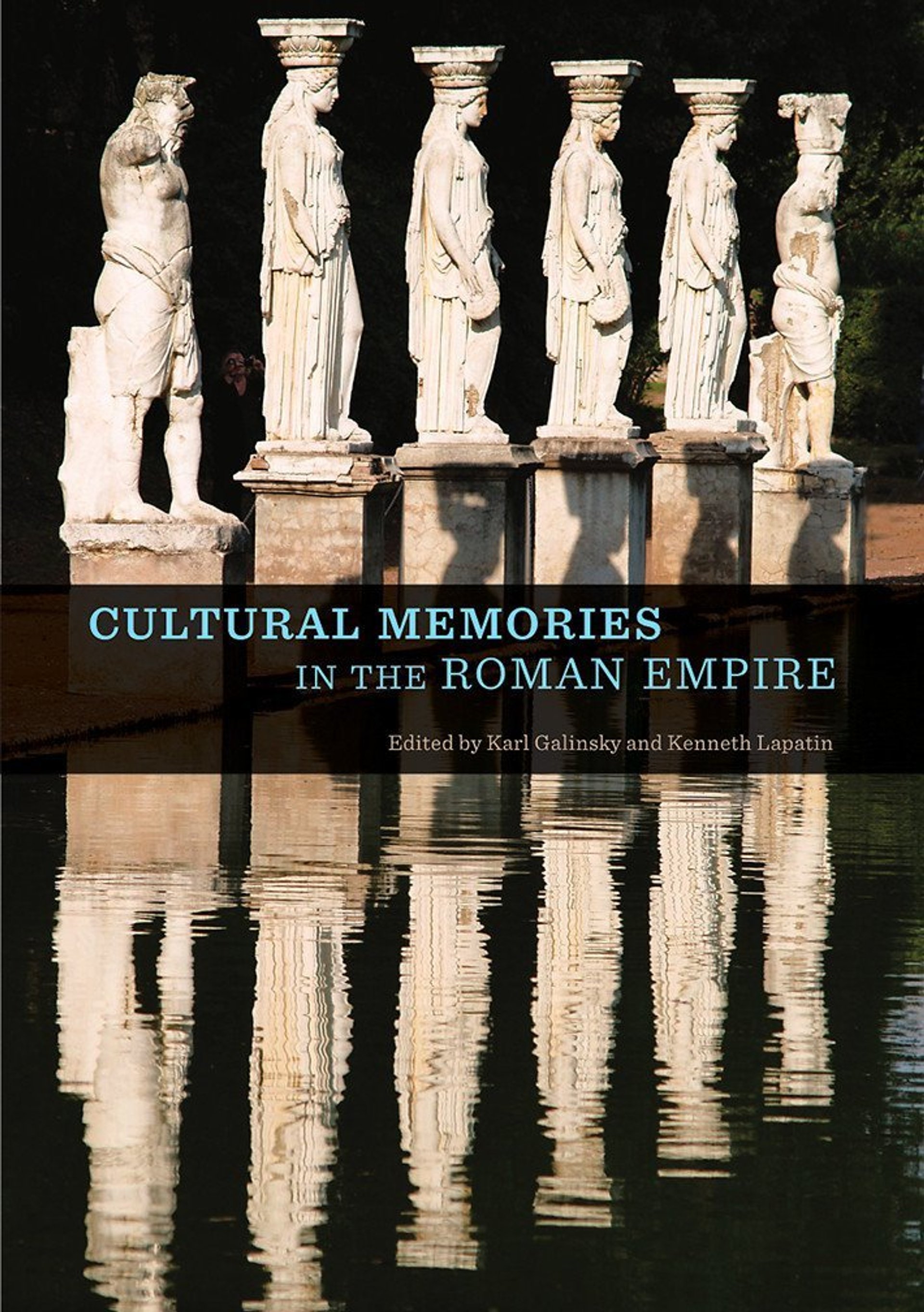

Cultural Memories in the Roman Empire

Karl Galinsky and Kenneth Lapatin, eds

Getty Publications, 376pp, $85 (pb)