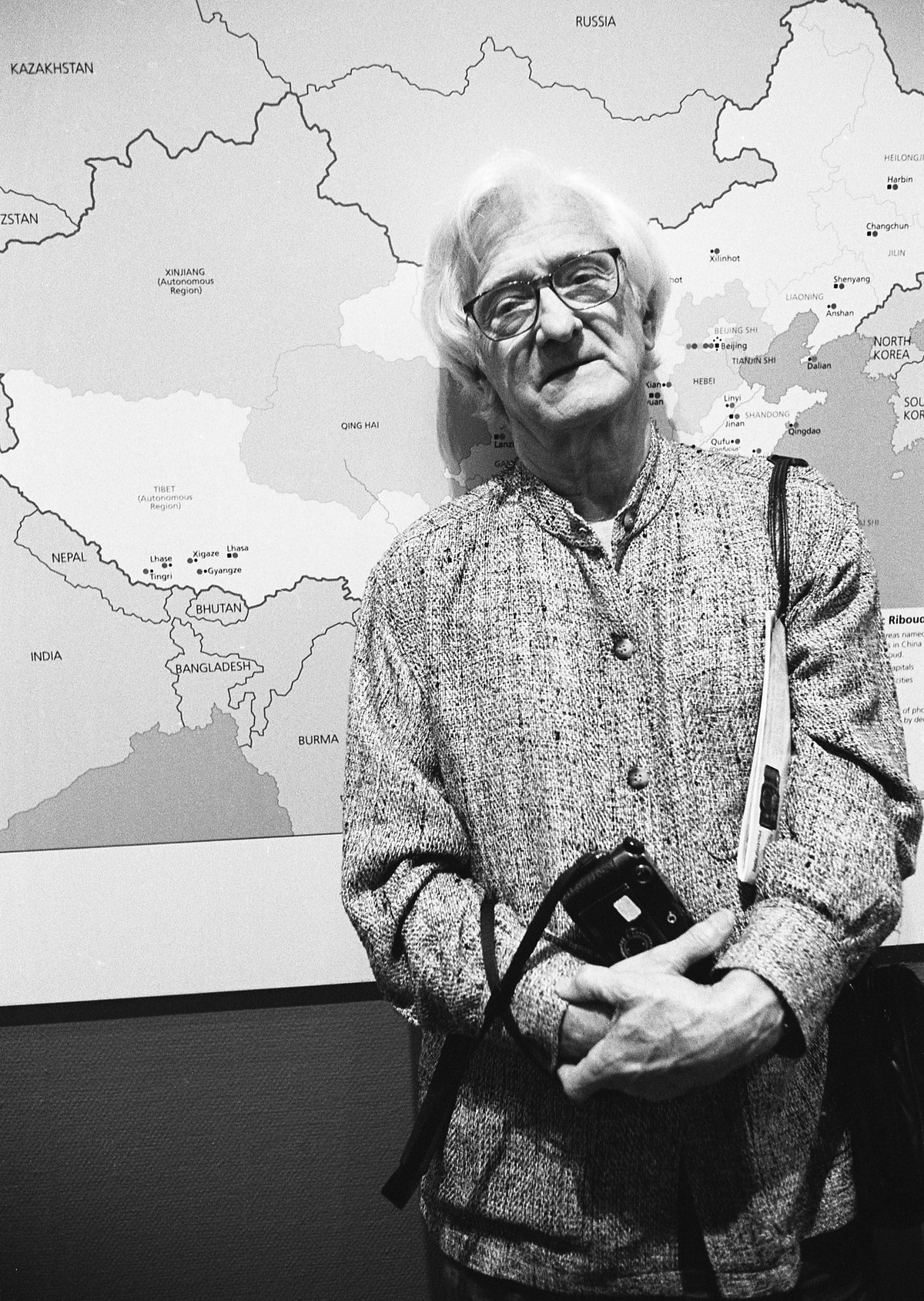

In order to take the pulse of a culture or a society, it is necessary to invest time an extended period of time, to feel and photograph the ebb and flow of events. This was the pattern of Marc Riboud's existence from the mid-1950s until the end of the last decade, when illness prevented him from traversing the world in a long series of photographic "rambles". He died on 30 August.

Such a "humanist" approach involves patient recording of the rhythms of everyday life, and is potentially more revealing of its subjects than celebrity portraits or shock news pictures. One of Riboud's most widely known photoraphs is an iconic visualization of the anti-Vietnam war movement: a young woman offering a flower to ranks of bayonet-wielding national guardsmen during a demonstration in Washington in 1967. The last frame on the last film Riboud had in his camera that day, it symbolises his lifelong obsession "with photographing life at its most intense, as intensely as possible".

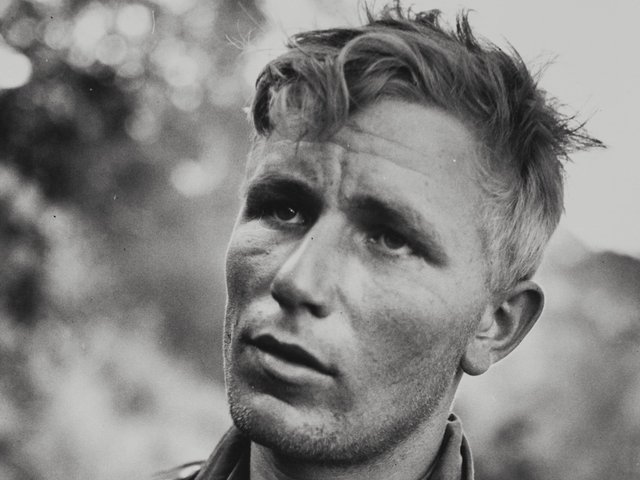

His family background promised another sort of life. Riboud was born into a wealthy upper-middle class family on 24 June 1923. His father Camille was a banker and industrialist with humanist sympathies in Lyons, France's second city, and the father of seven children, of whom Marc was fifth in line. As a child he had great trouble in expressing himself and was very shy. Riboud père tried hard to impel his son in the right direction. He even gave him the Vest-pocket Kodak that he had carried through the trenches during the 1914-18 war, with the words "although you might not know how to express yourself, perhaps you will learn how to look at things". Young Marc was only 14 at the time but set out to photograph the chateaux of the Loire, then the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1937, where the pavilions of the totalitarian regimes—Nazi Germany, Soviet Russia and Fascist Italy—glowered at each other across the Seine.

His father committed suicide in November 1939 in despair at the outbreak of a new world war, but he bequeathed Marc his Leica camera. It was to become the symbol of his profession. Yet Riboud remained shy and found it difficult to photograph people, and it was not until well after the war (during which he had been active with his brothers in the Resistance movement) that he decided to leave the comfortable vocation of engineer in Lyons in 1951 to try the new and somewhat disreputable job of freelance photo-journalist in Paris. His brother Paul had married a Cartier-Bresson sister and Marc was introduced to the "great Henri" himself who was impressed by his images, saying: "you were born with a keen eye". They exchanged ideas though the older photographer proved domineering. Riboud later admitted: "You'd have to be a saint to live with him—but his advice was inspirational, and listening to him talk about painting, politics, literature was fascinating." These were the very early days of the Magnum photo agency. Whilst one founder, Cartier-Bresson, was a great source of cultural information and advised Riboud which museums and art galleries to visit, another founder, Robert Capa, told him to learn English and fixed up his first assignment, to photograph a painter working on the Eiffel Tour in balletic pose. Riboud sold the pictures to Life magazine in 1953, which made his name.

A year spent in London in 1954 produced wonderful images of street games and crowds, though marked by a certain distance between photographer and subjects, so he decided to tackle his shyness by seeking more exotic locations. George Rodger, another of Magnum's founders, sold him a specially equipped Land-Rover, which Riboud drove overland to Calcutta. After almost a year photographing in India, the urge to go further east proved strong, and on the last day of 1956 he crossed the border into China at Hong Kong, one of the first western reporters to be allowed into the country since the communist revolution of 1949. He would also visit the Soviet Union, and both South and North Vietnam during the conflicts on the 1960s and 1970s, as well as Castro's Cuba during the missile crisis and Bay of Pigs era.

Riboud's work in China and elsewhere is marked by a sense of humility in front of his subjects. As he noted "a camera is easy to use, but proper use of the eyes requires a long, long apprenticeship often capped with great pleasure". His photograhs became the notebook in which he recorded his passage through life, intimate records of a personal encounter with the places and societies he visited. "I am not an analyst," he said. "I just collect impressions". During his trips to China, Riboud photographed important political leaders like Mao and Zhou en Lai, but his photographs portray them as ordinary people—they neither lionise nor condemn. He believed that "photography must not try to be persuasive. It cannot change the world, but it can show the world, especially when it is changing."